It’s become something of a fad of late to apply neuroscience to partisan behaviors. A recent brain scan study distinguished the Republican from Democratic amygdala: The first is more driven by fear and reward, the latter by more generous-spirited emotional connectivity. In several books, the well-established linguist and cognitive scientist George Lakoff argues the basis for Republicans’ attachment to a rigid concept of paternalistic discipline and enforced obedience to an idealized authority.

Then there are last year’s two similarly inspired treatments: journalist Chris Mooney’s “The Republican Brain” and moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s “The Righteous Mind.” Despite their different training, both authors approach modern tribalism from a similar angle. Mooney wears his partisanship as a proud badge, making much out of the wider-ranging libraries of liberals and the inability of conservatives to accept science as an agent of positive change. Haidt, if liberal-leaning, steers a middle course, advising Democrats to “stop dismissing conservatism as a pathology and start thinking of morality beyond care and fairness.” In other words, you don’t have to endorse fear and loathing when you show compassion for the conservatives who reserve their compassion for the group of like-minded folks with whom they identify. There is, potentially, he says, a way to find common ground – and not just as there was when liberals joined with conservatives in the climate of fear after 9/11.

Welcome to the age of neuro-politics. More and more evidence suggests that genes, or brain chemistry, significantly influences one’s political perspective. So, conservatives sense danger sooner and more acutely than liberals – far more white Republicans own guns than do white liberals and blacks. But does the same ingredient in their makeup that makes them feel easily threatened really set them up to buy into conspiracy theories like, “The black president isn’t really American”?

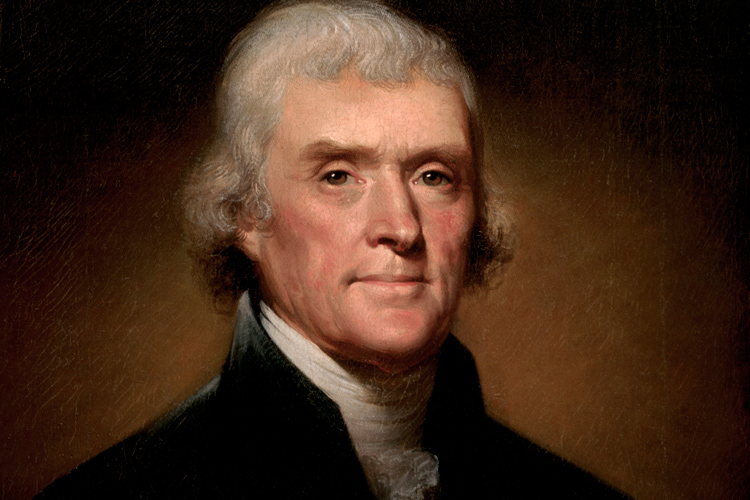

Hmm. How far back can we take this? Pretty far back, as it turns out. The theories privately put forward by Thomas Jefferson in attempting to make sense of his adversaries’ compulsion to resist what was then regarded as “democracy” (sympathy for the needs of the many) sound remarkably like an 18t-century version of George Lakoff and his disciples.

In 1795, Jefferson sought to intellectualize the immutable differences he perceived between those of his political party – keepers of the indomitable, forward-looking spirit of 1776 – and the conservative forces to whom George Washington had recently surrendered himself. For Jefferson, the Federalists’ resurfaced attachment to England demonstrated a preference for an unchallenged obedience to dying ideas. He called these people “Anti-republicans.” They included “speculators,” “office-hunters” and “merchants trading on British capital,” those who worshipped money power. On his side of the political spectrum stood optimistic small landholders and “the body of labourers” who understood freedom as a marketplace to which they had fair access.

Jefferson damned greedy conservatives as absolutists, “hoping monarchy might be a remedy if a state of complete anarchy could be brought on” first. What makes Jefferson a neuro-politician, though, is his conviction that the hardened Federalists he opposed were suffering from damaged brains, diseased minds, which rendered them incapable of supporting healthy social growth. Those who could only identify with money power were “nervous persons, whose languid [nerve] fibres have more analogy with a passive than active state of things.” He had not observed any amygdala under his microscope, but nonetheless concluded that the conservatives who feared a politics of openness tended to accept arbitrary power easily.

Federalists needed (and vocally demanded) order. Jefferson mocked their “timidity” and “delusion” in the face of the moderate democratization he proposed. He was convinced that the same weakness was reflected in their use of religious dogma as a crutch.Vocal ministers who labeled Jefferson an atheist intentionally mistranslated his statement that there was no harm done if Christianity-deniers claimed there were “twenty gods or no god.” His refusal to fear unorthodox belief caused shameless conservatives to insist that he would burn Bibles and superintend a complete breakdown of public morals if elected president.

To say there is such a thing as a “culture of the closed mind” may sound like an oxymoron, but is it? In historical relief, it is easy now to see Jefferson, despite his democracy, as closed-minded and self-protective in his pseudo-scientific assertions about African-American intellect. He felt certain his racial prejudice was objective, measurable and empirically derived. More open-minded others urged him to see what they saw, to no avail. And when it came to that monarchical persuasion he perceived among Federalists, he was so consumed by fear that even at the end of his life, long after the Federalist Party had died of its own accord, he warned of a “monocrat” resurgence in America.

Conservative tyranny. Liberal tyranny. Both have a long history in the political mind. At the Constitutional Convention, small states complained about large state tyranny. The states could not have come together as one were it not for the shared fear that dominated when they were militarily and economically weak. They had to surrender their competing claims to frontier lands to the federal government before any meaningful union could be arrived at.

As Lakoff has explained, the underlying battle is (as it has always been) rival understandings of the meaning of freedom. Is the common good best secured through the wider dissemination of opportunity and active pursuit of social justice (the liberal persuasion); or by the stronger enforcement of public safety through a locally derived, family-centered moral consensus (the conservative persuasion)?

But freedom from fear? Will stubborn, snobbish, clannish conservatives ever have the perfect world they crave? Aren’t bleeding heart liberals equally hopeless as they go out in search of others who feel what they feel? Politics exist because neither side’s definition of unsullied freedom will ever come to pass, and because compromise only succeeds when emotions align. We’ve divided ourselves into two national political parties, two simple ways of defining moral community. Reason is clearly not a competent opponent in its contest with the irrational.

That is why we have to have a federal government. Private enterprise and corporate culture do not exist to maximize the collective pursuit of happiness. They are meant to enrich some, and some only. Government was designed to promote balance among competing forces by applying laws equitably; to establish a common identity in spite of our cultural heterogeneity.

The states’ rights argument has proven narrow and limited. We see, for instance, how a state or locality will do nothing about inequality in educational opportunity, because the ruling group is content with the existing power and tax structure; or the education its core constituency receives allows for foot-dragging. Self-selected community makes it only natural to ignore the prospects of unseen, unknown, outlying poor communities. Someone has to think bigger, or we are not a nation. A fair-minded federal arbiter is needed to make adjustments. We see good effects emanating from the top, where government funds necessary research in science, health, and other critical fields.

Yet conservative Republicans decry big government largess and want Washington to stop spending, except on weapons systems. Typically ignoring what they themselves have received from big government, they translate liberal-minded fairness as a “giveaway” to those who aren’t doing enough for themselves. This is why liberals don’t get the “middle ground” approach. How do you negotiate with ideologues who refuse to see magnanimous government as a good thing? If you claim you’re pro-life, why aren’t you as demonstrably in favor of cleaning up the environment, ensuring public health, and everything else we want government to be proactive about?

Which brings us back to where this all began: what to say about the the fear of destabilizing change, extravagant openness, and surplus compassion, which liberalism represents to the conservative brain. Whether or not the divide between authoritarian moralism and magnanimous moralism is any more accurately understood today, with our advanced tools of neuroscience, than it was in Jefferson’s time, we must acknowledge that a simple, dualistic taxonomy of “liberal versus conservative” persists in our thinking about Americans’ political choices. Americans can’t pretend that class conditions have nothing to do with partisan identity; but often they do, and neuro-politics is another example of the phenomenon. Jefferson denied the slave-owning planter interest in the composition of his political party. There is much that we choose not to talk about; we find it easier to dismiss an “other” as fatally flawed.

Is tolerance the equivalent of naiveté, as a conservative thinks? Is intolerance intentional cruelty, as a liberal thinks? And do individuals belong only to one or the other persuasion? It would appear that we cannot become a free society if we are chained to a cognitive science that declares partisanship to be largely unconscious.