When I was eleven, my hair began falling out. My grandmother first noticed it. I was visiting my grandparents at their beach house that summer when, one afternoon, she called me over, examined the back of my head, and proclaimed that I had a nickel-sized bald spot. Then we all promptly forgot about it. With the sand, waves, and sun beckoning, it just didn’t seem that important.

But by the time school started a few months later, the bald patch had grown. A dermatologist diagnosed alopecia areata, an autoimmune disorder. My immune system, normally tasked with protecting against invaders, had inexplicably mistaken friend for foe, and attacked my hair follicles. Scientists didn’t know what, exactly, triggered alopecia, but stress was thought to play a role. And at first glance, that made sense. My parents were in the middle of a messy, drawn-out divorce. I was also beginning at a new junior high school that fall; I had, it seemed, much to worry about.

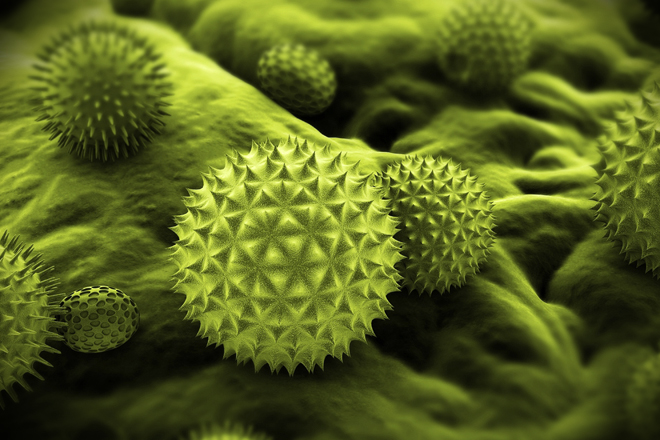

I also had other, better-known immune-mediated problems. I suffered from fairly severe asthma as a child, and food allergies to peanuts, sesame, and eggs. (Only the egg allergy eventually disappeared.) At least once yearly, usually during seasons of high pollen count, my wheezing became so severe that my lips and fingernails turned blue, and my parents had to rush me to the emergency room. There, doctors misted me with bronchodilators, or, during severe attacks, pumped me full of immune-suppressing steroids.

“Aha!” said the dermatologist when he learned of these other conditions. There was a correlation among allergies, asthma, and alopecia, he explained. No one was sure why or what it meant, but having an allergic disease like asthma increased one’s chances of developing alopecia.

Years later, I would learn that the co-occurrence of these two disorders was likely evidence of a single, root malfunction. But at age eleven, I accepted on faith that where one problem arose, so, probably, would others. So what to do? Given my age and the relatively small size of the bald spot, the doctor recommended watching and waiting. Alopecia usually corrected itself in time, he said. So we waited.

In a month, another bald spot appeared, on the right side of my head. Then one on the left. Seemingly overnight, a large one opened up just above the middle of my forehead. As more hairless patches appeared, the pace at which new ones emerged accelerated. Every morning, my mother combed and gelled my hair into place to hide the growing expanse of denuded skin; but soon, concealing my bare scalp became nearly impossible. The spots began to converge. I was going bald.

We returned to the dermatologist. This time, he had a less upbeat assessment. The more the disease progressed, he noted, the less likely recovery. The odds worked like this: Only 1 to 2 percent of the population got alopecia areata at all, a bald spot or two that, after a time, usually filled in again. But for a significant minority, maybe 7 percent of those with alopecia areata, the hair loss became chronic. Some progressed to alopecia totalis, total loss of hair on the head. At that point, the chances of a full recovery diminished substantially. Whatever mistake the immune system had made, it became permanent. And of this totalis subset, some went on to develop alopecia universalis—loss of hair on the entire body. For them, recovery was nearly impossible.

None of this sounded good, especially as I was speeding toward totalis and—who knows?—universalis after that. Two treatment options existed, neither of which worked without fail: immune suppression or irritation. Steroids suppressed the immune response and, basically, called off the attack dogs, allowing hair to grow again. Immune stimulation, on the other hand, worked in slightly more mysterious ways. Inflammation induced by an irritant distracted the immune system from less pressing projects, such as attacking hair follicles. Irritation would earn my hair follicles a reprieve. As neither approach was a sure bet, the dermatologist recommended that I try both.

I did, and neither worked—although I developed an oozing blister where I applied the irritant. My alopecia advanced until, by age sixteen, not a single hair remained on my body. I had joined the elite ranks, somewhere around 0.1 percent of the population, of those with alopecia universalis. I put on a hat, which I’d wear more or less nonstop until my early twenties, and tried to get on with my adolescence.

– – – – – – – – – –

Not until my thirties did I look into what scientists had discovered in the roughly twenty years since that first bald spot appeared on my head. I wasn’t too hopeful; surely, I would have heard had a cure been developed. As I contemplated having children, I’d begun fretting about what lay hidden in my genes. The first genome-wide association study of alopecia, published in 2010, showed that the disorder, the most common autoimmune disease in the U.S., shared gene variants with several much worse autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, type-1 diabetes, and celiac disease. Soon thereafter, my first child, a girl, arrived. Now the results of my investigation had concrete applications. If alopecia suggested a tendency toward immune malfunction, and if that tendency was modifiable, I wanted to know how to better play the cards. I wanted to ensure that my progeny remained free of both allergic and autoimmune disease.

I was right about one thing. Treatments for alopecia hadn’t advanced much since my childhood. They still consisted mainly of irritants and immune suppressants, and as neither approach corrected the underlying malfunction, both would require indefinite use. Prolonged exposure raised a host of secondary concerns. Repeated steroid shots, for example, were not only exceptionally painful, they thinned and discolored the skin. Irritants induced swelling, redness, and skin flaking. One powerful immune suppressant called cyclosporine increased the risk of skin cancer. No thanks.

Excerpted from “An Epidemic of Absence: A New Way of Understanding Allergies and Autoimmune Diseases,” by Moises Velasquez-Manoff. Copyright © 2012 by Moises Velasquez-Manoff. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.