Top-10 lists are an annual ritual for most critics, typically approached with wariness — so much reading, listening or viewing to catch up on, so many opportunities to blow it! By the time our fellow critics’ lists come out, our interest, though keen, has become largely academic and quibbly. Did he really love that book? Didn’t she think the last half of that film took a nose dive into bathos? How could so-and-so leave out such-and-such?

All of which is to say that we critics don’t read these lists the way you do — not, that is, unless you also compulsively check them against your own personal pantheon and then curse yourself for not skipping sleep for a week to make time to read the new Robert Caro. These days, most readers mulling over which book to pick up next regard year-end lists the way they regard book reviews themselves: It takes several persuasive recommendations before they’ll give a book a shot. Everyone feels they have less time for reading than ever before, so they want to be as confident as possible about the books they spend it on.

The notion behind the column What to Read is that when the same critic recommends a title each week, explaining what makes it exceptional, readers get the opportunity to gauge her taste against their own and proceed accordingly. The most acted-upon book recommendations, after all, come from a trusted friend (or a friend whose bizarre penchant for, say, cat detectives you can take into account when weighing her suggestions). This year, however, What to Read presents almost 20 critics’ verdicts on the year’s best books, ratings that have been carefully weighted and crunched to produce an aggregate opinion. (If you want to see my own old-school top-10 list, it’s here.)

Perhaps the most striking thing about these results is the prominence of “Behind the Beautiful Forevers” by Katherine Boo. This, with the also-strong showing by Andrew Solomon’s “Far From the Tree” — a book that would, I believe, have ranked even higher if it weren’t so darn long; many critics simply haven’t found time yet to read it — is all the more remarkable because book critics routinely privilege fiction over nonfiction. Several of the lists Salon collected feature only one or two nonfiction titles, and many of those are memoirs, often regarded as an easy-to-read variant on the autobiographical first novel.

This is where book critics differ from much of the reading public. Fiction remains popular, but its bestseller lists teem with entertaining but otherwise disposable airport thrillers; it is to nonfiction that America’s readers turn when they want something more serious, substantive or insightful, from social commentary to presidential biography. Critics put two Iraq War novels (“The Yellow Birds” and “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk”) at the top of their lists, for example, but readers much preferred Navy SEAL Mark Owen’s firsthand account of the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, “No Easy Day.”

We live in a golden age of nonfiction, largely because this is also an age preoccupied with questions of the truth — how can we arrive at a version of it on which (almost) everyone agrees? Both “Behind the Beautiful Forevers” and “Far From the Tree” evince the belief that a writer who utterly immerses herself in a subject and strives to record what she sees as faithfully as possible will get us the closest to that precious standard. Each of these books is a heroic work of reporting. But if you’re interested in problematizing the very idea of truth, nonfiction can do that, too. I didn’t much like John D’Agata and Jim Fingal’s “The Lifespan of a Fact,” chosen by one of our guest critics, but it’s a stab in the right direction, and to my mind Errol Morris’ “Wilderness of Error” raises, in microcosm, questions no thinking member of our highly mediated society can afford to ignore.

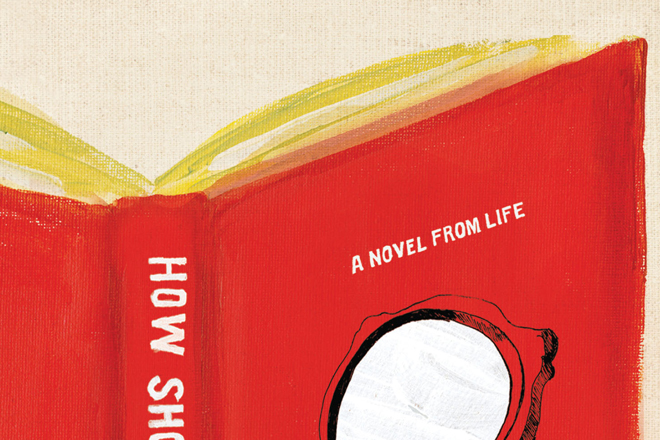

For the most part — and perhaps understandably, given the fact that it’s made up — contemporary fiction avoids this issue, whether by focusing on the micropersonal, like Sheila Heti’s “How Should a Person Be?” or by making an almost nostalgic return to the subjective modernism of Virginia Woolf, as Zadie Smith does in “NW” — both fine novels and popular with our critics. Nevertheless, the two highest-rated novels on this aggregate list, “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk” by Ben Fountain and “Bring Up the Bodies” by Hillary Mantel, take the nature of political truth as their subject. Fountain juxtaposes the jingoistic story civilians told themselves about the war in Iraq against the experience of a soldier who actually fought in the war, and Mantel writes against one of the most widely accepted narratives of English history.

Because writing fiction so often amounts to coming up with a convincing (though fabricated) story, novelists are more relevant to today’s endlessly fascinating quest for truth than we acknowledge. Critics, too, believe it or not. Is it even possible to determine the best books published in a given year, since even if we could settle on a shared standard of excellence, no one person could possibly read them all? We seem to alternate between a naive faith in critical consensus — even if it mostly comes in the form of ranting about the critics who violate that faith by disagreeing with us — and shoulder-shrugging deferral to the mysteries of average Amazon rankings and tastes that cannot be accounted for. Where can we hope to find an answer to such a question: In the idiosyncrasies of the individual mind, however familiar, or in the wisdom of crowds, even when they’re made up of strangers?

There’s a happy medium between the two, no doubt, — and good luck finding it! In the meantime, here are many excellent and provocative lists of possible choices. One thing you can be sure of, when you finally decide on that next book and sit down to read its first page: There will be a voice there, one author, speaking to you, one reader. At that point, how good a book it is will no longer be a question for critics or prize juries or other people who bought similar titles. It will be up to two people and two people only, alone and together at the same time.