In our day-to-day lives, and to our great good fortune, people do not just burst into song and dance. There are exceptions to this, maybe—wrong turn into a theater camp; some nightmare struck-by-lightning flashmob scenario—but by and large they do not, and certainly they shouldn’t. This, or this and the horror of other people singing and dancing and so vigorously emoting their emotions, is why musicals are so rough for me.

In our day-to-day lives, and to our great good fortune, people do not just burst into song and dance. There are exceptions to this, maybe—wrong turn into a theater camp; some nightmare struck-by-lightning flashmob scenario—but by and large they do not, and certainly they shouldn’t. This, or this and the horror of other people singing and dancing and so vigorously emoting their emotions, is why musicals are so rough for me.

“Rough” is, honestly, maybe understating it. I cringe at the dramatic sliding and stomping around the stage, the emphatic rhythmic speech slyly turning into a melody, and then into a song that infects innocent bystanders who magically chime in, in perfect synchrony. The transition from daily life to song and dance is the musical’s central conceit, but it also feels like a clumsy trick, an uncommonly dorky hustle. I was watching, after all. Everything was normal and then, out of the blue, there’s the eruption of choreographed/chaotic collective delusion. This is maybe not the bravest of stances, but I won’t be part of it.

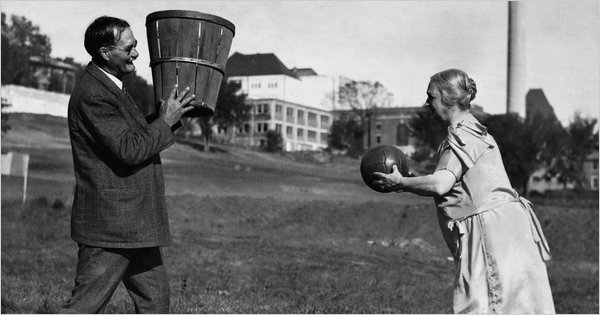

Basketball, on the other hand, has its own rituals and artificialities and weird rituals, and I will sit through pretty much anything basketball-related. So what to make, then, of the existence of a musical about the invention of basketball? Initially, not much: I’ve read too much idealizing lore about the invention of basketball, too much nostalgic fantasy. So taking the story of James Naismith—the game’s patron saint and founding father and so obviously on—and making it a musical made a certain sort of sense. Of coursesomeone adapted this particular basketball myth into the squarest of artistic forms. It’s not promising on its face, but there’s something to it: what could better express the hyper-romanticized and sentimentalized drama permeating the various narratives of the game’s invention than a musical? Here, it seems, is a perfect target for an archly ironic critique of the purist dream of basketball’s pristine origins. Whether the musical itself would be in on that critique was a different question entirely.

* * *

Written, directed, and produced by John Grissmer, The Perfect Game: Jim Naismith Invents Basketballshuttles back and forth in time between 1891 and the present. In the present, “The Home Team” prepares for the big game against “Arch Rival,” as a love story develops between the home team’s young interim coach, Frank, and ex-coach Nancy, the former women’s basketball coach who resigned her post and is reassigned to lead the pom-pom squad. Meanwhile, in 1891, Naismith meets and courts his wife to be, Maud.

Naismith himself, aged 31 (as he actually was when he invented basketball in December, 1891) appears to Nancy in the present and takes on a mentoring role: helping her work through and overcome her fraught feelings about coaching and Frank. Meanwhile, at different points in the story, both Nancy and Maud discuss with Naismith aspects of the development of the game subsequent to its invention, in particular the relative importance in basketball of recreation and winning.

Amidst the developing romances, the hype leading up to the “big game,” and the discussions about the evolution of basketball, Grissmer includes several scenes depicting the events leading up to Naismith’s invention of the game. Thus, we see Naismith in a seminar on psychology, claiming that rational, modern principles of invention should be applied to the invention of new games; we see the class of “incorrigible” students complainingly going through their dull gymnastic routines; we see Naismith alone thinking and imagining his way to the new game with its 13 original rules; and we see the unruly class try the game out and take to it immediately. Much of this material recapitulates the story as both historians and Naismith himself, toward the end of his life, recounted it.

Much of it, I say, but not quite all of it. For, despite all the ample evidence to the contrary, including Naismith’s own story of how dribbling emerged accidentally and only in time became a fundamental art of basketball, Grissmer stubbornly insists on portraying Naismith conceiving of the dribble in its modern form as a critical missing piece to the puzzle of his new game.

The ball. (BEAT) The ball will have to be large and light. (BEAT BEAT) So as not to cause injuries. (BEAT) Movement and speed, any direction. No running with the ball. No carrying it against the body. (BEAT) No tackling. No punching the ball. (BEAT BEAT) Pass the ball. Allow an extra step for stopping from a run. (BEAT BEAT BEAT) Pass the ball or bounce it off the floor.

(SOUND STOPS)

Bounce it off the floor? (BEAT) Well, why not? Bounce the ball at a flat angle off the floor to another player. Or – that’s a funny idea – the player could bounce the ball to himself. Hah!

The relative quality of those lyrics aside, that is all fully false. So naturally The Perfect Gamemakes the dribble into the keystone of its version of the game’s invention and subsequent evolution. Thus, in a scene portraying Naismith’s initial encounter with his soon-to-be wife Maud in 1892, a flirtation arises as Naismith demonstrates the dribble, Maud practices it, and then Naismith playfully steals the ball as Maud equally playfully uses her body to protect the ball from his reach, slamming “her butt into him. Hard,” as the stage directions indicate. This happens while the two bust into a duet called “The Dribble.”

Finally, toward the end of the work, as Maud and Jim, now married and looking back at their lives together and at the role of basketball in them, tensions that arise between them as to the value of the game are resolved when James recalls that very first game of basketball in December 1891, and specifically how he instructed the players in the dribble. In Grissmer’s version of the story Naismith’s conscious invention of the dribble becomes both the key Jim and Maud’s winning love story and the catapult for basketball’s worldwide popularity.

Which is okay for the show’s purposes, but which makes it more difficult for me to stay out of all this. This falsification of history serves to secure an essential continuity between the game Naismith conceived and the game as it is played today. I’ll go one step further and speculate that this reveals, even as it strives to calm, some anxious questions about the game’s evolution. Has the game strayed too far from its origins? Has winning become too important? Has the game’s popularity, and the media attention and money that it attracted and that have in turned further fueled that popularity, irreversibly distorted the purity of the original game? Maybe more to the point: are these questions even interesting to you?

* * *

If today’s game is so dramatically different from what Naismith invented, is it still basketball? Or, more alarmingly, if today’s game is basketball, then what the hell do we call what Naismith invented? This is the tricky part: the challenge of what to do, at a deeper affective level, with the scandalous tragedy that things change, that time and the world irresistibly transform the things we love. Having Naismith invent the dribble provides the comforting fantasy that things maybe aren’t so different after all; that some things endure, remain pure and true to original intentions.

There are many good reasons to explore a little more forcefully this critique of anxiety-ridden myths of basketball’s origins, myths which depend upon and try to purvey as truth a belief in basketball having a single, fixed essence, invented a century-and-some ago by a particularly ingenious gym teacher. But there’s no need to blow that up, really: it’s mostly false on its face, and as unconvincing as any other similarly essentialist argument.

Instead, despite my critical reservations about Grissmer’s fantasy and others like it, and about the medium he chose, I find myself in another argument. I can’t stand musicals; I can’t stand silly sentimentality about the halcyon past of a sport so alive in the present. But I still find myself wanting to celebrate the existence of this musical and the love of the game that Grissmer expresses through it. It’s okay that the basketball Grissmer cherishes and preserves isn’t the same basketball that I love. It’s even okay that the basketball he imagines never really existed. What’s important is that in creating his musical—and laboring for years against all odds to have it produced—Grissmer was feeling and trying to transmit the same spark of life in the game that I and everyone else who writes about this sport wants to convey in our words about basketball. There’s truth, and then there’s truth.

***

And this is what basketball can inspire: affective intensities so powerful that they can impel a middle-aged and mostly unknown playwright to dedicate years of his life to a fantastic portrayal of the game’s origin. Despite our differences in point of view, I can’t help but feel empathy and tenderness for—can’t help but identify with—the intensity of attachment to something in basketball that apparently drove Grissmer to create his musical. It’s not so different, really, from what makes any of us write about basketball; it’s there on the page in the Why We Watch series, and even in the odd awestruck Tweets that follow a particularly virtuosic Chris Paul moment.

And there is, maybe, a way in which basketball and musicals have some things in common. Both involve unembarrassed exaggerations of aspects of daily life; both generate over-the-top drama and complexity from the constraining matrix of simple elements, rules, and formulas. In this sense, the composer and the point guard have some strange thing in common. And both musicals and basketball invite us to suspend our critical judgment and to be taken in by a spectacle so that our emotions will be stirred, drawn forth, and expressed. This happens on the court, if we’re being honest, in just as eruptive and chaotic a manner as it does on the stage.

What’s more, the boy in me whose first discovery of the powers of the game as a player involved dribbling can’t help but feel that there is a truth in Grissmer’s lie; the dribble isthe key to the game, after all, even if the game’s inventor didn’t discover as much. But this goes beyond my own love of the dribble. The dribble is the key to the game also for reasons relating to the true history of basketball that Grissmer elides in his musical.

The dribble—today a practiced fundamental skill, a tactical maneuver, a much admired form of artistic expression in the game, and actual percussive music itself in that ubiquitous NBA Store/”Carol of the Bells” commercial—was neverimagined, let alone expected or planned. It just happened and from there grew rapidly through myriad contingent factors into what it is today, what it is still becoming.

Or rather, more precisely, a player’s body responded to an intractable and seemingly insoluble problem encountered in the course of play—being trapped in a corner with the ball, surrounded by defenders, prohibited from running with it and unable to pass it successfully—by breaking the rules, and so inverting the game. The debates about legality and desirability of dribbling come later. So also do the formalization of the dribble and the reasoned calculation about how to do it best and most effectively.

What’s important is that in an instant, a player’s body reflexively reinvented the game; that, and that the game then accepted and assimilated that foreign body. It’s hard to think of a more apt emblem for the life in basketball and how it works to free itself from what imprisons it. And yet, at the same time, when you see the game through these eyes, you see that every single game of basketball, every single play entails, at least on the micro level, myriad reinventions of the game; myriad exhibitions of a body, in an instant of time, adapting itself and its circumstances into the shape of something we’ve not yet seen.

The life in basketball is a kaleidoscope, an ocean wave, a flame; ceaselessly becoming, like the first player to dribble; ceaselessly freeing itself from what would imprison it. And so, in the end, maybe actually rather like the song and dance that bursts forth from the stiff constraints of daily life in a musical.