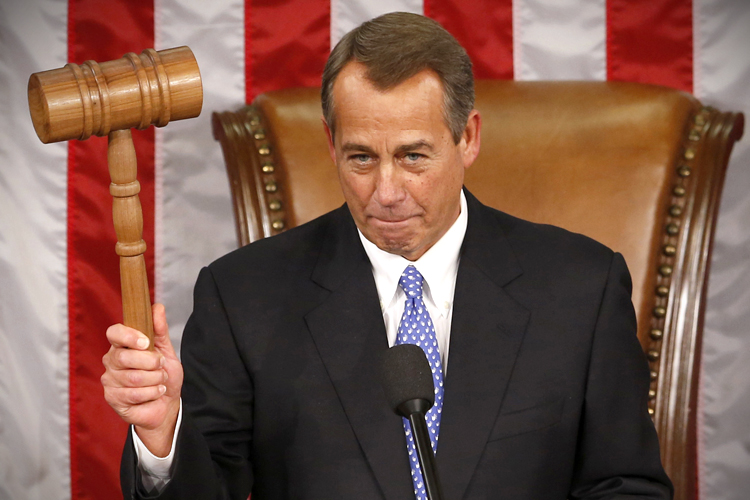

Some two years after John Boehner was first reported to be getting in trouble with the Republican conference – two years of constant reports that if this or that happens, he’ll be dumped as speaker and replaced with a “real” conservative – John Boehner is still speaker of the House of Representatives.

One never knows when a politician will get sick of it all and move on, but until that happens keep your money on more stories about Boehner’s speakership at risk, more stories of floor fiascoes such as the farm bill debacle this week – and more instances of Boehner surviving all of it.

Why? Because Boehner is actually doing his job well. It’s just that it’s an impossible job right now. The basic structure for why it’s impossible is well known. Boehner’s Republicans have a relatively slim majority; on any particular vote, it’s likely that either a group of moderates or a group of radical conservatives will want to dissent; and in a polarized House it’s unlikely that Democrats will furnish many votes without substantive concessions – and cutting deals with Democrats is almost impossible when Republican activists consider any compromise a betrayal. And, meanwhile, some bills simply have to be passed, meaning that 218 votes have to be found somehow. It all means that fiascoes such as the farm bill debacle this week are extremely likely.

Beyond that, it’s especially impossible for anyone to meet the standards that the Washington press corps expects.

In particular, the idea that a speaker should be able to “control” his conference just isn’t how things work in the House. Each Republican is, to a large degree, an autonomous politician who owes little or nothing to the speaker. It’s true that Republican members of the House do tend to be very responsive to the party, both in Washington and back home in their districts. But that’s true for the speaker, too. When the party is unified, none of them can really cross it.

Within that, however, there’s just not that many levers the speaker has to get rank-and-file members to do what he or she wants. And there are even fewer for Speaker Boehner, given the post-policy Republican Party.

- As some have noted, the demise of earmarks takes one tool away from the House leadership. One can make too much of this (there are plenty of ways to steer benefits to specific districts without earmarks), but it’s at least a small hit.

- Many Tea Partyers and other new members (and Boehner has an enormous number of short-timers in his conference) may not think of themselves as having long House careers, and therefore may not care all that much about committee assignments and subcommittee and committee chair positions.

- That’s doubly true in a party that just doesn’t have much of an agenda. Who cares if you’re on a key committee if there’s no legislation to move?

- Even worse: To the extent there’s an agenda, it’s more symbolic than substantive (see “border security” on immigration; experts believe the biggest problem is people overstaying their visas, but conservatives love the idea of a wall). But symbolism by its nature is a lot harder to cut deals on than substance.

- And on top of all that are two Tea Party themes that make it harder for the speaker: the knee-jerk “principled” opposition to compromise, and the obsession with “insiders” and “outsiders.” Basically, a lot of Republican members believe they can get in trouble with the Republican activists who got them there any time they look as if they cut a deal with the speaker, even if it achieves policy goals that those activists say they want.

That doesn’t mean a speaker is utterly without influence. After all, most of these limitations are partial, not absolute – even post-policy members who believe they’re only in Congress for a couple of terms may still care at least a little about committee assignments, for example.

What it does mean, however, is that the dysfunctional House is structural, not personal. And that means that if Boehner were bounced whoever replaced him would have exactly the same set of problems, whether it was Majority Leader Eric Cantor or anyone else. Even a rebel conservative would, simply by virtue of becoming speaker, suddenly become the dreaded “establishment” that Tea Partyers are looking for to rebel against.

Indeed, under these conditions – which should at least persist as long as divided government persists – Cantor or anyone else would be nuts to accept the job. So even though it’s in Cantor’s interest to cultivate a reputation as the real conservative alternative to Boehner, it’s also in his interest to keep the current speaker in office.

What might break the logjam could be a Republican landslide, which would suddenly make it possible to enact very conservative legislation into law. It’s also possible that over time, Members elected in the Tea Party waves who stick around may wind up wanting to build careers in the House – and thus have requests of the party leadership that could lead to more going along to get along.

But all that is in the distant future at this point. Until then, John Boehner is doing a solid job in impossible circumstances. I don’t think he’s going anywhere.