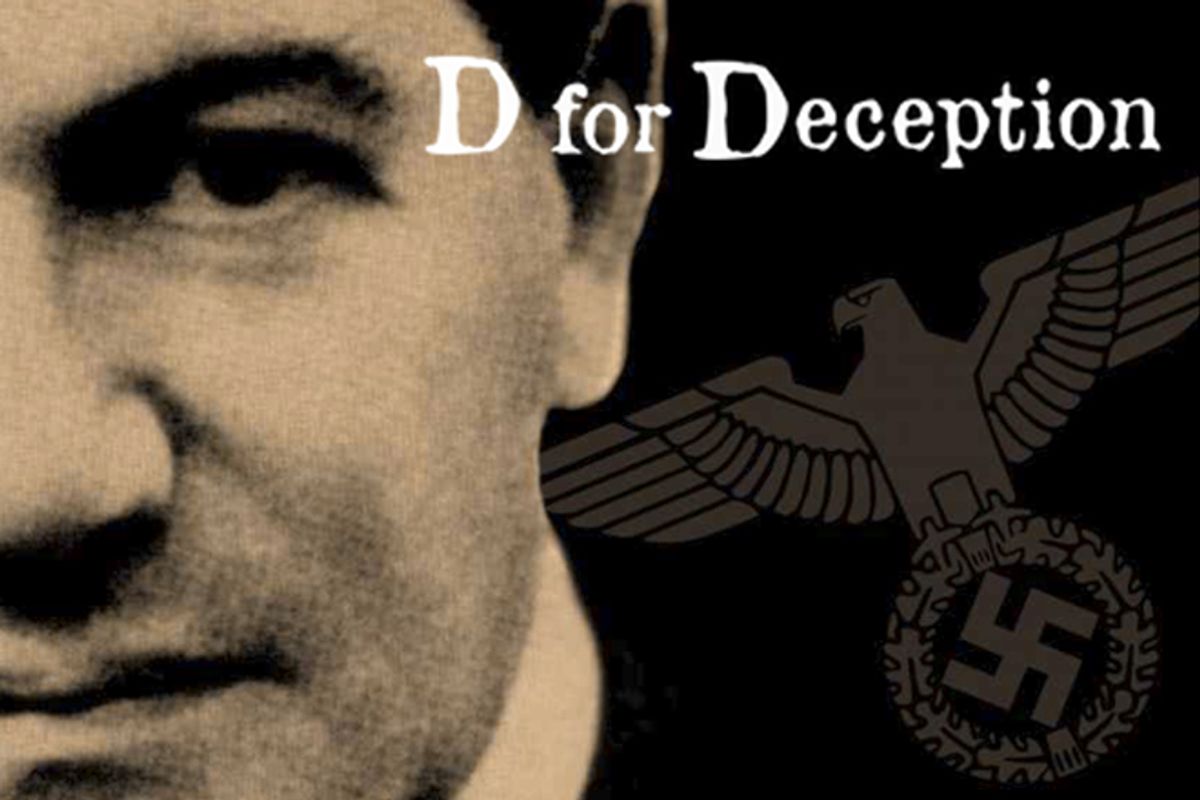

Before there was James Bond, there was Gregory Sallust. Unlike Bond, who is just sexy fun, Sallust was out to trick the Nazis, defeat Hitler and save the world. The debonair anti-Nazi crusader was the most popular fictional hero in England, and Dennis Wheatley, his creator, was the war’s best-selling author, along with Agatha Christie.

Wheatley’s Sallust slips in and out of Germany on spying missions, often at crucial junctures. He tries to overthrow Hitler and bring down Vichy France. It’s all fantasy, of course, except that Wheatley writes around real events in what counted, in the radio era, as real time: His wartime novels appeared only a few months after the events their plots relied on.

And then it got even more real. The British military took notice of Wheatley’s work and thought he might have a thing or two to teach officers and bureaucrats about the Nazi mind. So convincing is Wheatley’s war fiction that Wheatley was taken up as the great imaginary mind of the war, in an effort the Brits dubbed “deception.”

At the request of the Ministry of Defense, Wheatley tried to imagine how the Nazis might invade England, and where. He wrote treatise after treatise, and he suggested counter-attacks: burning Britain’s beaches, mining its coastlines, lighting up its forests. Some of what he suggested was fantastical, but much of it is good – so good that in 1941 Winston Churchill created an entire unit for deception, operating officially as “the London Controlling Unit.”

The unit's job was to bluff the enemy. A simple idea, it's anything but straightforward in practice. "Deception involves choosing a story ... that will be your cover plan. Then you break that story into tiny pieces ... spooning it bit by bit into the maw of the enemy," writes Pulitzer Prize winner Tina Rosenberg. "That is how to write a deception plan. It is also how to write a novel."

That’s what made Wheatley such a natural that he ended up working from Winston Churchill’s bunker with a team of other creatives to write an elaborate cover story for D-Day that was fed straight to Hitler.

Rosenberg uncovered Wheatley’s story on a visit to England, though even the Brits seem to have forgotten him. Rosenberg dug in and discovered a British spy network that managed to spin the very top levels of Nazi command.

In a world before Bond, spy stories literally won the war. Rosenberg’s account of British espionage was published by The Atavist this week.

How did you find the story? Are you a secret reader of vintage pulp fiction?

I’ve always loved spy novels; I think I’ve literally read every single thing [John] le Carre’s ever written. And Alan Furst, I love Alan Furst. But I’ve never been particularly interested in pulp stuff, and then in February, I was on vacation in London, and my husband and I went to the Churchill war rooms. The bunker is now a museum, and there’s this one picture of a guy, and a caption that says he’s the only civilian to have lived here. Another says that this guy was a spy novelist and he wrote the deception plan for D-Day. Which is a huge exaggeration. He and twenty other people did. But I thought, “Oh my god, I know all these spy novelists – Somerset Maugham and Graham Greene and John Buchan – who all did spying first and took what they learned and wrote novels with it.” This is the only example I know of someone who took to novels first and then became a spy.

So I asked people I met in London, “Do you know this guy?” He was the best-selling novelist in Britain, along with Agatha Christie. And no one really knows about this. I interviewed his biographer, who is a brilliant writer, and who wrote a brilliant biography, but who completely skips World War II.

It’s clear you’re fascinated by him, though he’s not very likable. What drew you to him?

He had this really fascinating life; he was a complete dissolute rogue whose best friend was a criminal who got murdered. Wheatley’s own autobiography is so frank about his character flaws, including his womanizing, and yet, he goes from this life of drinking wine into writing bestselling novels almost overnight – and then he turns that into saving the world by fooling Hitler.

The novels were his wife’s idea, right?

He’d always been a story writer. In WWI, he spent a lot of his time in an ammunition job, and he wrote a novel, though it’s unpublished. But his very resourceful wife said, “You’re bankrupt. Let’s make money by writing some fiction.” Because that’s what people did in the evening in the 1930s. They read.

Did you read all of his novels? Are they any good?

There's one he wrote in 1958 where Gregory Sallust induces Hitler to commit suicide in the bunker. I haven’t read that one yet.

I really enjoy them. But they’re terribly written. They’re great on what he calls “snakes and ladders,” getting Sallust into mortal peril every five pages and getting him back out again. It’s very clever, the way he mixes them in with real events and real people, and the analysis is very sophisticated and real. But the guy can’t write. The irony is the stuff he had to do to fool Hitler during the war was far more subtle than anything he wrote beforehand.

How many people were involved with Wheatley in deception?

The chain started with Wheatley, who would invent these bits of disinformation. The last link in the chain was “Garbo,” who was fleshing out the stories and making them plausible. At one point, they would end up on Hitler’s desk a half hour after he sent them, that’s how important he was.

Garbo was also a novelist.

No, he wasn’t. I call him a novelist because he was essentially also writing fiction. He’s the most important spy in the world, and he never spied on anybody. He was a guy from Barcelona who decided he wanted to spy for the British, but the British didn’t pay him any attention. So he said, “I’m going offer my services to Germans so I can come back to the British and have something interesting to sell to them.” The British still aren’t interested, so he sets himself up freelance.

He tells the Germans he went to England, but in fact he went to Lisbon. He buys a travel guide, gets a railway timetable and some maps, and invents these stories, which are completely incredible if you know anything about Britain. But the Germans bought them. He says a convoy sailed from Liverpool to Malta, and the Germans send reconnaissance to try and find it. He has enough authority to get them to move.

Then the British crack the Abwehr code [Abwehr was Nazi military intelligence], and they’re going, “Who is this guy? He got everything wrong about Britain.” The Britain he writes about doesn’t exist. They vetted him and figured out how useful he could be. So they set him up with case officer who spoke Spanish – Garbo did not speak English – and Garbo invented a network of subagents with very complicated lives. They were very Dickensian lives, too, because they had to die suddenly sometimes. If a case was about to lose credibility, the agents would suddenly get very sick. He was writing 2,000-word messages on an almost daily basis. And the Germans trusted him so much they never sent another agent into Britain.

Did Wheatley and Garbo know each other or know about each other?

Wheatley was not supposed to know about Garbo because Wheatley was not supposed to have access to intelligence. But he did know about him; it was too juicy a story not to be shared in the internal environment. Though I don’t think Garbo knew where these plans came from. There are a couple of lines about Wheatley’s wartime life in his autobiography, and he wrote of Garbo with great admiration.

Wheatley has these crazy ideas you catalogue: to barbwire the coast. To cast a mined fishing net two miles offshore. To douse forests in flammable material or light up the beaches in order to “deprive the enemy of the cover of darkness.” Was Wheatley nuts?

He wasn’t nuts. The reason it was useful and credible is it was grounded in astute military analysis. In a sense, he really knew what he was doing. He prefaces his 40 ideas with, here’s our plan: from 50 to 20 to 5 miles off the coast, the plan is this, then this, then this. And then from the coast to inland, the plan is this … He thought about the purpose of each strip of land.

Being a novelist was crucial to being able to come up with ideas that were actually useful within a military setting. If you read the Sallust books, at one point they need to scare the Soviets, who have invaded Finland in the novel, out of a house. How to scare them away? Make believe the house is haunted. Set it up to pretend there are poltergeists and that sort of thing.

Did Wheatley save D-Day?

It’s too much to say he saved D-Day. By the time D-Day came around, there were a lot of people working on this. However in 1942, just before Operation Torch, the invasion of north Africa, he was literally alone.

Was there argument about the D-Day plan?

The plan that they eventually came up with took months to get to. Initially there was real despair about whether they were going to be able to hide [the invasion], to the point where Wheatley worried that they might actually cancel the … deception plan, because nothing looked like it was going to be successful. Hitler knew the Channel invasion was coming. You couldn’t hide it, and you couldn’t hide troops coming over from America and Canada.

The ingenious idea was saying, instead of hiding this military buildup, let’s exploit it. They couldn’t hide the invasion, but they could use that invasion as a feint to hide something else, [a much larger invasion] that was fictional. And they were able to convince the Germans, using recorded military traffic and the double agents’ reports, that this dummy aircraft in Normandy was small – that there was a much larger invasion coming at Pas de Calais. So Hitler didn’t bring troops over to Normandy.

They had some luck, too, the Allies. The regional commander is away celebrating his wife’s birthday, and Hitler’s staff don’t wake him up to tell him about the troops at Normandy until ten hours after they’ve begun landing.

They had a couple pieces of luck. One was the weather, in general, had been very bad; one of the reasons the commander of the Channel forces felt safe to take a few days’ leave was because the weather was predicted to be bad. But they got a one-day break on the weather. Another thing that was huge was that the Abwehr was terrible at its job. They were completely gullible, fooled by Garbo and other people, corrupt, but they were probably also trying to sabotage Hitler. They did not like Hitler.

Should the Pentagon be hiring American novelists?

Deception is different today. Now we can see everywhere, so you can’t do the same kind of work the Brits did. The British could do what they did because the Germans could not see into Britain. They couldn’t penetrate the skies because of the Royal Air Force, and they had no agents, although they thought they had agents. That made the work Wheatley was doing possible. Now, with satellites, you can see everywhere.

Shares