As conservatives gained power and confidence in the decades after Barry Goldwater’s defeat, each of the three political tributaries whose convergence fueled the movement—anticommunism, antitaxation, and the Religious Right—could claim the “Battle Hymn” as a call to arms. The song resonated with the Manichaean proclivities of cold warriors, who regarded America’s confrontation with the Soviet Union as an ultimate battle, waged in the shadows of nuclear brinksmanship. Even as it addressed contemporary anxieties, the song also conjured up an idyllic American past, one in which traditional values thrived, untroubled by an intrusive federal bureaucracy. Finally, the hymn spoke to the growing electoral clout of evangelical Christians, who had shed the political alienation encouraged by fundamentalism and begun to stride unabashedly into the political arena; it became, for instance, a staple at anti-abortion rallies and was frequently played at protests against the government’s banning of prayer in public schools.

A premillennial perspective animated this newly charged political activism. Many of the denominations whose members made up the Religious Right foretold Christ’s imminent return and rejected the postmillennial vision of the world’s progressive salvation through man’s benevolent striving. Once, this attitude had led to political quiescence, but in the final decades of the century it led to a sense of heightened urgency. The martial images in the “Battle Hymn” helped to reinforce the premonition that the forces of the adversary were closing in.

In fact despite its heterodox theological foundations, the “Battle Hymn” became a rallying cry for the religious orthodox protesting the inroads of secularism, atheism, and religious liberalism in American culture. Liberals and conservatives within denominations had clashed before over the liturgical meaning of the “Battle Hymn,” yet the terms of the debate had now changed. In the early 1960s, for instance, when the United Methodist Church initiated a revision of its hymnal, opposition to the inclusion of the “Battle Hymn” came from Southerners, who still resented the Unionist associations of the song. When the denomination began a revision two decades later, in May 1986, Northern liberals led the opposition. Fired by the campaign for nuclear disarmament in the wake of the Chernobyl power plant disaster, they sought to remove “Onward Christian Soldiers” and all but the chorus of the “Battle Hymn” from hymnals because of their “unrelenting use of military images.” They hoped to counterbalance what they considered to be an overly masculine and aggressive divinity with feminine metaphors for God and to correct sexist and racially insensitive language with more inclusive terms.

The proposed changes infuriated the more conservative within the denomination, who charged the revision committee with being anti-American, “soft-headed,” Communists, and “liberal ignoramuses.” In July the hymnal commission received over eleven thousand letters, only forty-four of which supported the proposed revisions. So many protest phone calls flooded the denomination’s headquarters in Nashville that for nearly two weeks the staff had to make outgoing calls from a public payphone in the lobby. Overwhelmed by the response, the committee ultimately decided to restore the two controversial hymns (though they added an extra stanza to “Onward Christian Soldiers” clarifying that the enemy to be combated was Satan). Their decision met with wide acclaim; even the New York Times called the committee’s initial revision “the liturgical equivalent of changing the formula for Coke” and applauded them for reversing the move.

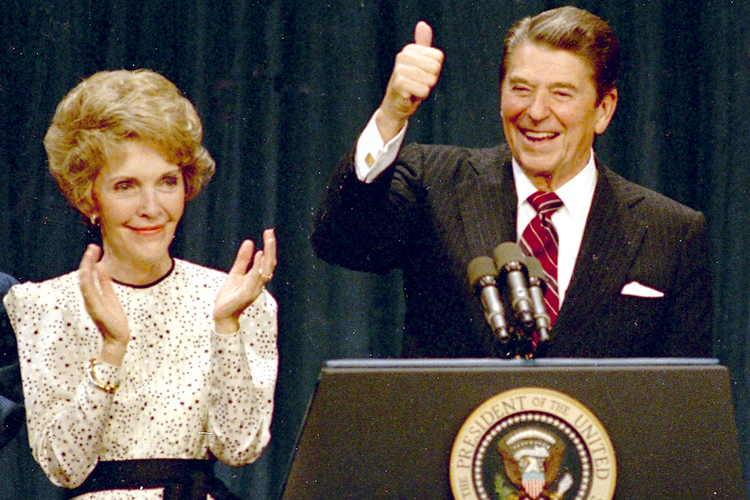

It is no coincidence that the man who synthesized the various strands of conservatism most expertly was also the national leader most closely identified with the “Battle Hymn” since Theodore Roosevelt. On multiple occasions Ronald Reagan declared the hymn his “favorite song,” and it threaded its way through his ascent to the presidency. Early in his career, when he served as a “traveling ambassador” for General Electric, giving patriotic (and pro-corporate) speeches at the company’s plants throughout the nation, Reagan often spoke to the musical accompaniment of the hymn’s tune. A high school band played the “Battle Hymn” at Reagan’s inauguration as California’s governor; the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, massed in front of the Lincoln Memorial, sang the hymn during his presidential inauguration; and the U.S. Army Chorus performed the song at his funeral.

Reagan’s critics associated his fondness for the hymn with his ties to political and religious fundamentalism. It was, to them, an anthem of immoderacy. An ally of Gerald Ford, who battled Reagan for the Republican presidential nomination in 1976, urged Ford to give up courting the right wing of the party. “We’re never, never going to get those crazies back with us,” he told the New York Times. “They’re going to march down the street with Reagan singing ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic.’”

Reagan’s relation to the hymn was more complex, however. The tension between those millennial hopes and apocalyptic fears reflected his own bifurcated personality, as genial eschatologist and cheerful cold warrior. The song clearly fed his predilection for moral absolutes, his commitment to ultimate victory over an “Evil Empire,” and his fascination with end times. His apocalyptic views and their connection to his nuclear policy in fact became a point of controversy during his presidency, especially after his secretary of defense, Caspar Weinberger, insisted that his reading of the Book of Revelation convinced him that “time is running out” and his nominee for secretary of the interior responded to questions about preserving the environment for future generations by insisting that he did not know “how many future generations we can count on before the Lord returns.” Reagan had previously suggested a similar intuition of the end’s imminence and had once explicitly linked Armageddon to nuclear catastrophe, a common association in fundamentalist prophecy writing of the period. As he told a lobbyist for Israel in 1983, he often wondered whether this generation would not become the one that would witness Armageddon. The prophecies in Revelation “certainly describe the times we’re going through,” he remarked. Critics grew concerned: in the nuclear age, might such a fascination with end times represent a self-fulfilling prophecy?

Reagan deflected the uproar generated by such comments by insisting during one 1984 presidential debate that he held a merely “philosophical” interest in the Apocalypse and had no idea when it might actually arrive. (That it would arrive, he did not seem to doubt.) Improved relations with the Soviet Union helped to quell the controversy. So too did the fact that Reagan’s own overpowering optimism frequently eclipsed his doomsday streak; his faith in America’s promise mitigated whatever terrors might attend the coming of the Lord. In fact he seemed to appreciate the “Battle Hymn” primarily as an expression of patriotism and traditional conservative values, not as an expression of prophecy. “Nothing thrilled me more,” he recounted in his autobiography, “than looking up at a wind-blown American flag while listening to a choir sing ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic,’” hardly a vision from Revelation.

Conservatives secured their appropriation of the “Battle Hymn” as the movement’s partisans increasingly clothed their various policy preferences in the language of freedom, making the hymn’s final stanza a catch-all anthem for their religious and ideological enthusiasms. This emphasis on freedom as the cardinal value pointed to the possibility of some common ground with progressives. However, as progressives increasingly ceded the rhetoric of freedom to the Right, favoring instead a political discourse centered on rights, emancipatory exhortations were more often wielded as instruments of partisanship. The same might be said for the “Battle Hymn” itself. Unsurprisingly the hymn played a leading role in one of the ceremonies of the Right’s ascendancy, the installation of Newt Gingrich as speaker of the House in January 1995. That morning Gingrich had joined his congressional colleagues at a Capitol Hill church. The service had featured readings of biblical texts calling for reconciliation and peace and concluded with a black choir performing a stirring rendition of the hymn. Later that afternoon, after his swearing in, Gingrich referred to the song in the peroration of a lengthy address in which the partisan incendiary proclaimed his commitment to bipartisanship. Speaking within sight of the Lincoln Memorial, Gingrich remarked, it was hard not to appreciate “how painful and how difficult that Battle Hymn is.” It called on Americans to accept a sacred charge, expressed in its last lines, “As he died to make men holy, let us live to make men free.” Gingrich gave that final word an expansive meaning that he hoped might appeal to both Republicans and Democrats: “If you can’t afford to leave the public housing project, you’re not free. If you don’t know how to find a job and you don’t know how to create a job, you’re not free.” He called on his fellow congressmen to find an inspiration in those verses for nonpartisan public service.

Of course, those verses could yield other, less pacific interpretations as well, hinted at by the fact that, before the day was done, the new speaker had found an opportunity to denounce Democrats as “cheap, nasty and destructive.” For much of the next decade, Democrats were more often treated as antagonists than as allies in the struggle to make men free. In July 2001, for instance, during a congressional debate over an amendment that would prohibit the “physical desecration of the flag of the United States,” John Duncan Jr., a Republican representative from Tennessee, invoked the “Battle Hymn” and quoted its final stanza. In doing so, however, he transformed an abolitionist hymn into a libertarian call to arms, one in which Democratic supporters of an enlarged federal government were paired with foreign totalitarian despots. “[The hymn’s final lines are] what so much of what we do today is all about,” he declared. “The battle or the struggle for freedom is ongoing. It is never ending. There are always tyrants and dictators from abroad who would take our freedom away if they had the slightest chance to do so, and there are always liberal elitists and bureaucrats from within who want to live our lives for us and spend our money for us and take away our freedom, slowly but surely.”

Just a few months later the sight of the crumbling Twin Towers and the smoldering Pentagon muted much of that divisiveness. The response to the 9/11 attacks, including the service at Washington National Cathedral, brought to the fore those strains of the “Battle Hymn” that promoted national unity in a time of crisis. The song affirmed a core of values and a tradition of sacrifice that inspired and consoled Americans of all backgrounds and stations. Yet, as we have seen, the consensus that the song fostered was always tenuous, and the hymn continued to unleash forces that threatened to sow divisiveness even as it celebrated unity.

Such tensions were on display in April 2008, when Pope Benedict XVI became only the second pontiff to visit the White House. The White House organized the largest welcoming ceremony in its history, with over 13,500 guests on hand, who spontaneously serenaded the pope (who turned eighty-one that day) with a version of “Happy Birthday.” In his remarks President George W. Bush linked the nation’s struggle against Islamic terrorism abroad with the campaign to abolish abortion at home and with broader struggles against moral relativism flaring up throughout the West (and in doing so, seemed to lump Democratic defenders of reproductive rights with terrorist militants). The ceremony concluded with a rousing four-part arrangement of the “Battle Hymn” performed by the U.S. Army Chorus, whose members shouted out the final lines with a startling staccato vigor.

Many conservatives applauded the event, interpreting it as a worthy gesture in support of ecumenical orthodoxy and as a savvy effort to cement the growing political alliance between evangelical Protestants and Catholics. Special attention was focused on the “Battle Hymn.” “[It is] a patriotic, yet spiritual song, uniquely American, that we know the Holy Father will enjoy,” one White House aide explained. Conservative talk-show host Rush Limbaugh was so impressed with the selection—“God’s music,” he called it—that he played the song on his radio program for weeks afterward. It represented, he informed his listeners, a vigorous effort to reinstall God in the public sphere and an unembarrassed articulation of American exceptionalism. When President Bush called his show a few days after the White House ceremony, Limbaugh gushed that the performance of the hymn had “stirred” his soul: “It was so uplifting. It was so timely.”

But some Catholic observers expressed discomfort with the choice, which they interpreted quite differently. The Vatican had, after all, honored its traditional commitment to pacifism by opposing the Iraq War, with then-Cardinal Ratzinger (soon to be Pope Benedict) expressing his skepticism of America’s justifications for the invasion. Some had hoped that the pope would use his visit to the United States as an opportunity to reaffirm publicly the vocation of peacemaking, yet except for a brief call for “the patient efforts of international diplomacy to resolve conflicts” and a passing paean to the United Nations, he was pointedly restrained on the subject. Indeed while some interpreted the selection of the song as a militaristic affront to His Holiness, the request for the “Battle Hymn” had come from the Vatican itself. When the White House asked if there were any songs the pope would like played at the ceremony, his American representative mentioned the one with the “Glory, glory Hallelujah!” chorus. By the final verse, the pope could be seen faintly mouthing the “Hallelujah” refrain with the army singers. In this context the prominence accorded to the “Battle Hymn” seemed like a vindication of the Bush administration’s military engagements and of America’s millennial mission more generally, much to the disappointment of those who opposed the president’s foreign policy or the conflation of worldly triumphs and spiritual redemption.

The election of Barack Obama in 2008 intensified the power of the “Battle Hymn” to polarize. The results galvanized the political Right, amplifying their fears that the traditional order was being dismantled before their eyes by a host of liberal enemies. Unsurprisingly the song quickly became a favorite at Tea Party rallies. Yet at the same time, Obama’s election also vindicated the millennial tradition of the black church, and the “Battle Hymn” was called upon to express the hope of many Americans that a sort of political millennium had in fact arrived. Progressives, many of whom had long felt marginalized from mainstream political culture, now felt the weight of their alienation removed. They were suddenly free to embrace American civil religion. In an article on the resurgence of “progressive patriotism” following Obama’s election, one historian recalled being overwhelmed with the impulse to hear the “Battle Hymn” in church.

The rival political interpretations of the hymn were on display in a controversy surrounding a group of New Jersey elementary school students who performed a song, to the tune of the “Battle Hymn,” celebrating Obama’s election at a Black History Month assembly. (“Hello, Mr. President we honor you today! / For all your great accomplishments, we all do say hooray!”) A video of the assembly leaked to the press, and conservatives pounced on the performance as an example of “political indoctrination.” Activists picketed the school, singing the original “Battle Hymn” while they marched. On his popular show, the right-wing television host Glenn Beck used the controversy to issue a contemporary jeremiad. After showing a video of a sixteen-year-old boy beaten to death when he was caught in a melee between two Chicago gangs, Beck asked his viewers, “What has happened to us? How have we come to a place where the value on human life is so incredibly low?” The answer, he insisted, was because “God is no longer trusted in America.” He then called attention to the New Jersey adaptation of the “Battle Hymn” as an illustration of this failing, suggesting that political messianism had supplanted traditional religious belief. That act of grade school revisionism illustrated for Beck the moral declension at the heart of all jeremiads; there was something especially damning in the tampering with Howe’s lyrics, which Beck explained were his “favorite collection of words in any song.” He quoted the final verse with tears in his eyes.

Around the same time, a law student, aggravated by “the whole of this latest election process,” composed a “divorce settlement” between the Left and the Right that spread quickly among conservatives on the Internet. Conservatives would keep guns, capitalism, Wal-Mart, Wall Street, Bibles, and Judeo-Christian values, he suggested. Liberals would keep the ACLU, abortion clinics, Oprah, and illegal aliens. The Left would get “Kumbaya,” while the Right would retain the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

There was a certain irony in the student’s claiming the “Battle Hymn,” a song originally composed to celebrate the efforts of those who fought to keep the Union whole against those who would split it apart, on behalf of a national divorce along partisan lines. On the other hand, the proposed settlement laid bare tensions that have long coursed through the hymn. For in heralding America’s millennial promise and fostering national reconciliation, the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” has also celebrated the final, cataclysmic sifting of the righteous from the unrighteous. It contains visions both of perfect peace and of violent discord and underscores the kinship between the two. When we reach for one, we have often taken in the other. The “Battle Hymn” reminds us that our most powerful visions of the coming of the Lord are pierced by the gleaming of the terrible swift sword. It reminds us as well that beyond the wrath and the trampling and the sword, the glory endures.

Reprinted from “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” by John Stauffer and Benjamin Soskis with permission from Oxford University Press USA. Copyright © 2013 by John Stauffer and Benjamin Soskis.