They’d greeted each other a few times in passing, but the semi-friendship between Whitey Bulger and Josh Bond began in earnest during the summer of 2007 after Josh moved into unit 304 of the Princess Eugenia Apartments. Late one afternoon, Josh was walking around his apartment hugging his guitar while strumming a mix of blues and country. He and a musician friend named Neal Marsh were teamed up and starting a band, For the Kings, with hopes of playing in Los Angeles-area clubs and eventually recording an album.

Some of Josh’s songs were original; others were by Elvis Presley, Hank Williams, the Rolling Stones, and the Band. He played hard and sang loudly, and he knew the old couple in the next apartment could probably hear him, but this was his time to practice and to recover from work. He usually came home from the manager’s office, located in the hotel across the street, wiped out from talking with tenants, suppliers, staff, and guests and servicing their varied needs.

He finished playing, collapsed onto the couch in the living room, and zoned out. Then he heard a knock at the door. Josh didn’t move. No one had ever knocked on his door since he’d moved in. He’d purposely avoided being neighborly with the tenants; he didn’t want them thinking that just because the general manager lived in the building he was available around the clock.

Josh yelled, “Who is it?” “Charlie.”

“Who?”

“Your neighbor.”

Josh reluctantly pulled his lanky frame up and sauntered across the room. He opened the door but only a crack. Standing in the hallway was the white-bearded man from next door. Josh, in his role as general manager, of course knew his name: Charlie Gasko. The man was holding a big, black hard plastic can. Josh had no idea what was in the container, and his first thought was it might be a tambourine case, and his second thought was the old guy maybe wanted to play music.

But Josh, scruffy-bearded, just stood there; he didn’t open the door or invite the man in. The man, however, smiled and said he’d been listening to Josh’s music and thought Josh was pretty good. “I thought you should have this.”

Whitey handed the container to him. Josh opened it up. Inside was a cowboy hat. Josh lifted it out: the hat was a black wool Stetson Stallion with a leather band studded with engraved silver buttons. The man went on to say that it was an old hat of his, that he didn’t need it anymore and thought Josh might have use for it.

“Oh,” Josh said. He was thinking, This was weird, but said, “Cool. Thanks.”

Josh took the hat and closed the door.

*

But Whitey wouldn’t go away. He returned another afternoon, and then another, knocking on the door and looking to “shoot the shit” with “Tex”—a nickname Whitey initially gave Josh but that wore out its welcome quickly.

“If he knew I was here he’d knock on the door,” Josh said.

Josh didn’t want to be rude, so he let Whitey in a first time, then a second time, until Whitey was coming by to talk a couple of times a week. That was the pattern that developed—Whitey talked and Josh listened. Josh, it turned out, was a good listener. Though from Mississippi, he did not possess one of those outsized, good-old-boy southern personalities—because if he had, the odd coupling of Whitey and Josh likely would not have worked out. Whitey wasn’t really looking for someone who could match his story with one of his own. He wasn’t looking for a real conversation. He wanted a sounding board.

Josh, then, was yin to Whitey’s yang—with a natural reserve that was actually refined as a result of working in the service industry. Josh’s job required a helpful, friendly demeanor as he dealt with people all day long, but as a matter of survival he self-consciously developed the ability to smile and project the appearance of being attentive when in fact he was zoning out. Plus, he’d learned to say little and ask few questions, because that would simply extend conversations. This served Whitey perfectly—talking to someone bright and youthful but without the kind of inquiring mind that might create problems. He’d arrive home in the afternoon—his lunch break when working the hotel desk—and then would come the knock, and in would come Whitey. “He would start talking,” Josh said. “Talk about anything.” Talk until Josh stood up. “Okay, I got to go back to work.”

Much went in one ear and out the other, but over time enough stayed with Josh that he acquired a superficial mix of Whitey personal fiction and commentary. Whitey said he was from Chicago, that he and his wife had no kids and they’d retired to Santa Monica in the 1990s. He told Josh he’d seen action in Korea. He mentioned his high blood pressure and that he sometimes traveled to Mexico to buy heart medication. There were the swipes at President Obama and opinions on local crime and public safety. Whitey sometimes circled an article about a neighborhood crime or about city legal news regarding hotels and left the newspaper outside Josh’s door with the idea that, as general manager, the stories were relevant to him.

Josh occasionally partied with friends in his apartment—and he sometimes took the party up onto the roof of the building, under Santa Monica’s starry night sky. The next time Whitey knocked on the door Josh braced for a complaint, but none came. Instead Josh listened to a bemused Whitey note that Josh hosted gatherings sans swearing, macho preening, and fistfights—party conduct apparently foreign to Whitey.

Josh rarely went inside Whitey’s apartment, and one such time was when Whitey wanted to show him a new pair of headphones to use while watching television late into the night without waking up Carol [the name used by Whitey’s girlfriend, Cathy Greig]. Josh saw the futon bed in the living room and, except for the punching dummy, nothing seemed peculiar for a retired couple who at this point in their lives slept in separate bedrooms. Josh could tell Whitey liked his company and sometimes the sessions in the apartment weren’t enough; if Josh was entering the building and ran into his neighbors, Whitey wanted to talk. But Cathy would say, “C’mon, Charlie. Leave Josh alone. He’s got places to go.”

Whitey had two recurring topics: music and personal hygiene. Whitey liked to critique Josh’s music, opine on which songs he liked, inquire about where Josh was playing, and offer business advice. He also talked endlessly about personal maintenance and fitness. The unsolicited advice covered the gamut. Whitey observed that the bicycle Josh rode around a lot did not have a headlight. He said Josh could do a better job taking care of his scruffy beard and that he could strengthen his arms immeasurably if he used a certain piece of equipment.

Then came the gifts. The Stetson hat was the first. Then Whitey gave Josh a beard trimmer and comb, and used his own white beard as a model in urging tidier upkeep. He gave Josh a curling bar, free weights, and a stomach crunching device. Josh thought the gifts were over-the-top, even strange. When he realized many were directed at his appearance, he had a crazy notion that maybe the old guy was coming on to him. But Whitey never gave off a vibe along those lines, and they “were such a nice old couple” that Josh dismissed the thought. He decided Whitey was simply treating him like the son he didn’t have.

Whitey and Cathy gave him gifts at Christmas, too—a decorative plate one year, an Elvis coffee table book another. Josh also learned Whitey was obsessed with mannerly protocol. One year Whitey had left a Christmas gift bag on Josh’s door, and a few days later Josh ran into Whitey in the building’s underground garage.

“You get the present?” Whitey asked.

Josh could tell Whitey was perturbed. “Oh, yeah. Thanks, Charlie.” “Don’t you write thank-you notes?”

Josh fumbled for words. When he got home he tore out a sheet of lined notebook paper and wrote a note to Charlie and Carol thanking them for the gift and for being such terrific next-door neighbors. The next time Whitey came by he was smiling and bearing more gifts—a box of stationery and bread Cathy had baked. “Carol loved the note,” Whitey said. “You’re all set now; no need to write anymore.”

*

Overall, Josh Bond probably got a deeper glimpse than anyone else in Santa Monica, past the eyes of Charlie Gasko and toward the heart of darkness that was Whitey Bulger. One episode involved a resident from the Ocean View Manor, the state-licensed residential facility for the mentally disabled located a few doors down from the Princess Eugenia Apartments. The manor was home to forty-four mentally disabled adults, many of whom had lived there for years, participating in programs encouraging them “to become more independent and self- sufficient in order to eventually return to the community and into society.” Josh was familiar with the manor because on occasion a resident moseyed into the lobby of the Embassy Hotel and “caused a bit of trouble.” Nothing huge, but incidents Josh certainly had to manage. It turned out Whitey had his own close encounter. One resident was known to hide behind a bush along Third Street and then jump out to spook a passerby. The resident just thought he was being funny, but Whitey didn’t see the humor, and he told Josh that he and Cathy were on their late-day walk when the resident popped out from behind a bush. Cathy was frightened, Whitey said, and this had set him off. He kept a knife strapped to his ankle and said he’d grabbed the guy, pulled out the knife, and held the man’s face close to him. “I told the guy if I ever see you do that again I’m gonna cut you.”

Josh soon experienced for himself that Whitey did not like surprises. One day after work he’d changed into his running clothes, grabbed his iPod, and hustled onto the elevator to head out for a jog. In the lobby he spotted Whitey standing on the building’s front stoop, his back to the lobby, hands resting on the iron railing, just looking up and down the street. Josh had already noticed that Whitey, when standing, “had this look,” where his feet were planted, his arms were arched out a bit and, if not holding a railing, then arched as if he was going to rest them on his hips. It was hard for Josh to put the look into words — maybe the look of a gunfighter ready to draw his gun. Or maybe a look rooted in a past Josh knew nothing about—Whitey’s body muscle memory from his days as crime boss, when he posed in the open bay at the Lancaster Garage or at some other venue projecting near-absolute power while surveying his territorial holdings. Sometimes when Josh saw Whitey posturing this way Whitey might smile and glare, and that’s when Josh would notice Whitey’s very white teeth and bright blue eyes, and Whitey might also chortle, where his upper body and arms shook along with the sound. “It was a weird laugh,” Josh said, “a laugh with almost some anger behind it.”

Whitey was ahead of him on the stoop and Josh, coming up quickly behind him, said, “Hey, Charlie, what’s up?” But because he was wearing headphones it came out more like yelling, “HEY, CHARLIE, WHAT’S UP?” Whitey’s hands flew up off the railing. Josh saw Whitey jump, turn, and look hard at him. Then Whitey began shouting, his mouth like an automatic weapon getting off a few rounds.

“Goddammit! Fuck! Fuck! Jesus Christ. Fuck!”

Josh was dumbstruck by the hyper-angry string of curses—something he’d never seen in Charlie Gasko, a break in character from the friendly guy next door who insisted on thank-you notes and marveled at parties where guests did not swear.

But maybe Whitey had thought he’d been ambushed—surrounded by the FBI? A Mafia hit man? Johnny Martorano? Hadn’t Martorano on “60 Minutes” said, “There’s a bounty on him”?

Then Whitey saw it was only Josh Bond, and he calmed down quickly.

“Jesus, Josh, don’t sneak up on me like that,” he said.

*

By the summer of 2010 a new dawn had finally come to Boston law enforcement and the Bulger Task Force. Three key federal offices in Boston now had new leaders. Carmen Ortiz was confirmed as the new U.S. attorney in Massachusetts in November 2009; John Gibbons, who’d served twenty-seven years with the Massachusetts State Police, was sworn in as U.S. marshal for the District of Massachusetts in February 2010; and Richard DesLauriers, a Massachusetts native who’d previously served in Boston, officially took over as the FBI’s special agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office on July 1, 2010. Representatives from the three offices began meeting to discuss the hapless Bulger Task Force and the interagency logjam that had undermined a unified front in the hunt for America’s most wanted, Whitey Bulger.

Federal marshals had been hungering for years to get involved—a new generation of proactive deputy marshals who combined street savvy with sophisticated electronic surveillance to track fugitives. “We were licking our chops,” said a deputy marshal and supervisor named Jeffrey Bohn, who’d cut his teeth in Miami and had been in Boston about a decade. Many marshals viewed the FBI of the twenty-first century as institutionally hampered by two key factors—first, the bureau’s phasing out of its fugitive operations, particularly after 9/11, resulting in eroding expertise, and second, its approach—seen as reactive, with FBI agents inclined to sit at desks studying computer screens rather than pounding the streets. Dating back at least a year, marshals in Boston had even put together a memorandum outlining a new task force—its manpower and strategy—that they wanted to put in play if given the chance. The marshals exuded confidence, saying Whitey would have been apprehended long ago if they had been unleashed from the start in 1995.

But the proposal required the one condition that had always stopped such ideas dead in their tracks: in the official jargon, the plan called for the FBI to “delegate apprehension” to the marshals service. In other words, the FBI would have to step aside. During meetings that spring, the FBI representatives made it clear they wanted help—that the FBI needed the marshals’ expertise—but reiterated their position that the FBI had to be the lead agency, given its scandalous past ties to Whitey.

Marshal John Gibbons; his chief deputy, Dave Taylor; his assistant deputy chief, John Murray; Boston FBI assistant special agent in charge, Noreen Gleason; and representatives from the U.S. attorney’s office—all wanted to get past the deeply rooted mistrust. It was 2010—meaning there were FBI agents, deputy marshals, state troopers, and federal drug agents now working in the field who hadn’t been born or had been toddlers when Whitey Bulger was at the pinnacle of power in the 1980s, guarded by a corrupted FBI.

So Gibbons decided, why not? Headquarters in Washington might be against any plan that did not call for marshals to be in charge, but Gibbons had the latitude to allocate his manpower. He wanted to set a different tone, try for a new vibe. The FBI in Boston had asked for the marshals’ help, and Gibbons and his deputies decided it was time. They would assign a marshal to the cause.

Gibbons chose a deputy marshal named Neil Sullivan. Sullivan had grown up on Cape Cod and became a marshal in October 1995. He had been working in Albany, New York, on the “warrant squad”—meaning fugitive cases—and supervising a fugitive task force when he transferred to Boston in 2009. “We knew his reputation before he came to Boston as an outstanding investigator,” Gibbons’s chief deputy Taylor said. Just as important, Sullivan was “non-abrasive” and was known as a team player.

For the FBI’s part, it was assigning an agent named Phil Torsney to work with Sullivan. Torsney was a throwback; he’d worked on fugitive cases for the FBI for more than two decades, most recently assigned to the bureau’s office in Cleveland. With a career passion for working fugitive cases, some marshals considered him an FBI dinosaur, given the modern bureau’s focus on counterterrorism. Over the years Torsney had been loaned for short periods to the Bulger Task Force from Cleveland, but he was now being transferred to Boston so that he could finish his FBI career working on Whitey. Torsney was known for his upbeat, can-do approach—exactly the attitude necessary for the Whitey manhunt. The task force’s coordinator, FBI agent Richard Teahan, would stay in that role although continuing to split his duties with another unit. Jon Mitchell, the federal prosecutor assigned to the task force, also would continue to divide his time between the task force and other matters.

Sullivan was soon briefed on his new assignment and told he was joining a beefed-up, reconstituted Bulger Task Force. Following the necessary paperwork, he showed up for work September 2010. When he arrived at the task force’s nondescript office in One Center Plaza in Boston he was slightly taken aback. The walls were covered with dozens of photographs—of Whitey and Cathy, of their many relatives, of Whitey’s many associates—as well as with charts and world maps with pins stuck in various locations. Desks with computers lined the large room. But it was as if someone had yelled “Fire!” The office was empty and dead quiet, hardly the high-octane manhunt as advertised.

In reality it was going to be a task force of three—Sullivan, Torsney, and an FBI analyst named Roberta Hastings. Two investigators and an analyst. Not much in the scheme of all the resources at the disposal of the giant federal agencies. But in the context of a Bulger manhunt that was barely on life support, this was a fresh start.

During the fall Sullivan and Torsney got up to speed. The two investigators studied past strategies, assessed past alleged sightings, reinterviewed persons previous task force members had thought might have insights about Whitey’s whereabouts—some who would talk only to Sullivan because they mistrusted the FBI and were convinced the bureau was protecting Whitey. They each arrived at similar positions about the state of Whitey Bulger affairs—that Whitey was alive, not dead; that the much-ballyhooed London sighting of 2002 was bogus and had steered searchers off track; that Whitey and Cathy Greig were hiding in the States; and that he and Cathy were living near the water and in a warm-weather climate.

They learned that during the previous year an effort had begun to employ new facial recognition technologies to search databases of driver’s licenses. The idea was to see whether Whitey’s or Cathy’s face popped up on a license in the name of an alias. There was no federal database of licenses, however, which meant the process was slow and time-consuming, involving going to each state’s motor vehicle registry. That initiative continued into 2011, with about half the states accounted for—California being one of the states not yet covered.

And they began brainstorming new ideas with task force prosecutor Jon Mitchell and others in a bid to revitalize the manhunt. The idea was to put the spotlight on Cathy Greig, using new photographs that the task force had obtained. The photos were of Cathy before she fled with Whitey, but they were fresh, enhanced images the public had not yet seen. The task force started small with this new Greig-based publicity campaign, taking out advertisements in two trade journals, Plastic Surgery News and the American Dental Association monthly newsletter, in the spring of 2010.

“The thinking was anyone who had plastic surgery in her thirties would have more, not less, as time goes on,” Mitchell said, “and anyone as fastidious about her teeth would stay that way.”

But, as with every other publicity campaign to catch Whitey, nothing came of the trade journal ads. Even so, as Sullivan and Torsney teamed up during the fall of 2010 they liked this idea-in-progress—of paying more attention to the woman in Whitey’s life. It hadn’t really been tried before, and it made common sense. Cathy was attractive and more social, and anyone encountering the couple might well remember her better than the bearded man with glasses and hat pulled down.

*

The next spring, on May 1, 2011, U.S. Navy SEALs descended stealthily into a private compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, where they shot and killed Osama bin Laden. The raid brought an end to the leader of al-Qaeda, who had been the mastermind behind the September 11, 2001, attacks in the United States.

And it dislodged bin Laden as the most notorious entry on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list, making room at the top for the legendary Boston fugitive Whitey Bulger.

In Santa Monica, in the wake of the news about bin Laden, Whitey Bulger cum Charlie Gasko hunkered down in Unit 303, becoming even more reclusive.

Whitey posted a note on his apartment door, hand-printed in thin block letters: “PLEASE. Do Not Knock On This Door At This Time. Thank You.” Cathy Greig began telling other tenants her husband’s Alzheimer’s disease was worsening.

Whitey once had had a talk with Cathy about options if he should die—she could either go home to Boston or stay on as Carol Gasko in Santa Monica, living off the cash he’d stashed in the walls.

But Whitey was of sharp mind and good health in May 2011—and as he withdrew further into his tiny world at the Princess Eugenia the reason had nothing to do with failing health. He might be eighty-one but he was nowhere near death’s door. Instead, it was as if Whitey sensed a change in the wind, a possible storm brewing.

And staying by his side was Cathy Greig, who’d made her choice long ago.

*

The same month that bin Laden was killed, the Bulger Task Force in Boston applied the finishing touches for a June launch of its latest publicity campaign targeting the fugitive couple. Neil Sullivan, Phil Torsney, supervisor Teahan, and prosecutor Mitchell were taking the next step in the Greig-angled strategy—going big, a campaign plastering Greig’s face before the general public and, in particular, the mostly female audience watching soap operas and other daytime television shows. The heart of the campaign was a thirty-second spot with photographs of Cathy and Whitey along with information about the international manhunt to run during commercial breaks. Cathy’s reward was being doubled to $100,000 while Whitey’s was still $2 million, tops on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list.

They bought time on stations in fourteen cities—but skipped Los Angeles and New York City, in part because the TV ad rates in those markets were budget busters for the campaign’s fifty-thousand-dollar fund. Ads were scheduled to run during such shows as Live with Regis and Kelly, Ellen, and The View. To maximize the publicity push, they also arranged to feature Whitey and Cathy on digital billboards in about forty states as part of the FBI’s fugitive billboard program, where billboard owners donated space to the FBI. Finally, a press release was drafted explaining the new initiative in hopes that the media would run news stories about Whitey and Cathy.

Neil Sullivan and Phil Torsney got ready for the start of the new publicity campaign on June 20. Sullivan planned to oversee the morning/afternoon shift while Torsney would cover the afternoon/evening shift. Extra analysts were deployed to their office to handle the surge in telephone calls.

The whole idea behind this and any other publicity campaign was simple—to get lucky. To reach that one person who, seeing the ads or spin-off news media coverage, recognized Cathy or Whitey or both—a person who’d been in the right place at the right time to cross paths with the fugitive couple. That was what the manhunt for years had been all about—luck—and, after so many luckless years, the karma this time was going to be different.

*

On a Friday two weeks before the new campaign was scheduled to start, Cathy Greig, out doing errands, stopped at the local pharmacy to pick up a refill of Whitey’s heart medication. She signed for the prescription using Whitey’s main alias, James W. Lawlor. Her entering and leaving the store were captured on the store’s security camera.

On a later June weekday Cathy walked into the Haircutters on Wilshire Boulevard—her last haircut, it turned out, before the start of the media blitz. Hairdresser Wendy Farnetti was glad to see her. Cathy had missed a previous appointment. “She sort of disappeared, and I was worried,” Wendy said. “I thought, where did she go?”

Cathy settled into a chair. “Her hair was a mess,” Wendy said. “It was long.” Cathy wanted the usual—cut short on the top and sides, shaggier in back. The hairdresser noticed she seemed “really distraught, really nervous.”

Wendy asked, “What’s wrong?”

“You don’t know,” Cathy said. “You don’t even know.”

Wendy Farnetti wasn’t alone noticing something different. Josh Bond didn’t make much of it but one day he realized the knocks at his apartment door had stopped. He might see Carol Gasko heading out to do an errand, but it had been more than a month since Charlie Gasko had stopped by.

“Probably the longest I went without seeing him,” he said.

*

The launch of the new Whitey and Cathy media blitz on Monday, June 20, 2011, went smoothly. FBI officials and federal prosecutors held a press conference in Boston to unveil the latest publicity campaign. The thirty-second commercials began appearing on daytime television in fourteen cities, and the news media, especially cable networks CNN and Headline News, gave the new Cathy Greig angle plenty of coverage that aired around the globe.

The two most interested viewers in the world caught the news while watching TV inside their rent-controlled apartment at the Princess Eugenia in Santa Monica, California. The end of bin Laden, and now the new focus on Cathy—Whitey had always wondered why they hadn’t focused on Cathy; she was the more social of the two, circulating in the world while he was largely a shut-in. She was more memorable.

Whitey later said he had a hunch and turned to Cathy, saying, “This is it,” although investigators doubted the claim of clairvoyance. They saw the claim as another example of “Whitey ragtime”—his need to seem all-knowing. If Whitey had truly had a hunch he should have cleared out for a few weeks, just in case.

The next day, Tuesday, Deputy U.S. Marshal Neil Sullivan and FBI agent Phil Torsney thought they had something. Seven or more tips reporting possible Whitey sightings came in from Biloxi, Mississippi, and the surrounding area. The team began to get pumped up—a cluster of calls was the kind of thing you looked for, plus the Deep South was historically a location Whitey was known to inhabit—Grand Isle, Louisiana, being the most notable. But as quickly as the barometer of excitement had risen, it had fallen. By day’s end none of the tips had checked out—the information too vague, inconsistent, unverifiable. Sullivan and his colleagues concluded that the handful of calls from the same geographic area had been an odd coincidence.

Under rainy skies Wednesday morning Sullivan arrived to work at the task force office in Boston around six o’clock, wondering what this day, the third of the new Whitey media blitz, would bring. During the first forty-eight hours they had received more than two hundred calls, and Sullivan saw that some of the extra analysts brought on board were already going through voice mails left on the task force’s toll-free 800 number during the early-morning hours when the office was not staffed.

Sullivan ordinarily would listen to the voice mails, too, but instead began going through the stack of tip sheets. The phones were continuing to ring, with analysts busy writing down information from new tipsters who thought they had a bead on the whereabouts of Whitey Bulger and Cathy Greig. Sullivan reviewed the tip sheets when one caught his eye—a sheet summarizing a predawn voice mail left by a woman, a woman with an accent who said she was calling from Europe to report that Cathy Greig and Whitey Bulger were living in Santa Monica, California.

The caller had even provided an address—an apartment on Third Street. That was the detail that grabbed Sullivan’s attention. Most common were tips along the lines of Whitey was spotted in such-and-such a town at a convenience store at such-and-such a time—fleeting information that wasn’t really helpful in that there was no meat, nothing that could really be followed up on. But a detail like this—a specific address—was exactly what a deputy marshal was trained to spot in a pile of tip sheets, most of which signified nothing. Sullivan continued working his way through the other sheets but he put this one aside.

Then, shortly after 9 a.m., the task force got a call from the FBI office in Los Angeles, referring a tip it had received the previous night about a possible Whitey sighting in Santa Monica. Sullivan right away saw that the tip was from the same woman from Europe who’d called Boston and left a message. Then around 11 a.m. an analyst handed Sullivan the sheet from a tipster he’d just finished talking to on the phone. Sullivan saw why—it was the woman again, reporting that she was calling from Europe and had seen the news on CNN about the media blitz and that she was certain Whitey and Cathy were in Santa Monica posing as the couple Charlie and Carol Gasko.

Sullivan quizzed the analyst. How did the woman sound? Sane? Believable? Crazy? The analyst told him she sounded solid. The tip was radiating heat—the specifics combined with the caller’s persistence—leaving a message in Boston, calling Los Angeles, then calling Boston back. Sullivan put everything else aside, took the tip sheet, and tried calling the woman on the telephone number listed on it. He had in hand a lead gaining traction, and his intensity was building. But something was wrong. The call went nowhere—no voice mail, just noise and static. He tried using a different landline in the office, thinking maybe something was wrong with the first phone he’d used. The call still didn’t go anywhere. He tried his cell phone—still nothing.

Thirty minutes later—about noon on Wednesday in Boston—his cell phone rang. The caller was Anna Bjornsdottir, and for the next twenty minutes Sullivan talked with the woman who’d been calling Boston and Los Angeles about the manhunt for Whitey Bulger and Cathy Greig.

Sullivan could tell from the start she had it all—their height, weight, and mannerisms. She gave a specific address at the Princess Eugenia Apartments in Unit 303, and she mentioned the couple’s heavy accents, which they’d told her were New York accents. She talked about the couple’s daily walks, their affection for dogs and cats. She described a particular stray cat named Tiger and explained the friendship that had developed with Cathy because of Cathy’s care for the animal. She included that Cathy was nice while Whitey, ever present during their encounters, could be nasty, and she described the hard feelings following a discussion of President Obama. The woman was 100 percent certain about the Gaskos’ true identity.

Sullivan knew she was right, too, and the deputy U.S. marshal was now in full operational mode. He told her they were going to move on the lead as quickly as possible and then, as was standard operating procedure, he issued a series of warnings—that she was not to discuss the manhunt with anyone, not her husband, a friend, a relative, no one; that a dangerous fugitive, a killer, was at stake, as well as a two-million-dollar reward. She promised to cooperate and await further instructions.

Once the call ended, Sullivan got on to the computer to run some quick background checks on Charlie Gasko—looking for a Social Security number, a date of birth, a credit history, anything that would indicate an official existence. He confirmed that a Charles Gasko lived at the same Third Street address the woman tipster had provided, but nothing else showed up. Not even a date of birth, and without a date of birth he could not continue to search for any state licensing information, such as a California driver’s license, a car registration, even parking tickets. In Boston he did not have access to the California database that allowed searches using only a person’s name. He turned to an FBI staffer to call an FBI bureau in California to quickly run a motor vehicle and license check on both Charles and Carol Gasko. Once again nothing turned up. This, Sullivan knew, was not typical, a red flag indicating the persons in question were trying to go undetected.

It was early afternoon now in Boston. Sullivan’s instinct was to contact his fellow marshals in Los Angeles to deploy a team to capture their man, but this was the FBI’s task force. He notified the task force’s supervisor, FBI agent Richard Teahan, about Anna and the background search, saying, “This tip needs immediate coverage.” Teahan listened and tried to contact the FBI office in Los Angeles but left a message when the agent he called did not pick up. Sullivan watched this unexpected pause and grew antsy—everything about the tip screamed this was Whitey Bulger. Sixteen years after he fled Boston. Sixteen years on the run.

Twenty minutes went by, and Sullivan went back to Richard Teahan, diplomatically mentioning that time was of the essence and urging him to call Los Angeles again. “We can’t wait,” he said. Teahan, agreeing with Sullivan’s sense of urgency, called the Los Angeles bureau a second time, this time getting through to another agent, an agent named Scott F. Garriola. Garriola did not work on a fugitive squad—he was a member of the Violent Crimes Task Force—but the minute Sullivan began working with him he could tell Garriola got it. Sullivan briefed Garriola and brought him up to speed about the Gasko tip from Anna Bjornsdottir and the apartment location in Santa Monica. Then Sullivan played the middleman, sending a text message to Anna and arranging for her to talk to an FBI agent in Los Angeles. The direct connection made, Sullivan stepped aside so that Garriola and Anna spoke directly. By this time it was about mid-afternoon in Boston, midday in Los Angeles. FBI agent Scott Garriola, after his own conversation with the tipster, informed Boston he would immediately “get eyes” on the apartment—and that he would take it from there.

*

Josh Bond had been working extra-long hours for more than a week while the other manager, Birgitta Farinelli, was away on vacation, but this day, Wednesday, June 22, he was cutting himself some slack. He’d bought tickets with bandmate and buddy Neal Marsh to see a favorite band, My Morning Jacket. He’d arranged with an assistant manager, Thea, to cover the desk starting at 1 p.m. He was going to crash on his couch for a solid nap, head to Hollywood late in the afternoon, meet his friend for some drinks, and attend the concert.

Josh was asleep when his phone rang about 3:30 p.m. He fumbled to answer the call. It was Thea, from the office across the street at the Embassy Hotel Apartments. She explained there was an FBI agent standing in the office who said he needed to talk to him. She said it was about one of their guests.

Josh, groggy, struggled to get his bearings. Thea’s voice sounded different, and he wondered what this could be about—an FBI agent?

The agent got on the phone and identified himself as Scott Garriola. He asked Josh if he was the manager of the building. Josh said yes, he was. The agent said he needed to come to the office. They needed to talk.

Josh couldn’t believe it. He asked, Can’t this wait until tomorrow? No, the agent said.

Josh noted firmness in the voice—no room for negotiation. He pulled himself to his feet and headed across the street into the hotel. He crossed the tiled lobby floor and went up the three steps to the tiny office on the left side. Thea, looking anxious, was in the office with FBI agent Garriola.

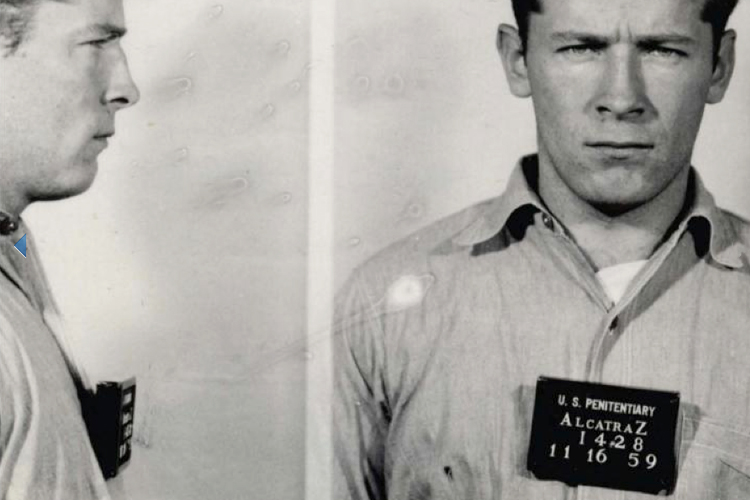

The agent had a manila folder. He told Josh he was there to check out a tip—a tip about a man who was possibly living in the Princess Eugenia, a man without a Social Security number, a bank account, and other identifying information. The agent then opened the folder to reveal the FBI’s fugitive flier for gangster James J. “Whitey” Bulger and Catherine Greig.

Josh stared at the two faces side by side. “Holy shit,” he said.

Reprinted from “WHITEY: THE LIFE OF AMERICA’S MOST NOTORIOUS MOB BOSS.” Copyright © 2013 by Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill. Published by Crown Publishers, a division of Random House, Inc.