Joan Didion. The name alone conjures up an ocean of descriptive phrases in which one could drown. Here is but a small helping: In Salon, Kyle Minor called her “the most consistently interesting and quotable essayist in the English language.” InIntelligent Life magazine, Robert Butler echoes that sentiment, labeling her first-person voice “cool” and “incisive.” “The writer who expressed most eloquently the eternal-girl impulse,” Caitlin Flanagan recently dubbed Didion in The Atlantic. A visit to the Amazon page of but one of her fourteen books yields “taut, clear-eyed,” “extraordinarily poignant,” “achingly beautiful,” and, about the book peddled at this particular URL, “a remarkably lucid and ennobling anatomy of grief.”

Joan Didion. The name alone conjures up an ocean of descriptive phrases in which one could drown. Here is but a small helping: In Salon, Kyle Minor called her “the most consistently interesting and quotable essayist in the English language.” InIntelligent Life magazine, Robert Butler echoes that sentiment, labeling her first-person voice “cool” and “incisive.” “The writer who expressed most eloquently the eternal-girl impulse,” Caitlin Flanagan recently dubbed Didion in The Atlantic. A visit to the Amazon page of but one of her fourteen books yields “taut, clear-eyed,” “extraordinarily poignant,” “achingly beautiful,” and, about the book peddled at this particular URL, “a remarkably lucid and ennobling anatomy of grief.”

But goodbye to all that, for now.

That last sampling of accolades is, of course, relevant to Didion’s 2006 bestseller The Year of Magical Thinking, which is—it feels almost patronizing to rehash—about the death of her husband of a wee-bit-less-than forty years, the writer John Gregory Dunne, who collapsed in their living room after a massive heart attack. The book won the National Book Award for nonfiction, was a finalist for a Pulitzer and a National Book Critics Circle Award, and was the basis for a play of the same name, which opened on Broadway starring Vanessa Redgrave in 2007. Magical Thinking described a marriage based on such intense personal attachment and perfect Pacific Coast beauty that the book has been met with some disapproval from critics and readers alike. Based on the book, however, one thing about their life together is indisputable: Dunne and Didion adored each other, and managed to do so up until the very end, despite the fact that, because of the nature of their professions, it would have been very easy to fall into the wormhole of competition.

Though Dunne was always the less successful of the two, he has become increasingly less of interest in the past few years. Part of this is the nature of death, and another part is that the last and most famous role he played was as negative space in his widow’s memoir. For a generation of readers, therefore, it is easy to imagine that the most important thing John Gregory Dunne ever did was die on Joan Didion. For us, he was never there—but then his absence was of immediate emotional enormity. He was a being whose most incentivizing move was to step off camera.

If we know of him at all, it’s of his position as second fiddle, as Prince Philip to Joan’s Queen Elizabeth in the “first family of angst,” as the Saturday Evening Post dubbed them. Those of us who have at some point hung on Didion’s every word, who “received from her a way of being female and being writers that no one else could give,” (Flanagan again), maybe catalogued a few facts about him from Didion’s elegy, but only because they were a part of Didion’s marital life, and not because they belonged to a separate individual. We may remember, for instance, that he carried index cards in his pockets on which to write notes for books, or that he used bits of his daughter’s charming child-patois in novels. We definitely remember the comic image of Dunne reading Sophie’s Choice standing in the pool at their house. He also, we know, collaborated with Didion on five screenplays that were made into uniformly mediocre movies, the one exception—a big one, maybe—being the dreary and dated film-length PSA on heroin addiction, The Panic in Needle Park.

✖

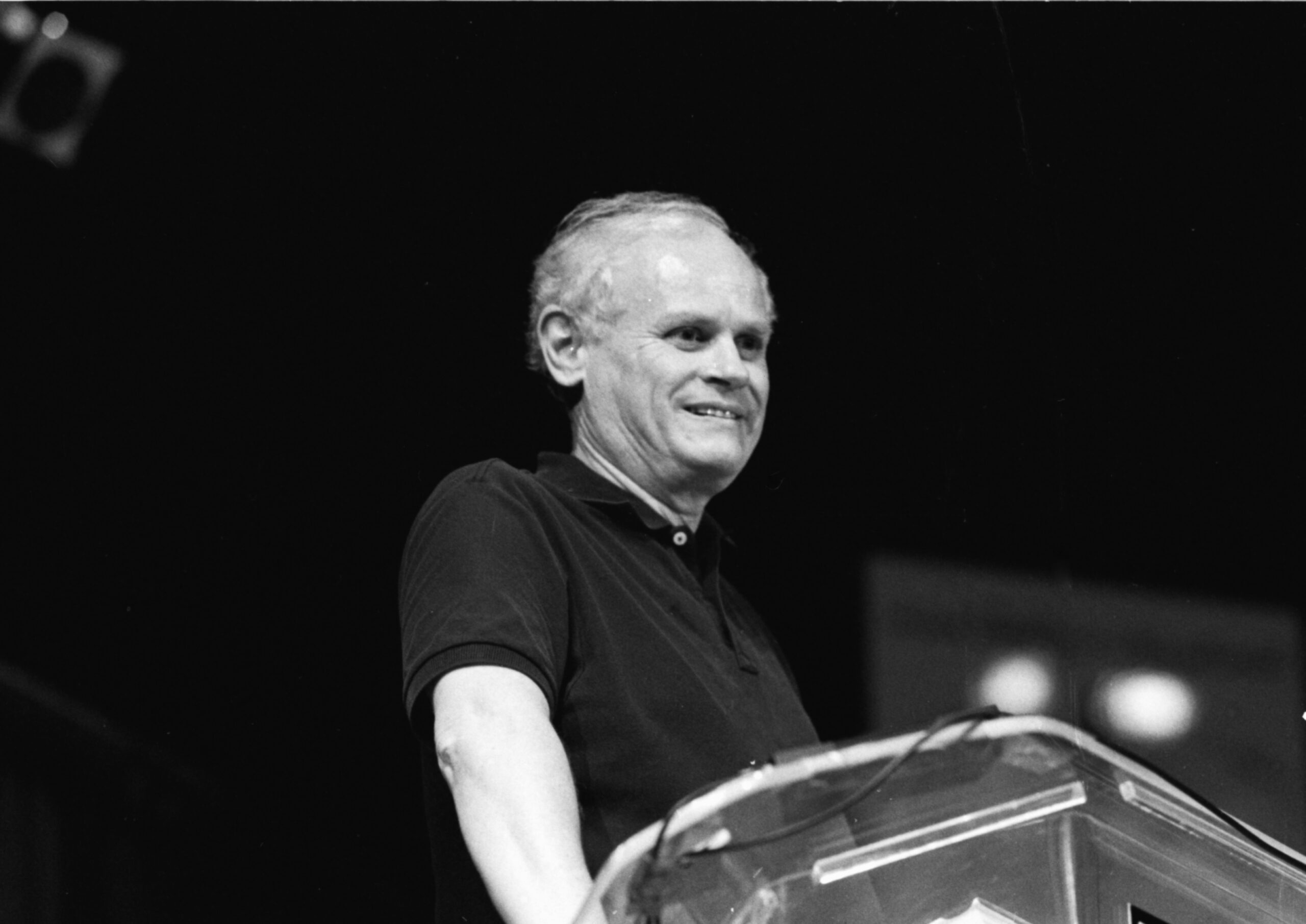

John Gregory Dunne—Hartford born, Princeton educated, Hollywood obsessed—was the author of thirteen books published between the years 1967 and 2006. Like Didion, Dunne didn’t stick to one genre but wrote both fiction and nonfiction equally, sometimes even—most notably in Vegas and Harp—blending fiction and reportage into bastardized memoirs that foresaw modern works by Sheila Heti and Dave Eggers. His first book, Delano, is perhaps the most fascinating of his nonfiction in that it captures a very specific historical phenomenon: the California Grape Strike of 1965. Perhaps Dunne’s greatest achievement here was recognizing that a story existed within the discontented rumblings of migrant workers out in the arid Great Central Valley of Southern California. In the essay “Ex Post Facto,” reprinted in the 1979 collection Quintana and Friends, he tells of pitching the story to editors all over New York, only to be summarily rebuffed.

“‘Who the hell has ever heard of Cesar Chavez?’ asked one editor who has since nominated him for sainthood.”

But Dunne, whose tenacity emanates from the pages of even his most placid prose, persevered; he knew that the elements of a good drama—a group of poor, put-upon little guys going up against fat cat farm owners—were there for the writer’s taking in this story, and he was right. The lenient editors at the Saturday Evening Post gave him the green light to write an article, which eventually morphed into Delano. Cesar Chavez, the soft-spoken spiritual leader of the then-nascent National Farm Workers Association, was the perfect protagonist, and Dunne skillfully captures the kind, weary aura of a man taking upon his shoulders the misery of an entire community. Dunne also manages, in quick brushstrokes, to paint a picture of the various other people and groups on the Delano scene, and of these there are many. There are jejune hippies and SDS members bused in from San Francisco to bolster picket lines; silent, abused Mexicans and Filipinos who picked grapes beneath the searing sun for an hourly wage of less than $2; Yugoslavian growers, themselves the descendants of immigrants, who hang out at the town’s Slav Hall; the Citizens for Facts, run by a group of concerned “Anglo” housewives, which comes across as a more sinister and venomous Daughters of the American Revolution; and the Johnny-Come-Lately Teamsters, who stay at the Stardust Motel and spend their days drinking beer and tossing around racial epithets.

By its conclusion, the story becomes messy and tiresome, with all the endless groupings and ruptures and regroupings, but none of this is Dunne’s fault. He retains his grasp as best he can, especially on the individual characters. He nails the ethereal power of Chavez and, in the aforementioned essay “Memento Delano,” about his return to Delano years after the book’s completion, he prophesies what will become of him. “For all the wrong reasons, Chavez had all the right credentials—mysticism, nonviolence, the nobility of the soul,” Dunne writes. “But distastefully implicit in instant apotheosis is the notion of causes lost; saints generally fail and when they do not, the constant scrutiny of public attention causes a certain moral devaluation.” While it’s unclear that the attention lauded on the NFWA was the ultimate corrupter of Chavez and his group, Dunne was correct in thinking that the entire organization would eventually meet an unseemly end. (The death knell was the 2011 book on the myriad wrongdoings of Chavez and co. authored by Los Angeles Timeswriter Miriam Pawel.)

✖

Over the course of writing this article, I stumbled across a reader review for Delano that accused Dunne of impassiveness toward his subjects. Though Dunne does cast himself in an unflattering light when he interrupts the flow of the story to announce he’s headed to Hawaii for ten days to escape all the “bitterness” in Delano, for the most part, the book reads like straight journalism, and Dunne himself plays a very small role in the actual plot of the book. (His other half is mentioned only once, and it’s a vague mention at that. “And that little lady with you in the red dress—was that your wife?” a town sergeant inquires.) Dunne’s absence is a kind of blessing, because in his nonfiction to come, he’s going to be enormously present, and as a narrator, he’s not always likable, but rather at turns gruff, pompous, elitist, and self-indulgent. His style is aggressive, and yet one gets the distinct sense that he’s never been in a realfight. He’s the teetotaler who hangs out in biker bars just to watch others live hard and fast.

Perhaps nowhere does his writerly persona grate more than in Vegas, his fictionalized memoir of the time he spent in Vegas post-nervous breakdown. (As far as I can garner, the Didion-Dunne contingent believe a nervous breakdown to consist of nothing more than a spat of vertigo and/or a penchant for driving way over the speed limit on the highway, which hardly passes muster as far as artistic collapses go.) Vegasopens with a series of humiliating scenes, including Dunne giving a sperm sample while fantasizing about a nun, being beaten up by a teenage cowboy on the side of the road, and phoning a prostitute whose services he used some thirty years prior. It’s pretty much downhill from there, except less for him than for those he admittedly follows around for the sake of material. There’s Artha, the prostitute who keeps a record of the various things she’s been asked to do on the job (863 blow jobs in five years) and yet writes decent poems on the back of cocktail napkins. There’s Buster Mano, the private detective obsessed with his digestive tract. And there is the saddest creature of the lot, Jackie Kasey, the B-list lounge comic banking on a new, laughable—in the bad way—comedic persona to get the attention of William Morris agents or Bill Cosby or basically anyone.

These three characters have nothing in common, so it stands to reason that Dunne sought “them” out because he wanted seedy characters on whom to capitalize. (It’s “them” with the quotations as the book begins with a caveat about how the hooker, the comic, and the PI are real Vegas characters, but these specific people don’t exist.) Dunne brings up the fact that he’s consciously using these people so often that it’s like he wants to remind the reader repeatedly of the lecherous way he views those around him. “The instinct of the reporter takes over and with it the malignant knowledge that disaster is always good copy,” he writes, and it would seem he means disaster in a large sense or in the tiny, personal one. The book has no plot to speak of, and, while punctuated with moments of seriously absurd hilarity, it ends with an inevitable whimper: “I can offer no guarantee that everything you read actually happened, only that insofar as it was perceived by my fractured sensors it was true. Then the pieces were back together, and in the fall I went home.”

The bulk of Dunne’s writing, though, lies in that middle area in which he is present but reined in by the construct of fiction or the rules of nonfiction writing. In his straight fiction, he can use his predilection for stock crime-fiction characters—street-wise cops, disillusioned priests, hookers who meet hard ends—because they serve the plot; they belong to the world in which Dunne has placed them, and so the reader doesn’t feel the urge to dislike all parties involved so much. Dunne uses these personalities very well in True Confessions, his novel about the infamous Black Dahlia murder case, which nearly transcends its status as genre literature because the writing is so clear and controlled. (It doesn’t reach that height because Dunne doesn’t break any noir traditions, nor does it seem he would care to.) In his nonfiction, you can forgive his incessant name-dropping, romanticizing of the Californian lifestyle and landscape, and undeniable glee at skewering a Hollywood he so clearly adores because it’s the truth. Also, not all of his essays he treats as arenas for such displays of self-adoration. Some of them, namely “Nevermore, Quoth the Eagle,” about the IRS and laundry, and “Fractures,” about when he broke his elbow, are pretty damn funny, which is one thing he’s got on Didion’s generally humorless pieces. Only a choice few pieces reveal any emotional vulnerability on Dunne’s part, but the ones that do are simply heartbreaking. I’m thinking specifically here of “Friends,” the essay about his friend Josh Greenfield’s autistic son Noah and the book Greenfield wrote about raising a son with “genetic rot” (Greenfield’s words, not mine, or Dunne’s). Dunne seems so loving and reverent of strange, babbling, misunderstood little Noah, and his ability to see and absorb the pain of his dear friend is quite extraordinary, particularly given that at the time the essay was written, autism was not always approached in the gentle way it is presently.

While exploring Dunne’s oeuvre, it can be difficult to not look for Didion between the lines. When you allow yourself to see her, though, she is suddenly everywhere, and then again, when you go back to her work, you see him peppered throughout, and then it is impossible to cleave them apart. It is true that Dunne calls attention to his wife’s presence far more often in his work than Didion mentions him in hers, of course with the exception of Magical Thinking. This could be indicative of Dunne’s love for and reliance on Didion, his desire to mention her name for publicity’s sake, or neither. But it’s also true that their prose styles and favored subjects, over the years, began in many ways to resemble one another in a pattern that’s completely undecipherable. Which of them developed the taste for the absurd first? Who began to write in triplet phrases? Who initially heard the story of the man who went out into the Death Valley desert to speak to God and instead met his end by snakebite, an anecdote both Dunne (in the essay “Eureka!”) and Didion (in Play It as It Lays) use in their writing? Had Dunne outlived Didion, would he have written a book about his own grieving process? Theirs is the literary version of the long-married couple that begins to look alike—or did they always resemble each other, drawn together by their individual reflections in the mirror of their beloved?