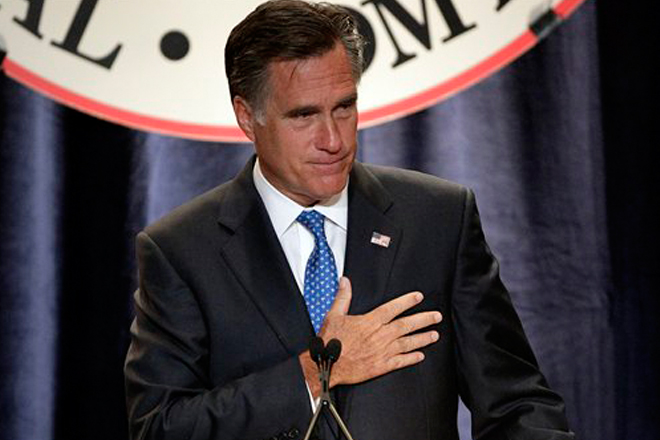

Don’t believe the hype about the supposedly narrow path to 270 electoral votes that Mitt Romney faces. The idea, advanced in a Washington Post story today, is that the presumptive GOP nominee faces an extra burden this fall in the specific swing states that will ultimately decide the presidency.

The claim has been made by others recently, and there’s really nothing to it. At its core, it reflects a very simple fact: Barack Obama won the 2008 election. Just consider the opening line of today’s Post story:

Mitt Romney faces a narrow path to the presidency, one that requires winning back states that President Obama took from Republicans in 2008 and that has few apparent opportunities for Romney to steal away traditionally Democratic states.

The first part of that sentence, as Nick Baumann pointed out, is “literally true of every nominee for the party that lost the previous election.”

This speaks to the political world’s very human tendency to treat the patterns that defined the most recent election as more fixed than they are – which inevitably leads to wild overreactions when those patters are obliterated by the next election. Remember the “permanent Republican majority” that Bush and Rove put together in 2004? And how just two years later Democrats won back the House and the Senate? Or how Barack Obama put together a 40-year majority in 2008, only to watch Republicans score one of history’s most thorough midterm landslides in 2010?

The same impulse is behind the “narrow path” conventional wisdom about Romney. There’s an assumption that Romney is automatically facing an uphill battle in just about every state that Obama carried in 2008. And since Obama’s overall poll numbers are still decent (he leads Romney by 3.3 points in Real Clear Politics’ national average), he is (not surprisingly) still ahead in most of the states that he carried in ’08, which makes it seem like Romney faces an extra-heavy lift in getting to 270.

But it’s almost all an illusion. As Mark Blumenthal noted today, if Romney overtakes Obama in the national horserace, the swing states will follow. Granted, it will take a bigger national swing to flip some states than others (a one-point Romney edge nationally probably won’t bring Pennsylvania into his column, for instance), but the Electoral College will almost certainly take care of itself if Romney is the national winner. In most battleground states, there just isn’t an extra built-in advantage for Obama that would shield him from national movement toward Romney.

If anything, the “narrow path” talk calls to mind the Republican Party’s famous “lock” on the Electoral College, which became convention wisdom after the 1988 election – when the GOP won the White House for the fifth time in six elections. As it was explained at the time:

[T]he GOP formula: appeal to patriotism and traditional values to sweep the South, piling up about half of the 270 electoral votes needed for election; add California, the biggest prize, and a dozen other states in the inland West; score well enough among blue-collar ethnics in the industrial Midwest, and you’ve got a lopsided victory. The recipe worked five of the past six times.

Actually, what had worked for the GOP in five of the previous six elections was a favorable national climate (Vietnam/LBJ fatigue in 1968, a weak economy when Jimmy Carter ran for reelection in 1980, a strong one when Ronald Reagan ran for reelection in 1984, etc.), which produced several epic national landslides. The GOP’s success in these races wasn’t the result of an Electoral College numbers trick; it was a result of being the preferred party of the majority of Americans. And sure enough, just when the GOP “lock” became an accepted rule, Bill Clinton came along and capitalized on a favorable climate for his party (the early ‘90s recession), gobbling up 370 electoral votes and routing George H.W. Bush in 1992.

As the 2000 election showed, it’s not automatic that the Electoral College will validate the national popular vote. But for there to be a variance between them, it takes a truly unique set of circumstances, which can be impossible to plan for. After all, until Election Day 2000, Democrats and Republicans agreed that if there was a split verdict, it would be the result of George W. Bush winning the most popular votes and Al Gore carrying the Electoral College. The bottom line: If Romney pulls ahead in the national horserace, the talk of Obama’s big Electoral College advantage will go away.