When Jeanette Winterson was a child — a redheaded scrap of a thing, as fierce and self-willed as Jane Eyre but readier with her fists — she went to a school concert at Christmastime with her parents. “Is that your mum?” someone asked her. “Mostly,” was her reply.

Winterson was adopted, raised by evangelical Pentecostals in a working-class town in northern England in the 1960s and ’70s. Her family’s house had no phone, no indoor toilet, intermittent heat and electricity and not quite enough food. Of the six books allowed on the premises, three were either the Bible or Bible commentaries. To the dismay of her mother, Winterson turned out to be brilliant, literary, defiant and gay.

As a young writer, winning the Whitbread Prize for First Novel in 1985, making Granta’s 1993 list of the best young British novelists (along with Kazuo Ishiguro and Alan Hollinghurst), Winterson burned bright, using her childhood and her rebellious sexuality as fuel. “Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit” was her autobiographical coming-of-age novel, funny and harrowing. The two books that followed, “The Passion” and “Sexing the Cherry,” retained much of the escape velocity that got Winterson out of Accrington, Lancashire, and into Oxford and the London literary world. The ones after that were less successful, thematically diffuse grab bags of big ideas with story lines that tend to wander off into the tall grass and stall. Many fans lost interest. As badly as Winterson needed to break free of her youth, its constraints gave form and focus to her intensity.

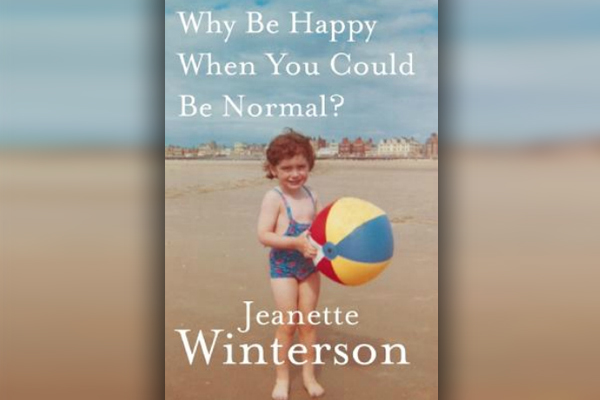

Now Winterson has returned to her origins, with a memoir, “Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?,” that recounts the real-life basis for “Oranges,” a novel that Winterson describes as “the cover version … a story I could live with” when “the other one was too painful.” The occasion was Winterson’s decision, in 2008, to search for her birth mother. Not surprisingly, this quest led to a reassessment of the woman who raised her and whose “dark orbit” shaped her life. “I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t setting my story against hers,” Winterson writes. “It was my survival from the very beginning.”

Mrs. Winterson (as the author likes to call her), is also — like it or not — the novelist’s muse. The subject matter of “Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?” (titled after a question Mrs. Winterson asked her teenage daughter when she refused to give up her female lover) restores Winterson to her full power. This isn’t a retread of “Oranges,” but a reconsideration of that novel’s terrain. There’s always been something Byronic about Winterson — a stormily passionate soul bitterly indicting the society that excludes her while feeding on the Romantic drama of that exclusion — but Byron died at 36. Winterson, at 52, offers a glimpse of how such figures age and, if they’re lucky, even mellow. Just a bit.

Winterson’s mother and father converted to Pentecostalism at a tent revival, and one of the more refreshing aspects of “Oranges,” also reflected in “Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?,” is Winterson’s often fond remembrances of her church. It was repressive and puritanical with respect to many ordinary pleasures (her mother referred to Woolworths as a “Den of Vice”) but there was also “the camaraderie, the simple happiness, the kindness, the sharing, the pleasure of something to do every night in a town where there was nothing to do.” Faith gave Winterson and her co-religionists purpose. “I saw a lot of working-class men and women — myself included — living a deeper, more thoughtful life than would have been possible without the Church.”

Her mother, however, latched on to Christianity’s doomsday aspect. When most children learned to make little presents for Santa, Winterson crafted for the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Her mother’s favorite hymn was “God Has Blotted Them Out,” “which was meant to be about sins, but really was about anyone who had ever annoyed her, which was everyone.” In her mother’s fantasy of heaven, she got to live alone, in a big house, with no neighbors. In that spirit, Mrs. Winterson never gave her own daughter a key to the family house and often made Jeanette sleep outside, on the doorstep, when she’d been naughty.

Yet Mrs. Winterson was also a compelling presence, “out of scale, larger than life. She was like a fairy story where size is approximate and unstable.” She taught her daughter to read using the Book of Deuteronomy — “because it is full of animals (mostly unclean)” — and drew illustrations of all the creatures. She read aloud (from the Bible, of course) to the delight of her husband and child, who found it “intimate and impressive at the same time.” In a passage that neatly encompasses the Wintersonian take on the North’s droll vernacular shot through with flashes of high rhetoric, she writes of the time “our gas oven blew up. The repairman came out and said he didn’t like the look of it, which was unsurprising as the oven and the wall were black. Mrs. Winterson replied, ‘It’s a fault to heaven, a fault against the dead, and a fault to nature.'”

Winterson also has a knack for aphorism; this is a book that will inspire much underlining. Babies are “raw tyrants whose only kingdom is their own body.” Literature is not superfluous to the working class because “a tough life needs a tough language — that is what poetry is. That is what literature offers — a language powerful enough to say how it is.” Young Jeanette’s great salvation was the section in her local library marked “English Literature: A to Z,” which she proceeded to read straight through in alphabetical order. “Fiction and poetry are doses, medicines,” she explains. “What they heal is the rupture reality makes on the imagination.”

Because fiction was forbidden in her house, Winterson squirreled away paperbacks, obtained from the rag-and-bone man, under her mattress. (“Seventy-two per layer can be accommodated.”) In time, the rising level of her bed aroused her mother’s suspicions and the books were discovered, extracted and then burnt in the backyard. This, and the punitive beatings that her weak father administered at her mother’s insistence, caused Jeanette to hate her parents, “not all the time — but with the hatred of the helpless; a flaring, subsiding hatred that gradually became the bed of the relationship. A hatred made of coal, and burning low like coal, and fanned up every time there was another crime, another punishment.”

Nothing, however, matched the fury that greeted the discovery of Winterson’s affair with another girl in the church at age 16. She was subjected to a brutal “exorcism” — three days without food or heat, sleep deprivation, more beatings and a church elder who foolishly tried to molest her with the promise that “it would be better than with a girl” (she nearly bit his tongue off). Not long after that, her mother kicked her out and for a while she lived in a friend’s car before being taken in by a teacher and working her way from community college to Oxford (where her tutor informed her that she was “the working-class experiment”).

The narrative takes a big leap after that. Twenty-five years later, and Winterson suffers a breakdown (which she refers to as “going mad”) and contemplates suicide. A new romance (with the celebrated psychoanalyst and author Susie Orbach — possibly responsible for such occasional and regrettable lapses into psychobabble as “It takes courage to feel the feeling”) and the urging of friends persuade her to search for her birth parents. Much wrangling with obtuse bureaucrats ensues. The results are not entirely what she expected: a renewed appreciation for the adoptive mother who treated her so badly.

Winterson seems to marvel at her expanding capacity for forgiveness and compassion, though in truth the strength of her writing about this period in her life has always been its generosity. “She believed in miracles, even though she never got one — well maybe she did get one, but that was me, and she didn’t know that miracles often come in disguise,” she writes of her mother. True enough. Mrs. Winterson was also Jeanette’s miracle in disguise. To summon the energy to catapult herself out of that dingy row house in Accrington, the fledgling writer needed to transform herself from Devil’s spawn to Promethean hero. The measure of any hero is the size of his archenemy; that’s why Sherlock Holmes needs Professor Moriarity to truly come into his own. “She was a monster,” Winterson writes, “but she was my monster.”