Tom Hanks may have thought there was no crying in baseball, but as the summer of 1951 approached, the sport’s two most highly prized rookies were weeping.

Major league pitchers are a community within a community, and word quickly got around that 19-year-old Mickey Mantle had weaknesses. From the right side it was high fastballs, slightly up out of the strike zone, which for some unexplained reason he simply couldn’t lay off. From the left side it was low outside curves or other breaking pitches. Mickey began striking out — in bunches.

Mantle’s shyness had, up to this point, masked a ferocious temper. After striking out six times in a doubleheader in June, he began assaulting water coolers again, a serious enough offense when committed at Yankee Stadium, but downright unacceptable when it occurred in other ballparks around the league. After fanning twice against the St. Louis Browns, Mickey destroyed the cooler in the visitors’ dugout, much to the amusement of Hank Bauer and Yogi Berra, who did not truly understand how frustrated their new phenom was.

Yogi thought he could lighten the atmosphere with a joke. “Why are you so nervous?” he asked Mickey. Mantle mumbled that he wasn’t. “Then how come you’re wearing your jock strap outside of your uniform?” Yogi said with a grin. Mantle actually glanced down to see if it was true.

Mantle did not learn quickly from his early failures, but simply gritted his teeth and swung harder. He was pushing himself to the point of emotional strain to fulfill Mutt’s dream. Stengel began to lose patience with Mickey, not because he was striking out but because he was swinging at bad pitches. Casey was right about the bad pitches, but raised in an era when making contact with the ball was the hitter’s primary job, he did not understand — as many would not understand for decades — that the new game in baseball was power and that every home run Mantle hit was well worth the two or three strikeouts that it cost. But then, in the late spring of 1951, Mantle had also stopped hitting home runs.

Allie Reynolds tried to tell him about the virtue of choosing the right pitch to hit, of getting ahead in the count and forcing the pitcher to throw him something he could drive. It wasn’t that Mantle paid no attention to Reynolds, but that he was too young to translate Reynolds’s good advice into action. As Hank Bauer put it, “In the summer of 1951 we could see that Mickey wasn’t ready for the big leagues.” But, said Bauer, “it was just as obvious that in a short time he was going to be very ready.”

* * *

When Mickey Mantle came to New York, he was an unpolished hick. Willie Mays, who had already been to New York and played exhibition games in the Polo Grounds with the Black Barons, headed for the big city having actually seen some of America. Mickey arrived in the city in a suit that looked like it came from a road company of L’il Abner; Willie had been given grooming tips by several vets and, at least in comparison to Mantle, looked as if he had stepped out of a production of “Guys and Dolls” (which, starring Robert Alda, was one of Broadway’s biggest smashes in 1951). On the plane, Willie put his cap and glove (practically all he’d had a chance to grab before leaving the Millers) on the seat next to him. A stewardess asked him with a smile, “Are you Jackie Robinson?” Willie beamed and said no, but he was going to play for the New York Giants and would soon be playing baseball against Jackie. When he arrived in Manhattan on May 25, the Giants were playing under .500 ball and were so far behind the Brooklyn Dodgers that Mays couldn’t help but wonder, “What do the Giants need me for?”

After a cab ride from LaGuardia to the Giants’ front office, an ebullient Mays shook hands with Doc Bowman, the Giants’ trainer, and Eddie Brannick, New York’s traveling secretary, who presented him with his contract. Without hesitation, Willie, his hand shaking with excitement, signed for $5,000. Brannick put his hand on his new player’s shoulder and hurried him out the door for the train ride to Philadelphia, where the Giants were playing the Phillies.

Bowman went out of his way to make Willie feel that the team was looking out for his interests — Monte Irvin, he told Willie, was going to be his roommate. Irvin, like Mays, had been born in Alabama, although he’d grown up in Orange, New Jersey, right outside Newark. He was 12 years older than Mays and knew him from barnstorming exhibitions, games Willie recalled fondly because he had made more money from them than he had playing for the Giants’ farm team in Trenton.

Mays’s first connection to his big league team involved none of the anxiety that Mantle had experienced. When he got to the team’s hotel in Philadelphia and knocked on his door, he was greeted with “Hi ya, roomie. Does Skip know you’re here?” A smiling Irvin brought him to Durocher’s room; it was the first time in Willie’s life he had seen a hotel suite. His eye took a quick inventory: This was only a weekend series, but the closet was stuffed with his clothes and shoes. Leo definitely liked the finer things in life.

“Glad to see you, son,” he said. “Glad you’re hitting four seventy-seven.”

“He might have made players nervous with his style, but he made me relaxed right away. I see now what he did. He buttered me up.”

At Shibe Park, Mays was surprised to find the Giants clubhouse quiet — but when you’re in fifth place, he reasoned, there wasn’t too much to talk about. His locker was next to Irvin’s. He looked inside and saw for the first time the shirt with the number millions of baseball fans around the world would come to associate with him, 24. “Son,” Durocher told him, “you’re batting third and playing centerfield.” Willie was dazzled. “That sounded to me like something DiMaggio might be doing … You don’t put a man up third unless you think he’s your best all-around player. In centerfield — I guess of all the fielding positions on a team — that has always been the one filled by a player who can lead the team, take charge, make plays. I just couldn’t believe this was happening to me.”

* * *

Mays’ teammates liked him, the fans adored him, and to the veteran New York sportswriters he was the black son they never had. But if Willie thought he was going to cruise through his rookie season, he soon discovered there were obstacles he hadn’t yet considered. One of them was a pal from the Negro Leagues he had barnstormed with.

Frank Forbes was a successful black boxing promoter who had worked for and with most of the prominent black fighters of his era, including heavyweight champions Ezzard Charles and Jersey Joe Walcott, as well as the most popular and the greatest pound-for-pound fighter of his and perhaps any other time, Sugar Ray Robinson. Having staged bouts at the Polo Grounds, Forbes had built a good working relationship with Horace Stoneham and the New York Giants. It was no surprise, then, that the Giants turned over the care of their most valuable young property to Forbes. Forbes was offered a business relationship by the Giants: If he would find a safe place for Willie to live and keep a close eye on him, he would be allowed to share in promotions Mays did with the organization.

Through Forbes, Willie met the leading black celebrities of his day such as Robinson and Joe Louis, who had been heavyweight champion for all of Willie’s formative years; he also met entertainers like Billy Eckstine and Dizzy Gillespie, who were as thrilled to be around the Giants’ budding young superstar as he was to be in their presence. Monte Irvin recalled a breathless Willie phoning Cat Mays back in Alabama, saying, “Pop, you’re not going to believe this, but I just met Duke Ellington. He came to the game last night.” In fact, Cat had met Duke Ellington when he played with a small combo at Bob’s Little Savoy in Birmingham sometime in the mid-1930s.

Forbes told Time magazine in 1954, “When I first met Willie, I thought he was the most open, decent, down-to-earth guy I’d ever seen — completely unspoiled and completely natural. I was worried to death about the kind of people he might get mixed up with.” It was assumed, of course, that Mays would be living in Harlem, a place Forbes found to be “full of people just wanting to part an innocent youngster from his money. Somebody had to see to it that Willie wasn’t exploited, sift the chaff from the flour, figure out who was in a racket and who was in a legitimate organization.”

A cousin of Cat’s who lived in Harlem offered Willie a room with his family, but it was crowded and noisy, with Willie’s distant cousins going in and out at all hours. Willie, thought the Giants and Forbes, needed a “good home environment” — meaning not surrounded by family. Through his own contacts, Forbes found David and Ann Goosby on 155th Street and St. Nicholas Place — or about three good Willie Mays pegs from the Polo Grounds. Mrs. Goosby cooked regularly for Willie, did his laundry, and, with Forbes’s help, looked after his every need as no one had done since Willie left Fairfield and Aunt Sarah.

“Willie’s a good boy,” Mrs. Goosby told a reporter from Time, “and all I have to lecture him on besides eating properly is his habit of reading comic books. That boy spends hours, I swear, with those comics.” If only Willie had been playing for the Yankees, he and Yogi Berra could have shared their stacks of comics.

Forbes, in turn, enlisted Monte Irvin’s assistance when it came to outfitting Willie and showing him the best restaurants and places to go. Irvin not only was older than Willie but had grown up in a much more sophisticated environment. “He was such a countrified boy,” Irvin told me, “that he had to be shown just about everything, but he learned very, very quickly.” Irvin was joking just a bit; Willie was not a country boy. He never rode a horse to school, as Mickey Mantle had. But nearly all young black ballplayers from the South received some ribbing from the older players, particularly those who had grown up north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Forbes and Irvin felt they had to protect Willie from women. After each Giants home game, the players would find dozens of females waiting at the exit gate, supposedly looking for autographs but, according to Irvin, “really waiting to give Willie their autograph as well as their phone number.” Sometimes, after a day game, Irvin would take Willie out to dinner, and Willie would empty his pockets of all the notes he had collected when leaving the ballpark. “I assumed that none of these girls was up to any good,” said Irvin, “and in the course of our conversation, when Willie wasn’t paying any attention, I’d crumple them up and throw them away.” Sometimes Irvin would find notes from hustlers who wanted to act as Willie’s agent “for commercial deals.” Irvin tossed those messages away as well. Any legitimate businessman, he felt, would approach Willie through the ball club. Mickey could have used similar guidance from the New York Yankees.

* * *

Like all New Yorkers, Mickey had to learn to use the subway. On his first underground trip, he asked someone how to get to the ballpark. The fellow, who did not recognize Mantle, told him, No problem, just take the Lexington Avenue Express and get off at 161st Street. Mickey managed to end up on the wrong train and wound up instead at the Polo Grounds, where he heard clusters of happy Giants fans. He asked them what they were celebrating; they told him that the Giants had just beaten the Cincinnati Reds on a home run by their great new rookie, Willie Mays. Once he figured out what had happened, in a panic, he jogged over the Macombs Dam Bridge until he reached Yankee Stadium. After that, he mostly got around by cab.

Some nights were lonely. Mickey went to the movies as often as he could, catching noon shows when the Yankees had a night game or late shows after day games. “I usually sat in a last row balcony seat, alone, checking my watch because the rules were that you had to be suited up and ready for batting practice three hours ahead of time.” His favorites, of course, were Westerns. Since they were also the favorites of Willie Mays, and since Willie’s favorite spot was the balcony, and since many uptown New York movie theaters were integrated by the early 1950s, Mickey might well have been sitting close to Willie in the dark without knowing it. Or he may have passed Willie on the way in or out, as the Giants occasionally scheduled a day game in New York on days the Yankees were playing at night — and vice versa.

Some nights he was not alone. “Around that time,” he would later say in a memoir, “a very pretty showgirl named Holly came into my life.” Perhaps he met her in the balcony of a movie theater, or at the Stage Deli, eating a reuben sandwich. “Once in a while when the team was in New York and I had the evening free after a day game, we’d go out for dinner or Holly would hang out with me at the apartment on Seventh Avenue. I guess I developed my first taste for the high life then — meeting Holly’s friends, getting stuck with the check at too many fancy restaurants, discovering Scotch at too many dull cocktail parties. It was a lot of fun — while it lasted.”

It didn’t last too long, but it was long enough to get him into quite a bit of trouble. He would later claim to have met his first “agent” through a phone call — somehow the man got his phone number and woke him up early one morning to tell him of a “golden opportunity” he had for him. Before Mantle had finished brushing his teeth, a “short, chubby guy with a razor-thin mustache” was at his apartment with two contracts. One was for personal services, for which Mickey signed away 10 percent of all his earnings outside baseball for 10 years; the second, for two years, gave the “agent” 50 percent of Mickey’s endorsements, testimonials, and appearances.”

“You don’t have to sign till you see a lawyer,” the agent reassured him, and of course, he had a lawyer to refer Mickey to. It strains credulity to think that Mantle signed the contracts. Where were Mickey’s roommates to advise him on this? And why didn’t Mickey, who consulted the Yankees and/or his father on nearly everything, ask someone else for advice? The answer is probably that Mickey trusted Holly. Shortly after meeting the shyster agent, Mickey found out that the man was “somehow” acquainted with her and had “sold” her 25 percent of his interest in Mickey’s earnings.

In his various memoirs, Mickey never identified the man, but six years later, when Holly told her story to a scandal mag, his name was revealed as Alan Savitt. By all accounts, he seemed to be a road-show version of a Damon Runyon character. He promised to get Mickey endorsements, personal appearances, even movie deals: “The sky is the limit, trust me.”

* * *

Had Willie Mays not blossomed into one of the greatest players ever, it’s doubtful that writers would have later made the case that he was the major spur to the Giants’ incredible comeback during the last two months of the 1951 National League pennant drive. Most of the writers who made that case, most notably Charles Einstein and Arnold Hano, both of whom later wrote books on Mays, took their lead from Monte Irvin, the Alabama-born, New Jersey–raised star who became Willie’s biggest booster on the Giants. “I believe to this day,” Irvin told me in a 2009 interview, “that the main reason we made up those 13 games [from the beginning of August] and caught up to the Dodgers and won that playoff was Willie. He just made everything seem better, more fun.”

Like Crash Davis says in Ron Shelton’s great baseball film Bull Durham, “The reason you think you’re winning is the reason you’re winning.” But coming down the stretch in 1951, there were lots of reasons for the New York Giants to believe that they were winning, beginning with Monte Irvin himself. Irvin, who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1973, did not make it to the major leagues until the end of the 1949 season, when he was already 30 years old, but in 1951 he hit .312 with 24 home runs and a league-leading 121 RBIs. According to Bill James’s complex Win Shares method, which awards players points for every offensive and defensive contribution, Irvin was the Giants’ most valuable player in 1951, followed closely by pitcher Sal Maglie, shortstop Alvin Dark, outfielder Bobby Thomson, pitcher Larry Jansen, shortstop Eddie Stanky, catcher Wes Westrum, and then Willie Mays.

Which is not to deny that Mays made contributions that could not be measured by cold statistics. His teammates, black and white, loved him; his joy in playing the game was contagious, a quality much appreciated during those tense late-summer weeks of the pennant race as the Giants fought furiously to overtake the hated Dodgers. The press loved him too. As with Yogi Berra, they were amused by Willie’s love of comic books and loved his famous habit of calling out “Say hey!” even if the phrase appeared in their stories much more often than Mays said it in real life.

It was during the heat of the pennant race that the myth of Willie Mays the innocent gained popularity as sportswriters referred to him as a “country boy” — though he had grown up in an industrial suburb and near the South’s greatest industrial city. Mays’s most recent biographer, James Hirsch, thinks that Willie, at least in this period, was “good-natured, shy, naive … untouched by cynicism. Mays all but shouted out his vulnerability.” Hirsch also maintains that Willie was “unschooled in city life,” but this is open to question. Willie knew Birmingham and its Fourth Avenue black culture fairly well, and by age 19 he had not only barnstormed through many of the South’s biggest cities but had been to New York and seen Harlem up close. Mickey Mantle at the same age was not half so schooled in city life, though he proved to be a quick study.

Still, that’s the way New York sportswriters wanted to see Willie, and that’s the way the fans still remember him. Willie’s popularity propelled him into his first award. Not that his contributions as a rookie didn’t merit recognition. Roger Kahn admits, “We [the New York sportswriters] knew by the end of the season we were going to lobby for Willie as Rookie of the Year. He was just too damn popular not to win it. But looking back on it, I think we made the right decision.” They did. Despite his lack of Triple-A experience, Mays hit, in his first 121 big league games, a respectable .270 with 20 home runs and 68 RBIs, and his hitting was arguably even more impressive than that: After getting just one hit in his first 25 times at-bat, he hit nearly .290 for the rest of the season. If he was not the primary cause of the Giants’ incredible surge, he was certainly the embodiment of it.

Fate spared the 20-year-old Willie Mays one huge test: In Game 3 of the National League Championship Series, when Bobby Thomson hit his immortal ninth-inning home run off Ralph Branca, Willie was kneeling in the on-deck circle. In the clubhouse after the game, Durocher walked over to Mays with a big smile on his face and told him he was surprised that, with the bases loaded, the Dodgers’ manager, Charlie Dressen, hadn’t had Branca walk Thomson and pitch to the rookie. “I’m glad he didn’t,” Mays replied. “I didn’t want the pennant hanging on my shoulders.” In truth, Mays had a terrible playoff — 1-for-10 in the three games, striking out three times and making an error in the outfield. In the biggest game of the season, he was 0-for-3 at the plate.

Champagne corks went off in the Giants’ clubhouse like firecrackers on the Fourth of July. Willie had his first taste of champagne — it was the first alcohol he had taken since Cat forced him to try some Jack Daniels back in Fairfield. He got sick and never drank champagne again. A few days earlier, when the Yankees had clinched the American League pennant, Mickey Mantle, not yet 20, and egged on by his new pal, a utility infielder named Billy Martin, had drunk a bit too much champagne. He loved it.

The 1951 New York Yankees needed no ninth-inning playoff miracles to win their pennant, finishing five games ahead of the Cleveland Indians in the American League. Back from the minor leagues in Kansas City, Micke Mantle resumed his play in right field and did just fine the rest of the season. In 96 games, he hit .267 with 13 home runs and 65 RBIs, just three fewer than Mays, who had batted 123 more times.

The day after Thomson’s home run, the emotionally exhausted Giants prepared to face the Yankees in the Bronx. Two baseball fathers, Mutt Mantle and Cat Mays, who would never know how much they had in common, were at Yankee Stadium to watch the first World Series game either had ever seen in person. (They had had the thrill of their lives the day before at the Giants-Dodgers playoff game at the Polo Grounds.) When an exuberant Willie emerged from the visitors’ dugout, he was stunned. “I saw Joe DiMaggio for the first time … I spotted him on the field surrounded by reporters, but I was too shy to go up and introduce myself. A photographer came over to me and asked if I would pose with Joe for a photo. ‘Why would he want to take a picture with me?’ I asked. The photographer brought me over and introduced us. I got the chance to talk with him for just a few minutes, a dream come true.” Willie had no way of knowing it, but the couple of minutes he chatted with his idol was probably more time than Mickey had talked with Joe all season long. “That was the only time I got to see my boyhood hero play. And it was the only time when we posed for pictures when we were both playing.

“There was another ball player there, though, with whom I was destined to be compared over the years — Mickey Mantle … even though he was the rightfielder in 1951, he was going to be the centerfielder for many years to come … He was the lead-off batter in the series. As luck would have it, I had an effect on his career.”

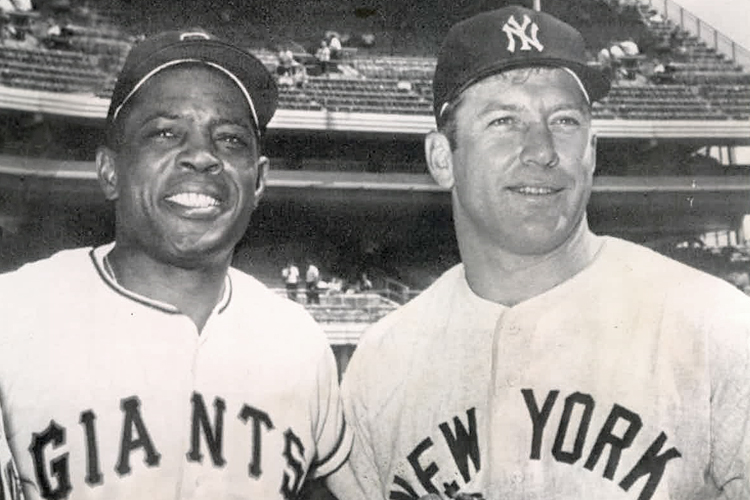

A good hour and a half before the first pitch, someone thought it would be a great idea to bring the two teams’ celebrated rookie outfielders together for a photo opportunity. And so Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays, the purest products ever produced by baseball, met for the first time and, bats on their shoulders, grinned like the schoolboys they practically were.

Mickey, a wad of bubblegum stuck in his apple cheek, grinned while Willie, still exuberant despite the apocalyptic playoff series with the Dodgers, joked with the photographers. They had, of course, heard of each other: Mays had been seeing Mantle’s name in the sports pages since spring training, and Mantle had heard of Mays from Minneapolis Millers players and coaches during his brief visit to Minneapolis with the Kansas City Blues. “When I was up there,” Mickey told Roger Kahn years later, “that’s all I heard about. ‘You should see Willie Mays field, you should see Willie Mays hit, you should see Willie Mays run the bases.’ It was the first time I heard something that I was going to hear quite a bit over the next decade: ‘Boy, I hope you turn out to be half the ballplayer Willie Mays is.’”

Had they known each other a little better, or if Mickey had not been quite so shy, they would have had much to discuss: their love of Westerns, their enthusiasm for shooting pool and having a father for a baseball coach. But the two rookies, both understandably awed by being at the World Series in New York, smiled, shuffled their cleats, and said little to each other.

Roger Kahn recalls his colleagues mumbling questions to each other such as, “Is Mantle a little broader across the shoulders?” and “You think Mays’s forearms are bigger?” and “Who’s supposed to be the fastest?” (the consensus at the time was Mays) and “Who do you think would win a home run contest?” An unknown photographer snapped several shots of Mickey and Willie together, after which they laughed, shook hands, and went back to their locker rooms.

Having finally brought them together, the forces that had shaped their lives and careers seemed almost at once to erase the paths that had brought them there, as if to guarantee that their likes would never be seen again. The Negro League World Series that Willie had played in just three years before had ceased to exist; the Negro Leagues themselves were rapidly fading. So too was the highly competitive, finely tuned minor league farm system that Mantle had come up in; though it would produce many more fine players, Mickey would be the last superstar nurtured in the Yankees’ minor league network. And within a few years, the world of industrial league baseball that had honed their skills at such an early age would all but disappear from the American landscape.

In Game 1 of the World Series, the rookies were a combined 0-for-8 as the Giants won, 5–1. The next day the Yankees came back to win, 3–1, though Willie was once again hitless while Mickey got his first World Series hit in two at-bats and scored a run. In the fifth inning, with the Yankees leading 2–0, Willie lofted a fly ball to right-center — not the pop-up it has often been described as but a fairly good shot that, had it gone perhaps another 10 feet, might have been in the gap for an extra-base hit. Casey Stengel had told Mickey to run down fly balls hit in that area because “the Big Dago can’t get there anymore.” But DiMaggio did get to this one and called Mantle off. Mickey caught his cleat on an open drainpipe as he stopped, tearing up his knee and forever destroying the possibility that he would be the greatest player baseball had ever seen.

For many years Willie Mays made no mention that he had been the one who hit the fateful fly ball. Charles Einstein, who would come to know Willie better than any other writer, was of the opinion that Willie simply didn’t know what he had brought about until another writer told him about it several years later. But by 1988, Willie — or at least his co-author Einstein — seemed to have a complete memory of what had happened: “From that day on, Mickey seems to be marked with a sort of pity; people were forever saying ‘Just think what he could have done if his knees weren’t bad.’ But Mickey had a great career anyway. Nonetheless, I felt bad about the accident.”

It’s possible that an unknown Yankees groundskeeper, the man who left the drain uncovered, committed one of the most devastating errors in the annals of baseball. And Willie Mays was an unknowing assistant.

Reprinted from “Mickey and Willie” by Allen Barra. Copyright © May 2013. Published by Crown Archetype, a division of Random House, Inc.