How literature has no chance whatsoever of saving my life anymore

Kurt Vonnegut: Contemporary writers who leave out technology misrepresent life as badly as Victorian writers misrepresented life by leaving out sex.

“Seattle’s downtown has the smoothness of a microchip,” Charles Mudede says. “All of its defining buildings—the Central Library, Columbia Tower, Union Square towers, its stadiums—are new and evoke the spirit of twenty-first century technology and market utopianism. If there’s any history here, it’s a history of the future. The city’s landmark, the Space Needle, doesn’t point to the past but always to tomorrow.”

Most new technologies appear to undergo three distinct phases. At first, the computer was so big and expensive that only national governments had the resources to build and operate one. Only the Army and a handful of universities had multi-room-sized computers. A little later, large corporations with substantial research budgets, such as IBM, developed computers. The computer made its way into midsized businesses and schools. Not until the late ’70s and early ’80s did the computer shrink enough in size and price to be widely available to individuals. Exactly the same pattern has played out with nylon, access to mass communication, access to high-quality printing, Humvees, GPS, the web, handheld wireless communications, etc., etc. (Over a longer timeline, something quite similar happened with international trade: at first, global interaction was possible only between nations, then between large companies, and only now can a private citizen get anything he wants manufactured by a Chinese factory and FedExed to his shop.)

The individual has now risen to the level of a mini-government or mini-corporation. Via YouTube and Twitter, each of us is our own mini-network. The trajectory of nearly all technology follows this downward and widening path: by the time a regular person is able to create his own TV network, it doesn’t matter anymore that I have or am on a network. The power of the technology cancels itself out via its own ubiquity. Nothing really changes: the individual’s ability to project his message or throw his weight around remains minuscule. In the case of the web, each of us has slightly more access to a mass audience—a few more people slide through the door—but Facebook is finally a crude personal multimedia conglomerate machine, personal nation-state machine, reality-show machine. New gadgets alter social patterns, new media eclipse old ones, but the pyramid never goes away.

Moore’s Law: the number of transistors that can be placed on an integrated circuit—essentially, computational speed—doubles every two years. Most of humanity can continuously download porn (by far the largest revenue generator on the web) ever faster and at ever higher resolution. The next Shakespeare will be a hacker possessing programming gifts and ADD-like velocity, which is more or less how the original Shakespeare emerged—using/stealing the technology of his time (folios, books, other plays, oral history) and filling the Globe with its input. Only now the globe is a billion seats and expanding. New artists, it seems to me, have to learn the mechanics of computing/programming and—possessing a vision unhumbled by technology—use them to disassemble/recreate the web.

I am not that computer programmer. How, then, do I continue to write? And why do I want to?

How literature didn’t save David Foster Wallace’s life

It’s hardly a coincidence that “Shipping Out,” Wallace’s most well-known essay, appeared only a month before Infinite Jest, his most well-known novel, was published. Both are about the same thing (amusing ourselves to death), with different governing données (lethally entertaining movie, lethally pampering leisure cruise). In an interview after the novel came out, Wallace, asked what’s so great about writing, said that we’re existentially alone on the planet—I can’t know what you’re thinking and feeling, and you can’t know what I’m thinking and feeling—so writing, at its best, is a bridge constructed across the abyss of human loneliness. That answer seemed to me at the time, and still seems to me, beautiful, true, and sufficient. A book should be an ax to break the frozen sea within us. He then went on to add that oh, by the way, in fiction there’s all this contrivance of character, dialogue, and plot, but don’t worry: we can get past these devices. In the overwhelming majority of novels, though, including Wallace’s own, I find the game is simply not worth the candle. All the supposed legerdemain takes me away from the writer’s actual project. In their verbal energy, comic timing, emotional power, empathy, and intellectual precision, Wallace’s essays dwarf his stories and novels.

In “Shipping Out,” Wallace phrases himself as a big American baby with insatiable appetites and needs. This may, of course, have been a part, even a large part, of Wallace’s actual personality (I was on a panel with him once and loved how rigorously he scrutinized everything I said, even if I was a little alarmed at the volume of tobacco juice he spat into a coffee can at his feet), but Wallace’s strategy is an example of what Adorno calls immanence: a particular artistic or philosophic relation to society. Immanence, or complicity, allows the writer to be a kind of shock absorber of the culture, to reflect back its “whatness,” refracted through the sensibility of his consciousness. Inevitably, this leads our narrator to sound somewhat abject or debased, given how abject or debased the culture is likely to be at any given point. On the cruise ship the Zenith, which Wallace rechristens the Nadir, he catches himself thinking he can tell which passengers are Jewish. A very young girl beats him badly at chess. He’s a terrible skeet shooter. Mr. Tennis, he gets thumped in Ping-Pong. Walking upstairs, he studies the mirror above so he can check out the ass of a woman walking downstairs. He allows himself to be the sinkhole of bottomless American lack. In order to lash us to his own sickness-induced metaphors, he writes in as demotic an American idiom as possible: “like” as a filler, “w/r/t.” He’s unable to find out the name of the corporation that many of his fellow passengers work for. He keeps forgetting what floor the dance party is on. He can’t figure out what a nautical knot is. He’s unable to tolerate that the ship’s canteen carries Dr. Pepper but not Mr. Pibb.

Drafting off Frank Conroy’s “essaymercial” for the cruise line—“the lapis lazuli dome of the sky”—in much the same way Spalding Gray in Swimming to Cambodia uses the pietistic The Killing Fields and James Agee in Let Us Now Praise continually works against the contours of his original assignment for Forbes, Wallace is nobody’s idea of a reliable reporter: never not epistemologically lost, psychologically needy, humanly flawed. (When a client complained that the roof was leaking, Frank Lloyd Wright replied, “That’s how you know it’s a roof.”) The Nadir promises to satiate insatiable hungers and thereby erase dread by removing passengers’ consciousness that they’re mortal. Ain’t gonna happen: Wallace can hardly say a thing without qualifying it, without quibbling about it, without contradicting it, without wondering if it’s actually wrong, without feeling guilty about it. “Shipping Out” is about Wallace’s flirtation with the consciousness-obliteration plan; the footnotes, finally, are the essence of the essay, making as they do an unassailable case for the redemptive grace of human consciousness itself.

How I once wanted literature to save my life

One of my clearest, happiest memories is of myself at fourteen, sitting up in bed, being handed a large glass of warm buttermilk by my mother because I had a sore throat, and she saying how envious she was that I was reading The Catcher in the Rye for the first time. As have so many other unpopular, oversensitive American teenagers over the last sixty years, I memorized the crucial passages of the novel and carried it around with me wherever I went. The following year, my older sister said that Catcher was good, very good in its own way, but that it was really time to move on now to Nine Stories, so I did. My identification with Seymour in “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” was extreme enough that my mother scheduled a few sessions for me with a psychologist friend of hers, and “For Esmé—with Love and Squalor” remains one of my favorite stories. In college, I judged every potential girlfriend according to how well she measured up to Franny in Franny and Zooey. In graduate school, under the influence of Raise High the Roofbeam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction, I got so comma-, italics-, and parenthesis-happy one semester that my pages bore less resemblance to prose fiction than to a sort of newfangled Morse code.

When I can’t sleep, I get up and pull a book off the shelves. There are no more than thirty writers I can reliably turn to in this situation, and Salinger is still one of them. I’ve read each of his books at least a dozen times. What is it in his work that offers such solace at 3 a.m. of the soul? For me, it’s how his voice, to a different degree and in a different way in every book, talks back to itself, how it listens to itself talking, comments upon what it hears, and keeps talking. This self-awareness, this self-reflexivity, is the pleasure and burden of being conscious, and the gift of his work—what makes me less lonely and makes life more livable—lies in its revelation that this isn’t a deformation in how I think; this is how human beings think.

How an awful lot of “literature” is to me the very antithesis of life

We live in a culture that is completely mediated and artificial, rendering us (me, anyway; you, too?) exceedingly distracted, bored, and numb. Straightforward fiction functions only as more Bubble Wrap, nostalgia, retreat. Why is the traditional novel c. 2013 no longer germane (and the postmodern novel shroud upon shroud)? Most novels’ glacial pace isn’t remotely congruent with the speed of our lives and our consciousness of these lives. Most novels’ explorations of human behavior still owe far more to Freudian psychology than they do to cognitive science and DNA. Most novels treat setting as if where people now live matters as much to us as it did to Balzac. Most novels frame their key moments as a series of filmable moments straight out of Hitchcock. And above all, the tidy coherence of most novels— highly praised ones in particular—implies a belief in an orchestrating deity or at least a purposeful meaning to existence that the author is unlikely to possess, and belies the chaos and entropy that surround and inhabit and overwhelm us. I want work that, possessing as thin a membrane as possible between life and art, foregrounds the question of how the writer solves being alive. Samuel Johnson: A book should either allow us to escape existence or teach us how to endure it. Acutely aware of our mortal condition, I find books that simply allow us to escape existence a staggering waste of time (literature matters so much to me I can hardly stand it).

How I once wanted language to save my life

A student in my class, feeling self-conscious about being much older than the other students, told me he’d been in prison. I asked him what crime he’d committed, and he said, “Shot a dude.” He wrote a series of very good but very stoic stories about prison life, and when I asked him why the stories were so tight-lipped, he explained to me the jailhouse concept of “doing your own time,” which means that when you’re a prisoner you’re not supposed to burden the other prisoners by complaining about your incarceration or regretting what you’d done or, especially, claiming you hadn’t done it. Do your own time: it’s a seductive slogan. I find that I quote it to myself occasionally, but really I don’t subscribe to the sentiment. I’m not, after all, in prison. Stoicism is of no use to me whatsoever. What I’m a big believer in is talking about everything until you’re blue in the face.

How literature might just still save my life

I no longer believe in Great Man Speaks.

I no longer believe in Great Man Alone in a Room, Writing a Masterpiece.

I believe in art as pathology lab, landfill, recycling station, death sentence, aborted suicide note, lunge at redemption.

Your art is most alive and dangerous when you use it against yourself. That’s why I pick at my scabs.

When I told my friend Michael the title of this book, he said, “Literature never saved anybody’s life.” It has saved mine—just barely, I think.

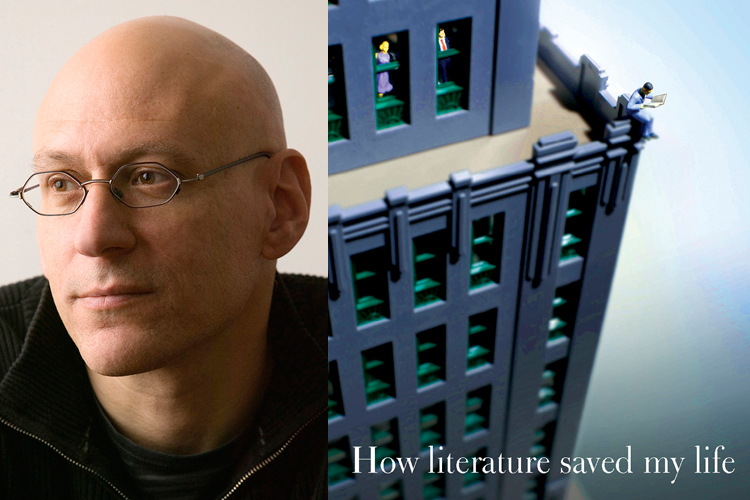

Excerpted from HOW LITERATURE SAVED MY LIFE by David Shields. Copyright © 2013 by David Shields. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.