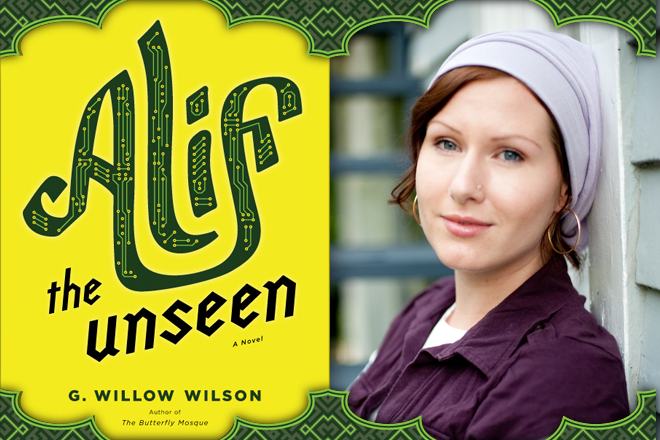

Arthur C. Clarke famously said that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” which may explain why fantasy narratives have enjoyed a resurgence of popularity in this age of wondrous gadgets. In G. Willow Wilson’s equally wondrous “Alif the Unseen,” the connection between the two is more than just metaphor, although as far as this book is concerned, metaphor itself is a kind of technology.

The setting is the capitol of a nameless Persian Gulf emirate — the characters refer to it only as “the City” — and our hero is teenage Alif, although that’s only his nom de Internet. He supplies untraceable Web hosting to an assortment of incompatible clients, from Islamists to communists to feminists, whoever wants to evade detection by the region’s despotic authorities. “I’ll help anyone with a computer and a grudge,” he tells Dina, the girl next door, an annoying pious childhood friend whose face he hasn’t seen in the 10 years since she put on the veil.

The novel opens with Alif desperately trying to contact Intisar, a rich, aristocratic Arab girl he met online; she’s cut short their brief affair with no explanation. Since he’s not-so-rich and half-Indian — the son of an Arab businessman’s second wife — it’s not hard to guess why, in their racially stratified society, Intisar sees the romance as a dead end. Heartbroken, Alif complies with her request to “make it so I never see your name again,” by devising a program that can “recognize a single human personality irrespective of what computer or email address or login he’s using.” If he makes it impossible for her to find and contact him, then he’ll never have to know if she did, or didn’t, try to.

Alif’s invention exceeds his wildest dreams, and even his own comprehension. It also attracts the attention of the Hand of God, the nickname Alif and his “gray hat” hacker friends have given who- or whatever fearsome entity conducts Internet policing for the regime. At the same time, Alif comes into possession of old and strange-smelling book of stories, “Alf Yeom: The Thousand and One Days.” Days, not nights. Hmmm.

As a result of these two not unrelated developments, Alif ends up on the run. His search for an underworld figure calling himself Vikram the Vampire plunges him into the hidden world of the jinn, beings from Arabian mythology who live parallel to, but largely unseen by, our world. Vikram mostly looks like a handsome, “raceless” man, except when you glimpse him from the corner of your eye and realize his knees bend the wrong way. As characters in this sort of story are wont to do, Alif picks up companions in his adventures: Dina, an American known only as “the convert,” a kindly imam and a legendary hacker who turns out to be a member of the royal family.

It’s difficult to convey how outrageously enjoyable “Alif the Unseen” is without dropping names — the energetic plotting of Philip Pullman, the nimble imagery of Neil Gaiman and the intellectual ambition of Neal Stephenson are three comparisons that come to mind. Yet I’d hate to give the impression that the novel lacks freshness or originality. Yes, Wilson riffs affectionately on such pop culture tropes as the bar scene from “Star Wars,” introducing Alif and his friends to a tavern in Irem, the City of Pillars, a legendary lost metropolis in the Arabian desert that Wilson envisions as the capitol of the jinn. The clientele is appropriately weird, but they’ve got a flat-screen playing Al Jazeera nonstop. And they’ve got Wi-Fi.

There are darker citations as well. The Hand, when Alif finally comes face to face with him, talks like Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor: “Give the citizens of our fair seaport a real vote and they will do one of three things: vote for their own tribe, vote for the Islamists, or vote for whoever paid them the most money … Would you like to cast bets about the kind of treatment a person like you would get if the Islamists came to power?” The stint Alif does in the State Security Prison is all too believable even as it segues into diabolical nightmare.

Yet for all the richness of the literature — Western and Eastern — it weaves into its own idiosyncratic pattern, “Alif the Unseen” never feels derivative. First, there is Wilson’s deep immersion in the Gulf’s culture, with its distinctive caste system, bickering subgroups and the peculiar lassitude of a people whose lives and speech are strictly controlled. Then there’s the heady fusion of magic and technology, the tantalizing promise of quantum computing and the knowledge of the jinn, which takes the form of stories that can mean several things at once. Given the role that technology has played in the Arab Spring, what might otherwise seem like pie-in-the-sky techno-utopianism and the contrived catharsis of generic fantasy plots, becomes the exhilarating thrum of genuine liberation. Seldom have the real world and the hidden one been so gloriously in sync.