Two decades have passed since I began my gradual and reluctant break with the conservative movement, in which I had been a protégé of the late William F. Buckley Jr. and an employee of the late Irving Kristol, as executive editor of The National Interest. Since then, I have been followed by, among others, Andrew Sullivan, Fareed Zakaria, Francis Fukuyama, David Frum and Bruce Bartlett, all of whom, for different reasons and at different times, have become estranged from the American right. Of the British Labour politician Tony Benn, a young conservative who moved leftward over time, Harold Wilson sneered, “He immatures with age.” Others may judge whether I have immatured with age. In thinking about my career, first on the right and then (to quote FDR) “slightly left of center,” I think I have been consistent in opposing utopianism in politics, something once characteristic of part of the left and now the defining quality of the contemporary American right.

In the age of Barack Obama, who would have been considered a moderate conservative a generation ago, it is easily forgotten that there was a radical left that was really radical — and not in a good way. As late as the 1980s, a classmate of mine at Yale insisted that Lenin was a noble fellow who was betrayed by Stalin (we now know that Lenin invented the Soviet system of secret police, torture and judicial murder). Another classmate told me that a Yale professor had denounced Poland’s General Jaruzelski, who imposed martial law on communist Poland in 1981, as a bourgeois deviationist who was insufficiently Stalinist. In those days Marxists were not limited to friendly, decent “democratic socialists” who were indistinguishable from welfare-state liberals; there was a dwindling minority of hardcore leftists who saw the Soviet Union or Castro’s Cuba as a flawed model of the future socialist order that would soon emerge from the breakdown of Western capitalism. As it happened, Western capitalism did break down partly in 2008, but by that time nobody any longer thought that models could be found in communism, which had finally been discredited two decades earlier.

Today we think of anti-government militants in terms of white supremacist conservatives. It is worth recalling that the 1960s and the 1970s witnessed the Black Panthers, the Symbionese Liberation Army that kidnapped and brainwashed Patty Hearst, and Europe’s murderous Baader-Meinhof gang. Before the cult of gun ownership became identified with the far right, there was a far left that idolized communist revolutionaries like Che and was fond of quoting the mass murderer Mao: “Power grows from the barrel of a gun.”

Needless to say, such radicals made up a tiny minority compared to the overwhelming numbers of moderate liberals in the U.S. a couple of decades ago. The problem was that the New Deal liberals of the 1970s and 1980s were as intellectually bankrupt and demoralized as the dwindling remnant of moderate Republicans today. There were aging political warhorses like House Speakers Tip O’Neill and Jim Wright, but no younger intellectuals in the New Deal tradition had acquired the influence of those of the older generation, like John Kenneth Galbraith and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. The radical left tended to pull left-of-center discourse in its direction a generation ago, in the same way that Tea Party militants define today’s right, even though they are outnumbered by less radical Republican voters.

In that environment, what attracted me in my college years to conservatism was its hostility to utopianism, to the attempt to remake society according to some abstract theory. This was a theme shared by the older generation of “vital center” liberals like Arthur Schlesinger and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, as well as conservatives like Bill Buckley. Their distrust of doctrinaires using power to achieve utopia on earth was inspired not just by thinkers like Edmund Burke but even more by the examples of Hitler’s genocidal racist utopia and the mass murders and famines that accompanied Stalin’s and Mao’s attempts to use terror to remake society. The vital-center liberals (some of whom became early neoconservatives) disagreed with those further to the right, the “paleoconservatives,” over whether Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society were examples of sensible reform to save the system, as the paleoliberals/neoconservatives believed, or mild versions of collectivist utopian madness, the view of many traditional conservatives.

By the 1990s, the communist movement had collapsed as a global secular religion, even though a few relic communist tyrannies survived in China, Vietnam, North Korea and Cuba. The few remaining Marxist radicals in the Western world were mostly English professors hunting for classism and imperialism in the novels of Jane Austen. Nature abhors a vacuum, and as utopianism died out on the left, it found a new home to the right of center. The last generation in the U.S. has seen three forms of demented right-wing utopianism: religious, military and economic.

The religious utopianism was that of the Protestant religious right, which grew in influence in the 1980s and peaked in the 1990s. While the religious right included some Catholics and Jews, its roots were in the Calvinist project of creating a sanctified Christian theocracy on earth. To be sure, most members of the religious right were more moderate than Christian Reconstructionists, who wanted to create an actual Iranian-style theocracy with Christian rather than Muslim content. But the project of remaking a modern, diverse, continental nation on the basis of a book was equally insane, whether the holy book was Marx’s Kapital or the Bible.

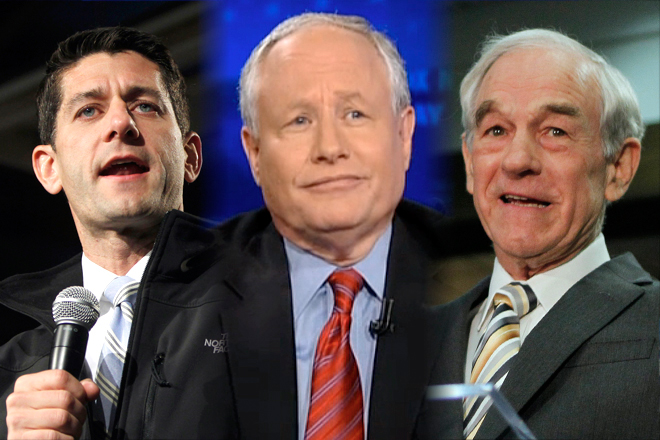

The religious right faded as a force by the early 21st century, largely because of the growing secularization of younger Americans. The next wave of utopianism was military. The older generation of neoconservatives had been New Deal liberals who had grown cautious and skeptical about the ability of public policy to remake American society. In contrast, the younger generation of neoconservatives — some of them literal heirs of the older generation, such as Irving Kristol’s son William Kristol — were wildly optimistic about the ability of the American military to remake foreign societies. Their utopian project of a “new American century” and a “global democratic revolution” exported by force of arms collided with reality in Iraq and Afghanistan in the first decade of the century. When democratic revolutions ultimately did come to the Arab world, they were brought about by citizen revolts, not by American invaders and occupiers.

As the neoconservative utopia faded, it was followed in turn by the libertarian utopia. This time, the utopian social engineering project was not rebuilding America as a theocracy or bombing foreign nations into democracy. This time the utopia was that of the libertarians. Ron Paul went from being a marginal figure to a folk hero for young people in search of gurus, and the works of mid-20th-century prophets of the free market like Ayn Rand and Friedrich von Hayek enjoyed a revival. The libertarian utopia peaked in 2010, around the same time as the Tea Party movement, which helped the Republicans to regain the House of Representatives. To judge by the elections of 2012, in which more Americans cast votes for Democrats for the gerrymandered House as well as in Senate and presidential elections, the public has turned against free market utopians like Paul Ryan, who want to replace social insurance with vouchers and cut taxes further on the rich.

What will succeed the failed utopias of the religious right, the neoconservative right and the libertarian right? For a time, it looked as though the Occupy Wall Street movement might revive a kind of radicalism on the left that has been missing for decades, but after making its useful point about growing inequality, the movement fizzled. Among environmentalists, there have been a few terrorists, like the Unabomber and some eco-vandals, but for the most part, the Green movement is solidly, earnestly middle-class, middle-brow and meliorist.

For my part, I am in no hurry to see any new misguided projects to force reality to fit theory, whether carried out by militants of the left, right or center. I had the privilege of knowing the late Richard Rorty, who followed Irving Howe in distinguishing “movements” from “campaigns” in his book “Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth Century America.” Rorty wrote: “We should not let speculation about a totally changed system … replace step-by-step reform of the system we presently have.”

Single-issue lobbies are a deplorable feature of American politics, but single-goal campaigns have given us everything from the abolition of slavery and segregation to the rights of women and, more recently, of gays and lesbians. Unlike utopian movements, campaigns against specific evils — the sale of assault weapons or the death penalty, for example — are attempts to eliminate specific, limited evils, not efforts to remake society as a whole according to this or that supernatural or secular scripture. A sane society can never have too few utopian movements or too many reformist campaigns.