For those interested in American politics, the national media provide all the information they could want, in the form of live reports from the campaign headquarters and campaign buses of candidates, constant updates of polling numbers, interviews with voters alone and in groups, clips of speeches, animated maps of states and counties and congressional districts — everything except the one thing that would make sense of it all: regional political geography.

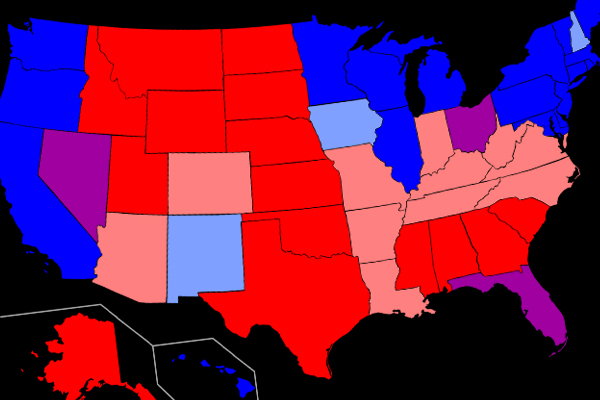

The importance of geography in American politics could not be clearer. To begin with, there is the red state-blue state map, showing Republican-leaning states in the form of an L uniting the West and South and Democratic-leaning states clustered in the Northeast, around the Great Lakes and on the West Coast. From election to election, states shift from one color category to another, but the pattern remains remarkably stable.

Within parties, geography is just as important. In the Republican primaries, Mitt Romney’s base is the Northeast and parts of the West. Rick Santorum does best in the Midwest, Newt in the South.

Geography was just as important in the Democratic primaries during the contested presidential nomination race of 2008. After John Edwards dropped out of the race, Hillary Clinton did well in Greater Appalachia while Barack Obama racked up votes in the Plains states.

Nor is the centrality of region in American politics new. Regional differences not only date back to the beginning of the nation but almost destroyed it during the Civil War. Unfortunately for politics as an exciting spectator sport, large parts of the country tend to vote for one of the two major parties for decades or generations, a fact that limits the horse races to a few swing states in any given era. (See “Florida, 2000 Recount in.”)

Given the importance of geography in our politics, you’d expect political reporters and other commentators to be explaining why different regions vote in different ways. Unfortunately, you can watch many successive 24-hour cycles of political news coverage without getting any adequate analysis of political regionalism.

It’s not that America’s political commentators lack interest in demographic factors that influence politics. On the contrary, they are obsessed with a small number of demographic characteristics, chiefly race and sex. Viewers or readers are told endlessly about the gender gap and racial/ethnic differences in voting. But you would fall asleep waiting in vain for a political reporter on TV to explain differences between the Highland South and the coastal South or to describe the distinctive political culture of the states in the Midwest settled by New Englanders.

In the world of our political media, there are generic whites, generic Latinos and generic African-Americans from coast to coast. The categories are sometimes refined by class, but this still produces hopelessly vague descriptions — treating Italian-Americans in Rhode Island as though they are part of the same generic “white working class” to which many Scots-Irish Tennesseans and Norwegian-American North Dakotans also belong. These fuzzy definitions all too often harden into cartoonish stereotypes like the “Angry White Male” of a few decades ago or “NASCAR Man” more recently.

A news junkie who follows the American political media could be forgiven for thinking that the American people are divided by race and gender, and perhaps religion, but not by regional culture. And yet the evidence says otherwise. Latinos in Texas vote differently than Latinos in California. Scholars have established that members of the same religions — Protestants, Catholics and Jews — tend to be more socially conservative in the South than in other parts of the country. Regional political culture is a powerful independent force, not a mere reflection of the numbers of particular demographic groups in particular territories.

As many scholars have observed, immigrant groups tend to assimilate, not to a generic American culture, but to particular regional cultures. Michael Dukakis and Ralph Nader are, respectively, cultural Yankees of Greek and Arab descent. Bobby Jindal is a Southerner of Indian ancestry. Where you grow up is often as important, if not more important, than where your family came from.

But cultural regions are absent from most media discussions of politics, other than the most cursory references to Southern conservatism and West Coast liberalism. At their worst, when they cannot ignore regional political culture, media pundits try to explain it in terms of the categories they prefer, like race and gender. For example, during the 2008 race, some commentators explained regional support for Hillary Clinton simply in terms of white racism. It was clear, however, that differences in regional culture had more explanatory power. Obama’s aloof and professorial manner fitted poorly with the populist political culture of Scots-Irish Appalachia, but resonated with, or at least did not repel, the low-key, introverted culture of the heavily Germanic-American northern Plains states.

The exceptions among prominent political analysts like Michael Barone prove the rule. What makes the neglect of region by highly visible political reporters and commentators all the more puzzling is the fact that regionalism in American politics has generated a vast and growing scholarly literature. There are older classics like Daniel J. Elazar’s “American Federalism: A View From the States” (1966) and David Hackett Fischer’s “Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America” (1989).

Joining these are recent books that take political regionalism seriously: Earl and Merle Black’s “Divided America: The Ferocious Power Struggle in American Politics” (2007), Nicole Mellow’s “The State of Disunion: Regional Sources of Modern American Partisanshp” (2008) and Colin Woodard’s “American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America” (2011).

These and other scholars disagree on the number and definition of American regions. To name only the most recent studies, the Blacks identify five, Mellow four and Woodard 11. But it is clear that these are slightly different maps of the same reality.

Why not invite scholars like these who actually understand America’s regional cultures onto TV news studio sets? As part of election night coverage, wouldn’t it be useful for journalists to interview political historians and political scientists to put election returns into their historical regional contest? Wouldn’t that be an improvement over turning for commentary to partisan flacks sitting on stools in the studio and reciting pre-packaged talking points?

To be sure, the kind of regional cultural analysis that is necessary to understand American politics requires reporters and commentators themselves to do some homework beyond simply checking Gallup polls and how they break down by race, gender and ethnicity. It might require TV talking heads to read a book or two (or at least delegate the task to a 20-something research assistant).

Clearly traveling with candidates across the country in buses is not enough to educate our journalistic elite about the central fact of American politics: regionalism. By all means, let them spend time on the bus. But they need to spend a few hours in the library.