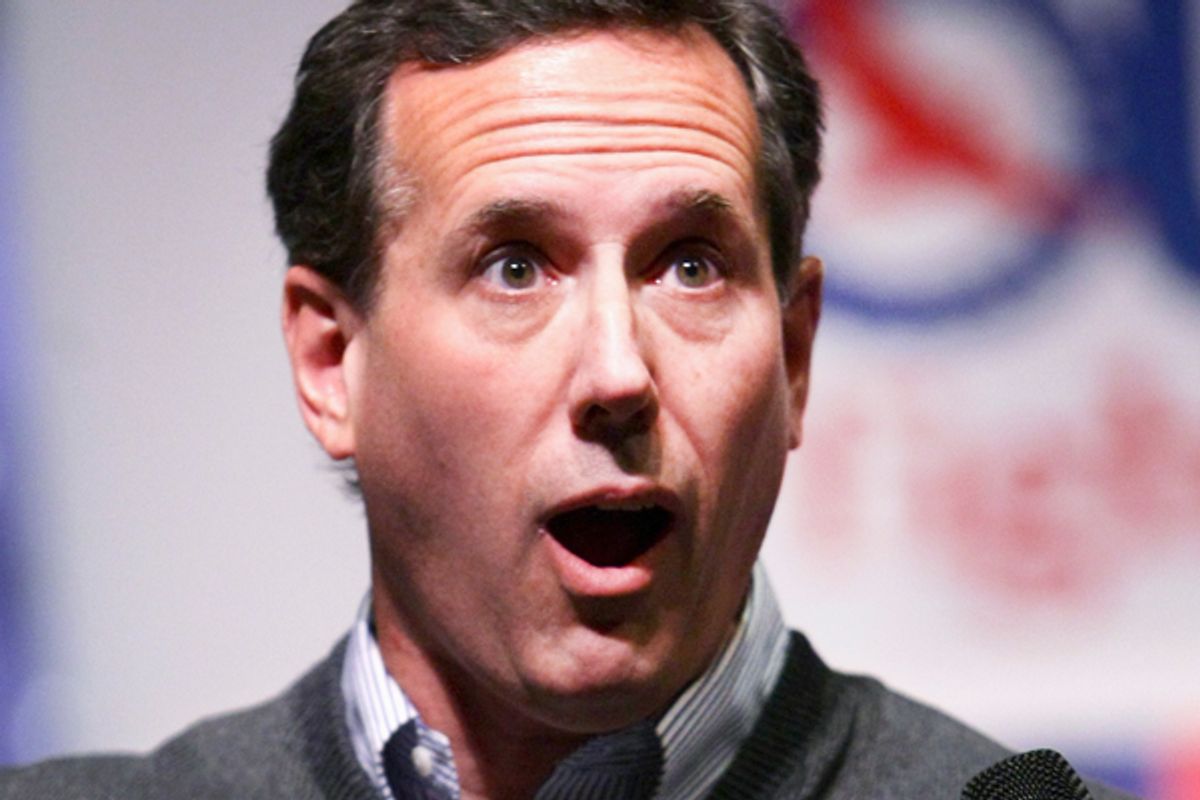

When he unexpectedly emerged as Mitt Romney's chief foe, Rick Santorum posed a unique challenge for the former Massachusetts governor, who had previously deflected one conservative insurgency after another.

Unlike Rick Perry, Herman Cain and Newt Gingrich, Santorum appeared to be an essentially competent candidate -- no immediately disqualifying personal or ethical baggage, issue positions that put him in line with the party base, and solid communication skills. And Romney, because of the suspicion with which conservatives regard his own ideological credentials, was hardly in a position to make the most logical argument against Santorum: that his history of addressing hot-button social issues in indelicate ways would make him a ripe target for Democrats in the fall.

This is what made Santorum's initial pledge not to make social issues the focus of his Michigan campaign a serious problem for Romney. Conservatives who vote on cultural issues already didn't trust Romney and already knew that Santorum was one of their own. So by playing up his economic message (and his own middle-class identity), Santorum would have a chance to make Romney's problem with blue-collar and middle-class voters worse while expanding his own base and showing party leaders that he's more than a niche candidate and that they needn't fear nominating him.

Instead, just about every headline that Santorum has generated since then has been about culture war politics, a trend that has accelerated in the past few days as he's blasted Barack Obama's "phony theology," railed against mandatory coverage of prenatal care, and even made a Hitler reference. There's also the stir that one of his aides caused on Monday by warning on national television about Obama's "radical Islamic policies." (She meant to say "environmental policies," the aide claimed.) And these are just the highlights.

I previously theorized that Santorum might be doing this because he's worried about anti-Romney evangelical voters -- particularly in the South -- voting for Newt Gingrich, whose candidacy was just tossed another lifeline by Sheldon Adelson, and splitting the conservative base. Or maybe he's just doing it because he's Rick Santorum and he can't help himself. Whatever the explanation, his refusal to rein himself in after his "phony theology" remarks first attracted notice is drowning out whatever he has to say about economic issues and reinforcing his image as a culture warrior politician.

This poses two problems for him. One is that the negative tone of the headlines he's generating -- at one point Monday, the top of the Drudge Report was monopolized by links about Santorum controversies -- could be alarming to Republican voters in Michigan (and Arizona, for that matter) who aren't part of the hardcore base. That is to say, conservative voters who have their doubts about Romney and are receptive to an alternative might now conclude that Santorum is no more credible than Gingrich, Perry or Cain. There are now clear signs that his lead over Romney in Michigan is vanishing. Romney's heavy television presence in the state probably explains most of this, but Santorum's antics threaten to exacerbate the trend.

The bigger problem has to do with the GOP's opinion-shaping elites -- elected officials, party leaders, activists, commentators, media personalities whose views tend to trickle down to the rank-and-file. An unusually high number of elites have remained on the sidelines so far. Since grabbing the spotlight two weeks ago, Santorum has essentially been auditioning for them. If he can show them he's for real, their support would radically enhance his prospects of winning the nomination, amplifying his own message, giving him invaluable cover against Romney attacks, and funneling serious money into his campaign (and a super PAC). But so far, he's won very few new converts; Mike DeWine, the former Ohio senator and current attorney general, is the highest-profile endorsement Santorum has snagged.

So for now, at least, Santorum is virtually alone as he confronts Romney's money and attacks -- and now a days-long media firestorm over his own comments. It's not a myth that there was, and is, an opening to Romney's right. But Santorum may learn that even in the GOP of 2012, there's such a thing as too much red meat.

Shares