Although he traced and painted and wrote in obscurity until the day he died, Henry Darger is, today, probably the best-known outsider artist in the world. In the past decade or so, the confines of his one-room Chicago apartment have ceded to the spacious galleries of museums and art fairs, and Henry Darger — a man who kept mostly to himself, not quite reclusive but not incredibly social either — has become the poster child of outsider art.

But what happens when someone becomes famous, especially posthumously, is you (or I) sometimes forget that there is or was a person behind that fame — a real person, a human being, who lived a life and created the art that people now refer to, both succinctly and dismissively, as “those paintings of the little girls with the penises.” It’s good to remember and revisit that human being once in a while.

A week and a half ago, thanks to EFA Project Space and its current exhibition on artists’ novels,The Book Lovers, I had the amazing opportunity to do just that with Darger. In conjunction with the show, the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM) had agreed to host a very small visit to its archives to take in some of its Darger material (the museum has the largest collection of his work in the world). Although I had seen the documentary about Darger, In the Realms of the Unreal, with my family on Christmas Eve eight years ago, I didn’t remember the particulars of his biography very well. I wasn’t quite sure why an exhibition about artists’ novels afforded a trip to the Darger archives (though I obviously wasn’t complaining).

Darger’s writings (image via American Folk Art Museum)

Darger’s writings (image via American Folk Art Museum)

Once the 10 or so members of our group had arrived and signed in, Kevin Miller, a warm and incredibly smart former Darger fellow at AFAM, led us past file cabinets and bubble wrap and freestanding sculptures to an area where a few pieces had been laid out on tables for us to see. It was then that the reason, or at least the pretext, for our trip became clear: two huge volumes, both with spines probably six inches thick, sat in open boxes on a table, their covers painstakingly assembled from cardboard and wallpaper. These were two of the seven books that comprise Darger’s 15,000-page (give or take) novel, The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion.

When I say novel, I mean it in the old-fashioned sense — not graphic novel or illustrated novel or picture book. The mesmerizing paintings for which Darger’s become famous tell a similar, perhaps the same story (no one’s read the whole novel, so it’s not clear), but the book itself consists of page after page, volume after volume of tight, condensed, single-spaced blue type.

Oh yes, and Darger wrote the novel by hand first, beginning probably in 1909. Then he typed it.

Ann-Marie Reilly, the American Folk Art Museum’s chief registrar and director of exhibition production, talking to the group; one of Darger’s volumes can be seen in the foreground.

Ann-Marie Reilly, the American Folk Art Museum’s chief registrar and director of exhibition production, talking to the group; one of Darger’s volumes can be seen in the foreground.

As Miller explained it, The Realms of the Unreal is a war story, an epic tale influenced by the adventure stories and serials and comic books of its time. It begins with a first-person narrator speaking from the trenches but quickly spins out into the fantastical story of the Vivian Girls (those little girls drawn with penises) and their battles with the Glandelinians, evil adults who practice child slavery. Miller said that although he hadn’t read all of it — and, as he quipped, “anybody that wrote a 15,000-page novel probably needs a good editor” — he could attest to parts of it being quite good: moving, self-reflective, funny. A third volume was laid out open on another table, and I leaned over to read some of it. I managed to transcribe this snippet:

The rooms and wars, were crowded thick with sufferers, too many to be counted, broken and shattered in every conceivable way by wars [sic] machinery of death.

That line stuck with me, probably because it’s good. Melodramatic, yes, but well-written, too — even a bit Dickensian (A Tale of Two Cities was among the books found in Darger’s room after he died), and it evokes an intense image of the brutality of war. Darger was drafted in 1917, but after training for a few months, he received an honorable discharge. Still, he lived at a time when the world was bloody (when hasn’t it been?), and clearly he felt it acutely.

It turns out the novel wasn’t the only thing Darger wrote. There’s also a second novel, called Crazy House; an autobiography that apparently contains only a small amount of autobiographical information before turning — on a simple phrase along the lines of, “Oh yeah, there’s one thing I forgot to mention … ” says Miller — into another fantastical story; and, my favorite, a series of weather journals, in which Darger wrote on one side the predicted weather forecast for a given day, and on the other, what the weather actually was. (The Awl’s unrecognized precedent?) One of these is on view in Compass, the AFAM exhibition currently at the South Street Seaport Museum.

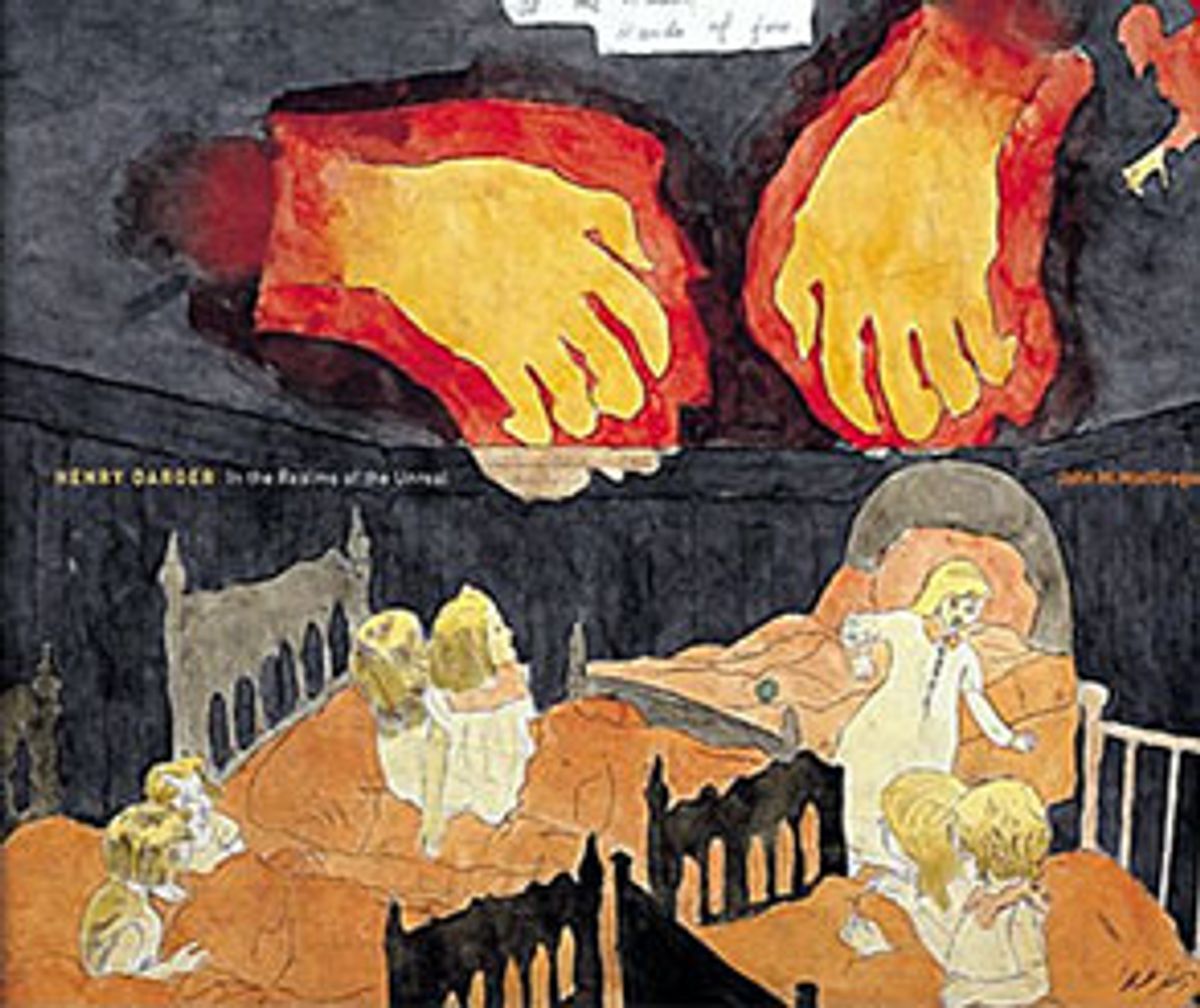

Henry Darger, “18 At Norma Catherine. But wild thunderstorm with cyclone like wind saves them.” (mid-20th century), watercolor, pencil, colored pencil, and carbon tracing on pieced paper, double-sided, 19 1/8 x 47 3/4 in. (image via American Folk Art Museum)

Henry Darger, “18 At Norma Catherine. But wild thunderstorm with cyclone like wind saves them.” (mid-20th century), watercolor, pencil, colored pencil, and carbon tracing on pieced paper, double-sided, 19 1/8 x 47 3/4 in. (image via American Folk Art Museum)

Despite his having written an ostensible autobiography, Darger didn’t leave behind much information about himself, either through first- or secondhand sources. Researchers don’t fully understand what the connection was or is meant to be between Darger’s writings and his visual art. He refers to himself in the autobiography as an artist, but he also mentions, at some point inThe Realms of the Unreal, the possibility of publishing the novel and becoming rich and famous.

In the end, perhaps a bit ironically, it was the art that made him famous. But seeing the volumes of the novel laid out, their pages worn and delicate but jammed with unrelenting type, reminded me of what drives art — not just outsider, but all of it — the reason why some people make it and others of us look on in awe: that need for human communication, the urge to tell a story and be heard.

The Book Lovers continues at EFA Project Space (323 West 39th Street, 2nd floor, Midtown West, Manhattan) through March 9. Compass is on view at the South Street Seaport Museum (12 Fulton Street, Financial District, Manhattan) through March 31.

Shares