American journalists love to write about the violence that afflicts Ciudad Juárez, the sprawling city of 1.3 million just across the river from El Paso, Texas. It’s a quick jaunt across the Rio Grande, after all, and a guaranteed story. Thanks to a ghastly combination of warring drug cartels, poverty and virtually ineffectual law enforcement, the city has become one of the most dangerous in the world. Last February, for example, 229 Juárenses were murdered, more than 10 per day.

But not many gringo journalists spend more than a few days in Juarez. None — at least that I know of — move there. Nor do they make much effort to write about what it feels like to live in the city, as opposed to dying there.

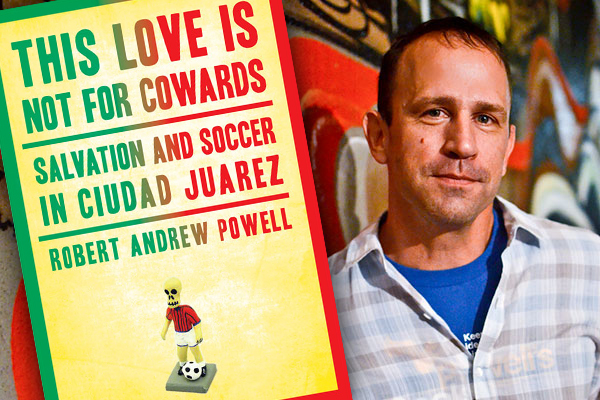

Which is what makes Robert Andrew Powell’s new book, “This Love Is Not for Cowards,” so gripping. It tells the bittersweet story of Juárez’s hapless professional soccer team, Los Indios, and the rabid fans who support them. The book reads like a mashup of Nick Hornby’s “Fever Pitch,” Bill Buford’s “Among the Thugs” and Charles Bowden’s grim 2010 survey of Juárez, “Murder City.”

Salon spoke to Powell — a journalist who has written for the New York Times Magazine, Sports Illustrated, Mother Jones, among many other publications — from his home in Miami.

Why did you move to Juárez?

I had just squandered three years on a book project in Colorado that never made it into print. I had no job to speak of, and few prospects for freelance work. I had no girlfriend or wife or kids. I had no home, either; I was crashing on a friend’s couch in Miami. Oh, and I was broke, too.

In the context of my life at the time, moving to Juárez was fairly pragmatic. I was fascinated by the city. So many people were being murdered, day after day after day. I couldn’t get my head around it, and I wanted to check it out — no place seemed more relevant. It was dirt cheap. My U.S. cellphone could still pick up a signal in Juárez. And my home country would be literally within walking distance should I ever need anything.

Did you intend to write about the Indios?

No. I didn’t have a book deal, or any magazine assignments. All I knew for sure is that there was a soccer team in the city, that they played in the Mexican major league, and that they had an American on the team, midfielder Marco Vidal. Soccer was something I could understand. I couldn’t comprehend the violence before I moved there, but I could understand sports. I figured if I hung around the team the city would eventually reveal itself.

I’m a big proponent of what Gay Talese calls “the fine art of hanging out.” I knew Marco was an American, but until I got there, I didn’t know his Mexican father had entered Texas illegally, first trying to cross the Rio Grande in Juárez. I knew the owner of the team, Francisco Ibarra, was living in El Paso for his safety, but I didn’t know how painful it is for him to live in another country. I didn’t know an Indios coach would be murdered. I didn’t know that Marco would marry a young Juárez woman, or that her family would flee to El Paso in fear. I didn’t know that the Indios team would lose and lose and lose. If I hadn’t spent a ton of time simply hanging out, I wouldn’t have recognized that the losing could be a metaphor for the city. A lot bubbled up organically.

What did the players and coaches there make of you?

The head coach, every single time he would see me, would shake his head and laugh, like, What the fuck are you doing here, gringo? Why in the world was I volunteering to live in such a violent city? Why was I hanging around a losing team? But I just kept showing up. I went to every practice, every day. I flew with the team on road trips, staying in the same hotels, attending their meetings and sharing meals with them. I’d squeeze into the locker rooms on game days, quietly taking notes. Everyone eventually forgot I was there, or at least that I was working on a project that would someday become a book. It’s not my nature to take over a room. I like to hang back and observe. I like to watch.

There are moments in the book where you’re witness to intense violence. I’m thinking about the episode in which a guy you’re drinking with goes outside and viciously assaults another man, then runs back into the bar. Did you feel at all complicit?

Complicit? Nah. I wasn’t killing anyone. I didn’t beat anyone up. I rarely even raised my voice. But overwhelmed? Yep. Powerless? Sure. The violence was incredible, and it affected everything, even if I would go long stretches without seeing any dead bodies.

That was the surreal thing: how normal everything could seem, or at least how normal everyone tried to act. I’d go to practice, I’d get some lunch, I’d watch TV or go to a movie with my friends. Then the next morning I’d read in the newspaper that a dead body had been dumped on my block the night before, a man with his penis sliced off and shoved in his mouth. If I hadn’t read the story, I wouldn’t have even known it happened. When I did see or hear about something, I learned to shrug it off. In the book I compare life in Juárez to “The Lottery,” that Shirley Jackson short story. We knew that a few of us would be chosen for the daily killing ritual, that the odds of being chosen were very small, and that the killing was simply a cost of residence.

When did you decide to head back to the States?

There was a car bombing. Four first-responders were killed. And I happened to be right down the street when the bomb went off. It wasn’t the explosion that freaked me out so much, or that I had been so close to it. It’s that it didn’t freak me out at first, that I’d grown so accustomed to violence. I even jogged the next afternoon down the very street where the bomb exploded. But a few days after the bombing, a friend in Juárez ended up metaphorically slapping me across the face to show that I’d grown numb. And when you grow numb in Juárez, that’s when you have a problem. He convinced me that I had to leave.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the book was your reexamination of Juárez’s portrayal in the media, in particular the trumped-up claims about young women being targeted by serial killers. Can you talk about why you decided to write about this? Why you didn’t just stick to soccer?

I never intended to write a book about soccer, but about Ciudad Juárez. I couldn’t seriously look at the city without looking at the dead women, which, in popular consciousness, is what Juárez is known for, above all. There’s a well-established narrative of young girls who work in the maquiladoras being snatched off the streets and murdered, supposedly just because they are women.

When I moved to the city, I believed the narrative. I had no reason to doubt it. Amnesty International is behind it, and they’ve won a Nobel Prize. All the big news outlets have publicized it. Roberto Bolaño placed the killings of the women at the center of his book “2666.” I’d watched a few films, too, both Hollywood and documentary, that showed how women are especially vulnerable in the city, and how Mexican men can’t handle the growing independence of the factory-working women in their lives. How NAFTA is to blame, too, and also, come to mention it, how serial killers and spree killers and organ harvesters and random sociopaths are equally to blame. The government cares so little about women, according to the popular narrative, that it refuses to resolve any of the “femicides,” or female murders.

But living there, I began to see that the popular narrative didn’t jibe with the world around me. Relatively few of the female murder victims are girls. Almost none of the female victims ever worked in a maquiladora. Women are being killed in the city, often in horrible ways. But many, many, many more men are being killed at the same time. Also in horrible ways. And the government doesn’t investigate these male murders, either. They don’t investigate anything! Murder really is effectively legal in Juárez. This failure of basic government, which in Juárez is sarcastically called “a weak judicial system,” has nothing to do with gender.

Proponents of the femicide [narrative], most with the best of intentions, have been extremely effective in taking the generalized violence in Juárez and turning it into something that supports their agenda. I came to call it the “femicide business.” As in any business, there are people profiting. The traditional narrative has funded their clinics and/or won them academic positions and/or book deals and/or paid speaking opportunities at conferences. Most reporting on femicide ranges from disgustingly opportunistic to depressingly sloppy. Again, so many people who write about Juárez never visit the city, or if they do they parachute in for only a day or maybe two, with their stories already plotted in advance. “Google journalism,” I call it. My time in Juárez has radicalized me against it. There needs to be more hanging out.