Tomorrow night, millions of Americans will tune in to the first presidential debate of the 2012 campaign. The 21st century voter has a multitude of media to see and hear the debates in real time: TV, streaming online video, radio, and even “live-GIF.” But before the United States was awash in broadcast signals and Internet tubes, voters had far fewer options to learn about the candidates for president and what they stood for. But with the presidential election of 1924, American politics would be thrust into the future with a little help from a newcomer called radio.

Tomorrow night, millions of Americans will tune in to the first presidential debate of the 2012 campaign. The 21st century voter has a multitude of media to see and hear the debates in real time: TV, streaming online video, radio, and even “live-GIF.” But before the United States was awash in broadcast signals and Internet tubes, voters had far fewer options to learn about the candidates for president and what they stood for. But with the presidential election of 1924, American politics would be thrust into the future with a little help from a newcomer called radio.

Radio was still a young platform in the early 1920s. Radio sets were expensive, with typical units costing between $50 and $150 (about $600 to $1,900, adjusted for inflation). Radio sales were on the rise, but in 1924 only about 10 percent of U.S. households had a radio receiver.

Although the audience was incredibly small by today’s broadcast standards, no other medium allowed the two major parties’ candidate to speak, with their own voices, to Americans directly in their homes. The 1924 election educated both major parties, showcasing the power of broadcast and launching Americans into a brave new world of soundbite politics.

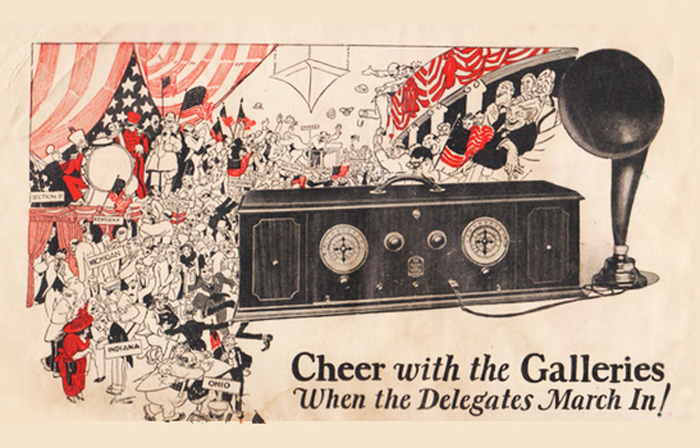

The July 1924 issue of Radio News magazine included the ad above for a Radiola brand radio receiver, made by the Radio Corporation of America. The radio was still expensive by the standards of the day but could be purchased with a down payment and paid off over the course of a year. Radio was seen as a democratizing force from very early on. This ad explained that the arrival of this new medium meant politics was “for everybody” rather than just “the big folks,” ad copy that prefigures today’s talk of the 99 percent.

From the 1924 Radiola ad:

No “influence” needed this year for a gallery seat at the big political conventions! Get it all with a Radiola Super-Heterodyne.

When the delegates march in—their banners streaming; when the bands play and the galleries cheer—be there with the “Super-Het.” Hear the pros and cons as they fight their way to a “platform” for you. Hear the speeches for the “favorite sons.” The sudden stillness when the voice of a great speaker rings out. The stamp and whistle and shrill of competitive cheering. Hear the actual nomination of a president.

It used to be all of the delegates’ wives and the “big” folks of politics. Now it’s for everybody. Listen in. Get it all! With the newest Radiola.

Before 1924 the nomination of a presidential candidate was essentially seen as a private affair for the respective parties—with a certain amount of print coverage, of course. But the decision to broadcast the conventions was definitely a learning experience for the Democrats who struggled to nominate a candidate on live radio—taking an excruciating 103 ballots with brutal infighting to nominate their eventual nominee, John W. Davis. The Republicans were ahead of the Democrats every step of the way, using radio much more effectively during the 1924 campaign.

As David G. Clark notes in his 1962 paper on early radio political campaigns, the Republicans opened up an office at 2 West 46th Street in New York on October 21, 1924, in order to broadcast their message on a dedicated station. They would broadcast all day, every day until election day. However, their programming wasn’t quite what might be expected when compared with the polished and media-savvy campaigns of the decades that would follow. Some titles of the Republican speeches included, “The Foundations of the Constitution” and “The Vicissitudes of a Practical Politician.” Nonetheless, the Grand Old Party rode to victory, electing Calvin Coolidge in 1924.

Perhaps one of the most prophetic observations came from an internalRepublican memo about what they’d learned while campaigning over radio: “broadcasting requires a new type of sentence. Its language is not that of the platform orator… Speeches must be short. Ten minutes is a limit and five minutes is better.”