After a Navy SEAL team killed Osama bin Laden at his Pakistan hideout a year ago this week, it flew his body to the Arabian Sea, weighted it down, and slid it silently off an aircraft carrier into the watery depths.

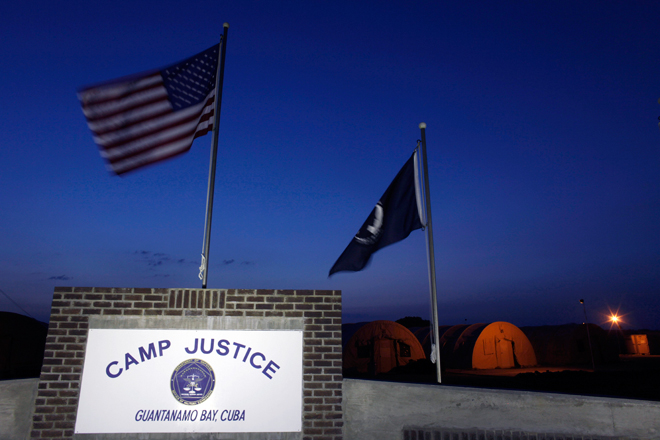

For many Americans, the secret raid provided a measure of revenge and catharsis for the strikes of Sept. 11, 2001. But it didn’t provide the kind of justice and official reckoning that the country needs to gain real closure. Now the government has a chance to achieve that through a full, fair and open trial of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four co-defendants, so the world can finally see the evidence against him as the true architect of the attacks on New York and Washington. The trial kickoff — an arraignment for the men — is scheduled for this Saturday at the U.S.-run detention facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

This should be our Nuremburg, the defining trial of the 9/11 era and a fitting coda to it.

Unfortunately, the U.S. government appears to be on the verge of squandering this opportunity, and with it, the best, and perhaps only, chance for the public to understand not only how the attacks came to be, but why Mohammed waged a relentless war against America and how we might stop the next would-be terrorist mastermind.

The problems lie within the reformed military-tribunal system that the Obama administration put in place after losing its fight for a civilian trial in New York. Political compromises have resulted in a flawed military commissions process that from outward appearances is not only rigged against the defense, but hyper-choreographed, censored and hermetically sealed.

“The process is designed to achieve a conviction, and to do it with as little revelation as humanly possible, but with the veneer of due process and justice,’’ said one participant who said restrictive gag orders prohibited him from talking publicly. “You’re talking about the most heinous crime ever, and we’re going to afford them less due process, less discovery, less of everything than we would the guy who shoplifted a pack of gum from CVS.’’

Obama administration officials say their reformed military commissions system is a vast improvement over the Bush administration’s version, which Obama moved to shut down on his first day in office in 2009.

Defense lawyers disagree, and insist they have been hamstrung in their efforts to mount the kind of aggressive defense needed to do their jobs including full and unfettered access to evidence, witnesses and even the accused themselves.

Four of the five legal teams had so few of their key players in place in recent months that they did not file the “mitigation submissions’’ that the government said it needed to decide which of the five men should face the death penalty and other key issues, such as whether to try them together or individually. They recently filed motions asking that the charges be thrown out because of fatal flaws in the system, which they say make it impossible for them to defend their clients.

“It’s window dressing,’’ Mohammed’s defense lawyer, David Nevin, said of the government’s improvements. “I am not all satisfied that it is a fair process. In fact, it is not a fair process.’’

Many of the defense lawyers have quit out of frustration or for other personal reasons stemming from the many delays in the process. Only a few have been there long enough to even begin to understand their clients’ case, not to mention the convoluted military commission process.

And they say they will be unable to effectively challenge confessions obtained when their clients were coercively interrogated in the CIA’s black site prisons, if they can broach the subject at all. This is important for the four men accused of helping Mohammed with the logistics of the plot. Several claim they have been wrongly accused, tortured into confessing, or both.

It is also important with regard to Mohammed, who confessed to dozens of plots while being waterboarded 183 times, and has said he may plead guilty even before the trial begins. Few U.S. counterterrorism officials believe all of his often boastful confessions, and it is important for the public to hear what, exactly, evidence the government has with regard to what he did and didn’t do, and whom he might have been protecting.

The team of Defense and Justice Department officials overseeing the military commission process, and the presiding judge, should quickly address the defense lawyers’ complaints, or a proceeding that some call “The Trial of the Century’’ will be delayed further by legal wrangling — and forever tainted by accusations of being unfair.

A full, fair and transparent trial, above all, will benefit the public. There is much the public doesn’t know about Mohammed, including the details of how he devised the plot, convinced bin Laden to let him do it and then orchestrated it “from A to Z,’’ to use his own words. It was Mohammed who masterminded dozens of other plots and attacks, some while staying a step ahead of the largest-ever criminal manhunt.

Mohammed, not bin Laden, was the one who traveled the world as a kind of “Johnny Appleseed’’ of terrorism, establishing alliances and creating a network of cells and lieutenants that in some cases remains today. And it was Mohammed who personally recruited young jihadist prospects much like a baseball scout, many of them Westerners, tapping into their grievances to turn them to his cause.

The U.S. government has kept the details of what Mohammed did — and how and why he did it — hidden in its most classified files since his capture in Pakistan nine years ago. The government should set the record straight on that, because there is an important lesson to be learned from the largely untold tale of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed: It isn’t some monolithic group like al-Qaida that poses a continuing threat, it’s the one intelligent and energetic person who can emerge from nowhere and orchestrate a 9/11 while the world focuses elsewhere.

To that end, the government should declassify as much evidence as possible, and explain how it obtained it. It should call numerous witnesses to testify, especially since the one who has been publicly identified, Majid Khan, claims he was tortured while in CIA custody overseas.

Instead of limiting access to a few closed-circuit TVs, it should consider televising the proceedings. It should ensure that censorship is minimized, and used only to protect intelligence sources and methods, not to save the government from embarrassment. And it should let Mohammed and the others testify at length on their behalf if they so desire.

By doing so, the Obama administration will be able to say it did its best to put on the kind of civilian trial it has wanted all along, and one with a similar outcome to that of the al Qaida members charged with blowing up two U.S. embassies in Africa in 1998.

Those of us who witnessed that trial in Manhattan in 2001 saw the defendants squirm in their chairs as prosecutors introduced mountains of evidence against them. We saw eyewitnesses point the finger at the accused, and surviving victims glare at them from the pews.

We heard from the terrorists themselves, and learned a lot about why they did it, about how terrorist networks operate and about what might be done to stop people like them. And when the jury convicted them, there was no question that justice was done.