Alexandra Aldrich grew up being told that she lived in a "child's paradise": a largely deserted, 43-room, 200-year-old house on 420 acres in the Hudson River Valley, complete with woods, animals, interesting outbuildings and bohemian tenants who made giant puppets and staged elaborate pageants. A twig on a branch of the fabled and wealthy Astor and Livingston family trees, Aldrich played dress-up in evening gowns her grandmother had worn to high-society events and wound a hand-cranked gramophone that was a personal gift from Thomas Edison.

She hated it. As Aldrich recounts in her new memoir, "The Astor Orphan," "I had always wished I could have grown up in a three-bedroom ranch house with employed parents, siblings, cable TV and functional cars." She might also have added "regular meals," since the pantry in her family's section of Rokeby, the ancestral mansion where her people have lived for almost two centuries, was often bare. If her father couldn't snag a free batch of rejected TV dinners from a nearby pie factory, he'd have to borrow money from the local gas station proprietor for groceries. Her mother, a solitary (and, by all signs, depressed) Polish fiber artist -- who had thought she was marrying into a wealthy urban clan -- would only shout from the kitchen, "You'll have to eat shit for dinner if you can't dig up any cash!"

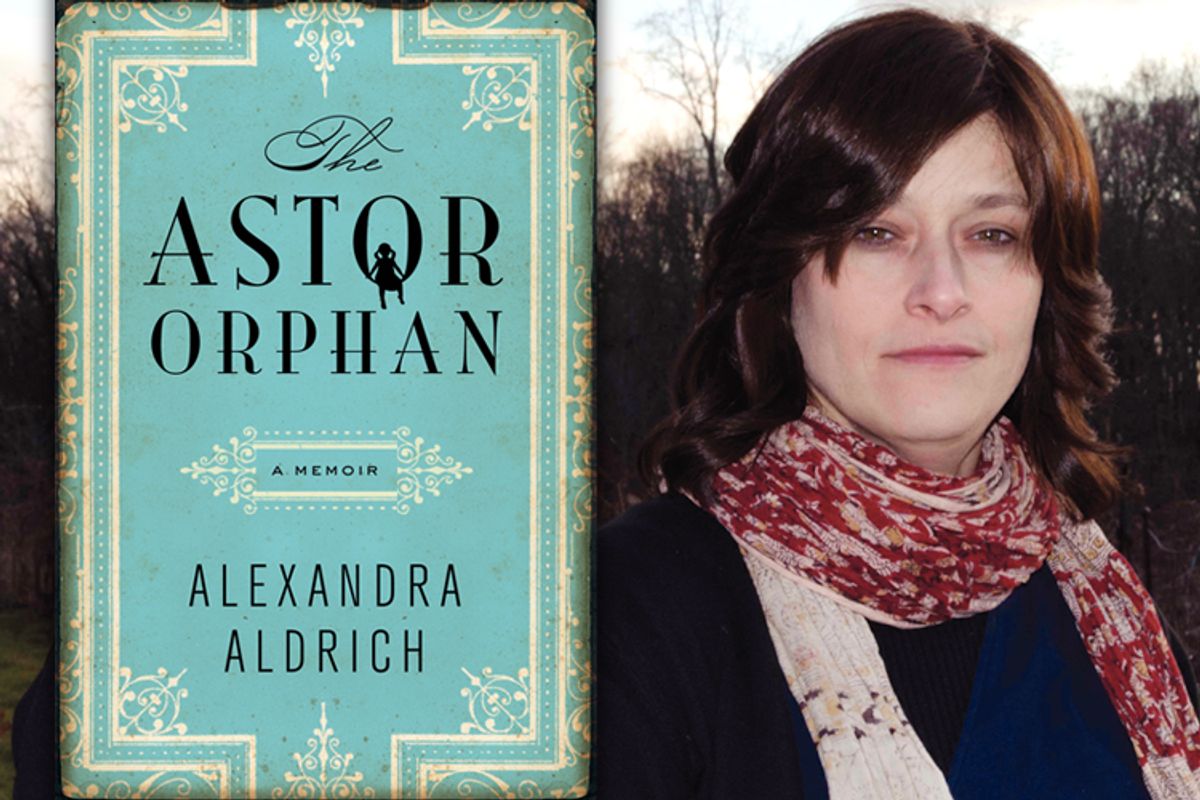

In premise alone, "The Astor Orphan" sounds like some delicious children's novel, the kind of thing you'd gobble a dozen times over by the age of 8. In reality it's a mournful, curious tale of an anxious child's longing for security. Aldrich, who kept a diary from an early age, apparently sticks closely to it; her book has a halting, episodic rhythm. It lacks the fluency of truly accomplished storytelling, but the story it tells is so extraordinary, and Aldrich's tone is so baldly honest, that the reader's attention will not flag.

During Aldrich's childhood, she lived with her parents in the former servants quarters of Rokeby: "We had been banished -- to the third floor. We lived in the eaves. We lived in poverty. Our lifestyle was irregular." Her father, despite an Ivy League education and five languages acquired while traveling in Eastern Europe (where he also found his wife), was never able to hold a steady job. Even a stint as a hospital orderly didn't pan out because he found it so difficult to abide by other people's schedules. Instead, he became a full-time tinkerer, working on the property, driving a backhoe around, adopting animals, taking in human strays and cadging stuff from friends, like his pal who ran the local funeral home and gave him items scavenged from the dead.

Elsewhere, in a more shipshape corner of the house, lived her uncle (her father's brother), and his wife and two daughters, Aldrich's cousins. Her uncle had a professional career, paid the property taxes and obsessively roamed the house by night, inventorying the antiques in cobwebbed rooms with buckled floorboards and strips of paper hanging off the walls. He worried that his brother's misfit guests would steal stuff. Although Aldrich found some refuge (and sustenance) in her uncle's quarters, her real sanctuary was with her grandmother, who lived a little ways off, in a converted garage. "She," Aldrich writes, "was the person who paid for and drove me to my violin lessons, bought my school supplies and clothes ... I clung to Grandma Claire as if to a life raft that both kept me afloat in the present and would steer me out of Rokeby in the future." Unfortunately, she also had a drinking problem.

While Aldrich fantasized of being adopted by an (imaginary) aunt in New York City, her everyday life at age 10 was likely to include being roped into strange art projects (she once played an esophageal muscle in a theatrical portrayal of the human throat), watching her mother (a "pagan" who "danced around bonfires on the summer solstice") hang and butcher a deer, trying to sober up her grandmother enough to get a ride into town, dodging a purported grave-robber named Walter on the stairway, and learning to drive the backhoe. She practiced her violin obsessively, dreaming of becoming a successful musician so she could "rescue" her mother, or at least get her attention for more than a moment or two.

Among the items Aldrich includes in "The Astor Orphan" is a heartbreaking schedule titled "What I Do All Day," drawn up when she was 7, with slots dedicated to homework, violin and piano practice and diary-writing, but also one that reads, "Watch 'Captain Kangaroo.'" Children who grow up in chaotic environments with adults who can barely take care of themselves often try desperately to assert some order in their lives. Aldrich also fretted about her inability to defend her father, a master of passive-aggression, from their other relations, who all blamed his "irregular" habits and inability to hold a job for the decline in the family fortunes.

Aldrich offers an unvarnished portrayal of herself as fierce yet also cowed, a grim little thing too aware of her family's precarious state to enjoy the freedom of her situation. She experienced "the sense that we lived on the brink of disaster" and "the sickening feeling that there was nowhere else in the world we could possibly belong." As she grew into her teens and formed some fragile relationships with classmates, she became, inexplicably, the target of bullies, who accused her of chasing a boy she didn't even know and called her a "little rich bitch."

The Astor legacy seemed inescapable; as Aldrich strikingly puts it, "money was the only thing we hadn't inherited." "The Astor Orphan" ends on a note of progress, but a tentative one at best. Surely it takes a mighty effort to throw off the burden of such a heritage or, on the other hand, to shoulder it effectively. I'm looking forward to learning, in a future volume, about the path she finally chose.

Further reading:

Read about Rokeby in recent years and see a slideshow of photos of the estate in a 2010 New York Times story.

Shares