By 1970, Richard Nixon badly wanted to be rid of his Housing and Urban Development secretary, a liberal Republican and former governor of Michigan named George Romney. Romney had a strange dedication to racial integration and had been generally making a hash of the president’s “Southern Strategy” by withholding housing funds from projects that barred black families. But Nixon found it difficult to fire people himself (he preferred to have H.R. Haldeman or John Ehrlichman do it, until he had to fire them), and so he instead got Romney to agree to cease promoting integration in suburbs. The president’s strategy was to convince Romney to go away. Romney, who seemed to have gone into government out of a sincere desire to serve, stayed on.

There was a great deal of wrenching irony in this tactic. Nixon had only given Romney the job at HUD — a “liberal” Cabinet agency that had been recently created by a Democratic administration and Congress — to keep him out of the president’s way in the first place. The early “reform”-minded Nixon administration further marginalized Romney by making prominent liberal Daniel Patrick Moynihan the head of the newly created “Council on Urban Affairs,” a panel that appeared to have a policy mandate pretty much identical to that of Romney’s Cabinet agency, but with a more direct line to the president. Nixon didn’t actually care about urban policy or the status of the African-American community. He cared about getting good press, which his feints toward progressive urban policy won him until white communities began resisting — at which point the president no longer had an urban policy to speak of. Romney stayed on in the Cabinet, powerless and ignored, until after Nixon’s 1972 reelection. With a new Nixon team taking shape for the second term, Romney finally resigned, to what must have been the great relief of the president.

“I don’t know what the president believes in,” Romney reportedly told a friend after Nixon effectively told him to stop doing what he’d been explicitly appointed to do. “Maybe he doesn’t believe in anything.”

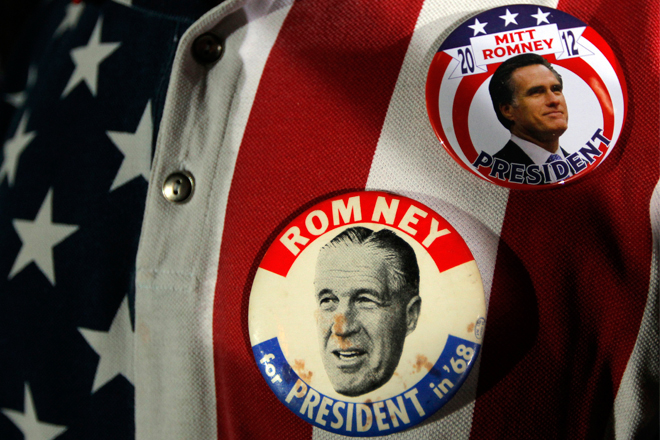

A few years earlier, George Romney had been the front runner for the Republican nomination for president. Romney was probably tied with Nelson Rockefeller as the most preferred candidate of the liberal and moderate Republicans, largely from the Midwest and Northeast, who wanted to regain control of the party following the devastating defeat of conservative Barry Goldwater in 1964. A 1966 New Yorker story declared Romney the leading contender for 1968 — so long as someone didn’t come along who would unite the Republican Party’s warring Goldwater and Rockefeller wings. Someone, the article says, like Richard Nixon.

It’s not hard to imagine that the 21-year-old Mitt Romney, freshly returned from his Mormon mission tour abroad shortly after the 1968 election, noticed that his father, a dedicated public servant with a passion for social justice, lost the nation’s top job to a notoriously unprincipled paranoiac whose main qualification for the presidency was an unchecked willingness to do literally anything to reach it. The guy who didn’t believe in anything won.

And just in case Mitt might have been in danger of missing that grim lesson, his father had driven much the same point home, by negative example, in 1967. The elder Romney had explained to an interviewer that he had come to oppose American involvement in Vietnam after he’d seen the handiwork of U.S. military propagandists painfully contradicted by actual conditions on the ground. The upshot, Romney said, was that he’d received “the greatest brainwashing that anyone can get.”

It was, of course, totally true that military leaders were lying about the war. Whether Romney came to oppose the war for nakedly political reasons or because the veil was legitimately lifted from his eyes, it was still the right call. And making that call destroyed his campaign before New Hampshire even voted.

Romney’s “brainwashing” line went on to become shorthand for a campaign-killing misstep and is an example of how the political press can sink a campaign in an instant. According to Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen, quoted in a 1993 New Yorker piece on Gary Hart: “The press knew that Romney was an idiot, but the question was: How do you write it? So along come his comments about being brainwashed, and — wham! — they take him out. He’s history.”

What lesson did Mitt Romney take from his father’s national humiliation? Certainly not “don’t change your positions.” He seems to have learned something closer to “don’t say what you actually think.”

“It did tell me you have to be very, very careful in your choice of words,” Mitt Romney told the Atlantic in 2005. “The careful selection of words is something I’m more attuned to because Dad fell into that quagmire.”

There you have it: Be careful never to say anything of import and don’t believe in anything, and the presidency could be yours. Or the Republican nomination, at least.

George Romney was a dedicated campaigner when his son Mitt ran for U.S. Senate against Ted Kennedy, but Romney died years before his son won his first (and thus far only) election and subsequently made a series of sharp right turns. George’s paternal pride — his youngest son was a “miracle baby” whom both parents doted on — might have blinded him to his son’s craven mutability. But assuming he could look at the Mitt Romney campaigns of 2008 and 2012 with something approaching objectivity, does anyone imagine he’d like what he sees?

What would the George Romney who walked out on the convention that nominated Barry Goldwater — and who then sent Goldwater a letter accusing him of racism — say about Mitt Romney’s desperate machinations to win the favor of a party now run by Goldwater’s spiritual heirs?

The idea that anti-war, pro-integration upper-Midwest Republican George Romney would even be a Republican in 2012 is preposterous. The man who was too liberal for the Nixon administration would find no room in today’s GOP, where what passes for “moderate” is acknowledging the existence of evolution. (Until his 1994 run, Mitt Romney himself was a registered independent who voted for Democratic Sen. Paul Tsongas.)

Mexican-born George Romney would cringe to see his son promise to veto legislation offering a (still challenging) path to citizenship for people who illegally entered the country as children and went on to graduate from college or serve in the military. The George Romney who fought his own church on civil rights legislation would be appalled to see Mitt Romney accept the endorsement of and make campaign appearances with Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, whose life’s work is crafting legislation designed to make it easier for law enforcement to racially profile Latinos and harass and detain suspected “illegals.” Anti-war George Romney would surely have some qualms with Mitt’s plan to “double Guantanamo.” Hell, George Romney even released 12 years’ worth of his tax returns when a magazine asked him for his most recent one. The full 1040s were made available to the press — at the time, an unprecedented move by a presidential candidates. Mitt Romney, predictably, ignored calls to make public his own tax returns for as long as he could, before releasing only his most recent return.

Whether and where the Romneys differ on specific matters of policy is up for debate and largely a matter for speculation. But there’s no denying that they are very different kinds of politicians. One Romney was on the wrong side of an intraparty war and on the right side of history. He may have been grandstanding and self-righteous — a man with, in the cynical appraisal of the editors of the New Republic in 1964, “an oversimplified, horse-opera sense of morality” — but he was dedicated to his ideals. The other Romney has no obvious ideals, or at least no permanent ones.

In that sense, Romney is perhaps the perfect political fulfillment of the American managerial mind-set: Driven chiefly by an obsession with short-term results and superficial personal likability, the corporate manager in the United States is likewise often forced to contemplate a yawning existential void in the vacant center of his earnest strivings. Other managers-in-crisis will respond to such dark nights of the soul by stoking a midlife crisis, which may or may not involve a sports car, a chronic substance abuse problem and a destructive affair with an underling. But Romney, hostage to both a harshly undeviating commitment to the myth of self-made success and a Mormon worldview that tolerates neither traditional human vices nor the cessation of earnest toil, even after the end of this mortal life, is constitutionally incapable of any such backsliding. Instead, he merely reboots and tackles the next item on his to-do list. (In this case, “be president, no matter what noxious shit you have to say.”)