ONE OF NEW YORK’s most sophisticated galleries of interactive art used to be on St. Mark’s Place. And I do mean on St. Mark’s, out on the sidewalk. Itinerant street vendors would set up tables piled with the detritus of anonymous lives, cast off books, earrings, scarves, toy trucks, every item compressed under the weight of a small sadness. It almost seemed unkind to look, as if you were staring at a stranger weeping in private grief. But the collection of black-and-white photographs shoved under a table practically sang out its conspiratorial invitation: Complete me.

I’ll never forget the moment when, after fishing blindly in this box of a thousand dead memories, I pulled out a work of art. It had not been intended as one; it was just a snapshot. But it was aesthetically bewitched. The time it took for a shutter to open and close in, oh, I don’t know—a sheared-off sliver of one second in Depression-struck 1932?—was the exact amount of time it took the eye to remake it. A picture of a picture, this time taken by the beholder.

A group of eight children of varied age stands facing the camera, yet by the moment the light hits the film, each suddenly turns a different way. An older boy tries to rearrange the stance of the smaller girl in front of him, setting her face into profile, but he does not have time to remove his hands from her cheeks. Another looks away, as if into the past. All together they express the idea of suspended flux. The history of humankind, our longing to somehow mark in permanence the sense of our terrible impermanence, fitted into an area no larger than 3 x 4. They had no idea, these schoolkids or the invisible framer of this scene, that in another age an unknown viewer would see in their poses a classicism so timeless it might have come straight from the frieze of the Parthenon, and a vision of youth so fleeting it aches.

The genre of “found photography”—or, we might call it, inadvertent art—had a poignant moment in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. Some of the thousands of lost family photos reworked by seawater and sludge, wearing a perversely gorgeous sorrow, were exhibited in the New York Times, where they landed a punishing blow: no more immediate, or bruising, statement on loss was ever hung on museum walls. But to their separated owners, seeing this distress to the image must have been like making a short visit to hell. The receiver changes the meaning, not to get all Reception Theory on you. An international group of technically savvy volunteers began Operation Photo Rescue (“Insurance Doesn’t Rescue Photos . . . But We Do”) after Hurricane Katrina, and they are now working with infinitesimal patience to digitally restore pictures nearly destroyed in the later disaster. Stuff, even houses, can be replaced (with enough money), but every photo records something that can ever exist only within its frame. People who lost everything say they want their pictures back most of all. That’s because they are the mausoleums of life’s minutes, and it is as sacrilegious to let the roof fall in on the documents that proved we were there, that we lived in exactly this form, as to neglect a loved one’s grave.

But when we are gone, who is there to care, really? I cart the boxes of my paper ephemera through the years, from house to house to house, and I make sure not to store them in the damp basement. Someone will want these someday, I half-consciously think, because to think otherwise is to imagine I don’t really matter. Yet when I’m gone—meh. The brambles overgrow the headstone. And someone who happens on this sad and lonely scene will think, “Oh, man, cool!”

That I have been forgotten, then found in my forgottenness by a stranger, will give birth to an aesthetic thrill.

Umberto Eco had a term for this dyadic effect, which I and my fellow found-photography enthusiasts experience every time we find the unintentionally beautiful in someone’s wayward memories (there are some major collectors in the category, such as John and Teenuh Brown’s Accidental Mysteries and Rich Vogel of Foundphotos.net, who has a brilliant eye for the anonymous artistry to be found in our ceaseless wash of contemporary file-sharing). He called it “aberrant decoding.”

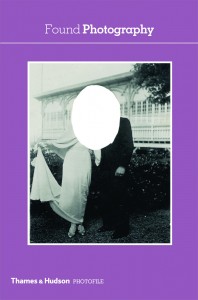

This week, a new addition to Thames & Hudson’s Photofile series—in France, Photo Poche, the Modern Library of compact photo books—lends new status to the relatively recent genre: Found Photography, with a suitably French introduction by Anne-Marie Garat (“This kind of photograph captures the underlying chaos that we always suspected was there, and by capturing it in a single moment, it reveals to us the radical otherness of visible reality”). On the cover is perhaps the most startling image in the collection, one of a subgenre that is especially jarring: what might be called excisionist works. Here an ostensibly elegant couple—c. 1940, the book says—poses happily. Except they have no heads. An oval has been cut out from the shoulders up. Perhaps to fit into an oval frame, where it still remains on the family mantelpiece. The “meaningful” part was retained, which left to us rag-pickers the useless throwaway to aberrantly decode: the effulgent mystery of what remains.

A new café and antiques shop has opened near where I live, its name echoing the melancholy shiver of the lost-and-found photograph: Outdated. A thousand important or inexplicable moments, in a dozen outdated formats (how many there used to be, one-inch thumbnails, postcards, Instamatics, Polaroids), lie tossed in drawers. I search through the zone of accident, and how many of those too were available to the amateur: mistakes of framing, exposure, fixative, cropping. Or time itself might work on the unstable chemistry of a picture, fading it to ghostliness or burnishing it to the surface density of a Dutch master. And maybe, as in the picture on the book cover, a new work might be made out of old through direct intervention, where a torn-away absence conveys all you need to know about the human heart. (I own a picture in which my Greek great-uncle stands, the peculiarly ecstatic joy of one who could only be in the presence of a beloved radiating from his sepia expression; then violence intrudes by way of a white scar running jaggedly along his left side. The woman I assume had been next to him has been excommunicated from the photographic embrace by my grandmother, I think, for apparently his girlfriend was married. If I did not know this exactly I could guess as much, since betrayal always comes to the same end. Ripped.)

Latte by my side, I work through piles of pictures. A small stack grows next to me on the couch; the ratio of good to bad is around 1 in 125. The ratio of great to good is 1 in 10. Over the hours, people stop and stare. “What are you looking for?” they venture at last. They think I’m looking for old relatives, or maybe pictures of sheep (a hundred years ago Dobbin, the milk cow, and the side yard chickens were documented as soberly as the children and grandpa with his new automobile).

“I can’t say, but I know it when I see it” is all I can reply, before they back slowly away. The aesthetic meter is not in the intellect, it’s in the body. It smacks you where you can feel it. Like Emily Dickinson said, “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.” When a picture is great, I feel as though someone punched me in the chest.

The mysteries of Europe

Found photography is not precisely art without an artist; instead, the artist is the one who selects, where the selection is an act of framing. In the game of found photography, the artist arrives long after the picture exists. Marcel Duchamp is the one who made it possible, with those “readymades” that scandalized the guardians of the status quo. Looking back on what he’d done in the second decade of the twentieth century he correctly appraised the works’ legacy: “I’m not at all sure that the concept of the readymade isn’t the most important single idea to come out of my work.”

Speechless

I slip quickly out of Outdated with my photos in my pocket, as if someone might belatedly realize they had just sold important work for pennies (more or less; as if to prove no one is really sure what discarded photos might be worth, on three separate visits I was charged three different amounts, from a dime to a dollar). Whenever I read about someone nabbing a Miró at a garage sale for five bucks, the first thing I wonder is how long and how hard the seller kicked himself.

Even though I was getting hungry, had been manically pawing through drawers for hours, it seemed certain a truly great picture, the one that would make me gasp, had to be in the bottom of the next. Or the one after that, for certain. I never tried crack for exactly this reason.

The thing about that picture I found on St. Mark’s Place: I would like to show you, except it’s lost again. I looked for it everywhere. It came with me through four moves, and now time itself has eaten it. The children pictured in it and the long-ago day it rose from the dead to my sight are both gone. This is the source of the disproportionate power of that photograph and those like it. In the confines of their small spaces, they convey the elemental story of what happens to us all: appearance, disappearance. And in between, the unexplained, the surreal, and the accident. Only at the end comes the loss, which for the picture at least holds the possibility of beginning again. In some other life.