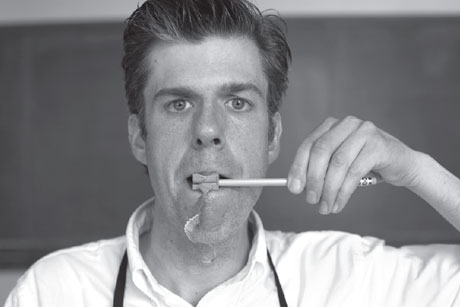

“How to Sharpen Pencils: A Practical and Theoretical Treatise on the Artisanal Craft of Pencil Sharpening” (Melville House, $19.95), by David Rees, is not your average book about pencil sharpening. In this digital-desktop age, it’s a keenly rigorous plea for the sanctity of a soon-to-be-forgotten skill. Rees, a veteran political cartoonist and “the number one #2 pencil sharpener,” has penned (or, rather, penciled) a survey of the art and science of getting to the point. I caught up with him over e-mail while he was in the middle of a marathon sharpening session. You are the only person I know who could make an entire book about pencil sharpening.

“How to Sharpen Pencils: A Practical and Theoretical Treatise on the Artisanal Craft of Pencil Sharpening” (Melville House, $19.95), by David Rees, is not your average book about pencil sharpening. In this digital-desktop age, it’s a keenly rigorous plea for the sanctity of a soon-to-be-forgotten skill. Rees, a veteran political cartoonist and “the number one #2 pencil sharpener,” has penned (or, rather, penciled) a survey of the art and science of getting to the point. I caught up with him over e-mail while he was in the middle of a marathon sharpening session. You are the only person I know who could make an entire book about pencil sharpening.

When Melville House approached me about doing a book, it took me a few weeks to figure out how to structure it. Once I decided to build the text around different sharpening techniques, I panicked that I wouldn’t be able to write enough. In the end, though, we had to cut almost 50 pages from the final manuscript. I love writing about pencil sharpening!

One of the more difficult aspects of sharpening is the little plastic pencil-case sharpeners. It is easy to break the point. And speaking of points, what is the genesis of this idea?

You are referring, of course, to the tyranny of the irregular pin tip, a common complication associated with suboptimal deployment of a single-blade pocket sharpener. This is covered in chapter five of my book, as are other problems like the irregular collar bottom, the “headless horseman,” and the off-axis graphite core. As to the genesis of this project: I rediscovered my love of sharpening pencils while working for the U.S. Census Bureau in the spring of 2010. Our first day of training involved sharpening pencils with a U.S. government–issued pocket sharpener. I decided then and there that I was going to figure out how to get paid to sharpen pencils. I’m happy to report that I have now made more money sharpening pencils than I made working for the census.

You’re truly on to something. The other day I was trying to figure out what to do with my Dixon Ticonderoga no. 2. What is it you want to say to your audience?

In this era of iPads and digital styluses, I want to remind my readers that the humble pencil remains an astonishingly efficient and elegant mark-making device, and it behooves us to sharpen pencils as well as we can. I leave it to others to decide whether the entire book is an extended metaphor for living your life as well as you can in the face of frustration and heartbreak. I can scarcely believe I’m capable of such a grandiose meta-textual coup, but I just might be.

I foresee a run on stationery stores once this book is published. Are you prepared to help get the lead out?

This is an unforgivable pun, and it is only thanks to my professional discipline that I will continue to answer your questions rather than throw my computer out the window in a blind rage.

I see you’ve been experimenting with the position of wall-mounted sharpeners. Do you advise any particular height?

Although wall-mounted sharpeners are usually positioned such that the average user may access the device while standing, urban explorers may encounter sharpeners outside the typical “strike zone.” My book describes three options for using a wall-mounted sharpener located within two feet of the floor; it also describes how to properly deploy a stepladder in order to enjoy a sharpener located within two feet of the ceiling. (I don’t mind admitting that I almost fell from a great height during the photo shoot for the latter strategy. Such are the risks associated with “extreme pencil-pointing.”)

This book does for writers, artists, contractors, flange turners, anglesmiths, and civil servants what “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” did for flange turners and anglesmiths. Since your other books were rooted in current politics, do you have any guilt or remorse in doing a book that is simply about pencils?

I spent seven years as a left-wing political cartoonist, keeping abreast of the latest atrocities and tragedies associated with the global war on terrorism. It was at turns exhilarating and enervating. I turned to sharpening pencils as a respite, and it pleased me to write a book with exactly zero partisan subtext. It is my hope that Red America and Blue America can come together as Yellow America, both sides lending their voices to the chorus of praise due the classic yellow no. 2 pencil (and, by extension, ME).

With the election season coming, are you totally fixated on pencils, or does political cartooning still have a place in your case?

I’ve started making cartoons for Rolling Stone again. “Get Your Vote On” will run until Election Day.

I understand (in fact, you told me) that you want to do stand-up comedy. Does this book get you closer to the microphone?

Alas, no. This book pushes me away from stand-up comedy with great force and extreme prejudice. Sharpening pencils requires a steady hand and a clear eye, two qualities sorely lacking in the typical comedian—a specimen whose job preparation usually involves ingesting alcohol and cocaine with coequal ferocity, thereby compromising fine-motor skills. (One shudders to think of the pencil points conjured by a Sam Kinison or an Andrew “Dice” Clay; the term “beaver-savaged breadsticks” comes to mind.) With this book I turn my back on the prospect of amusing an audience and embrace the humorless passions of the artisanal craftsman.

Search as I might, I could not find anything on that other pencil scourge, broken (or chewed-off) erasers. Do you have a solution?

I’m afraid I can’t help you, as I have no interest in erasers.

This story appears in the June 2012 issue of Print.