If P.J. O’Rourke was in fact dedicated to returning the National Lampoon to solid Middle American (as opposed to snotty Ivy League) values, he found a strong ally in John Hughes, a Lampoon writer so rooted in Middle America he never actually left his base in the Chicago suburbs even after he was put on the Lampoon staff, instead flying in for meetings at the magazine’s expense.

Like Alan Zweibel and Lorne Michaels, Hughes had slogged as a gag writer in his youth, selling jokes to the likes of Rodney Dangerfield, Joan Rivers and Phyllis Diller. Like Chris Miller, he had been a copywriter and became an agency vice president by the time he was twenty-five while freelancing for Playboy. In fact, it was Miller’s work that had inspired Hughes to contact the Lampoon. “I read all of Chris Miller’s stuff and a couple of things by Doug Kenney and the stuff drove me insane,” he recalled, and in late 1977, he called and ended up talking to cartoonist Shary Flenniken, who told him to get in touch with Tony Hendra, at that point incubating his own satire magazine. But the socialist-leaning, literary Hendra and the basically apolitical-though-Republican-if-anything Hughes (who would make his name in 1985 as writer and director of “The Breakfast Club,” a movie in which five high school kids are confined to a library and generally avoid reading, bored stiff though they are) were not a good fit.

O’Rourke and Hughes, however, were another story. “He became real tight with P. J. They were both proud Americans, for a strong defense, that kind of thing,” as Flenniken said, and soon Hughes was installed as trusted lieutenant and heir apparent. Lampoon editor and writer Ellis Weiner recalled that at the big brainstorming retreat, “at one point P. J. said, ‘We’re not going to do parody ads because people get confused and they don’t know what’s real and what isn’t,’ and John Hughes said, ‘Yeah, I agree with that. Let’s stop fooling people.’ It’s one thing to be at the New York Times or Time and say ass-kissing things to ingratiate yourself to power,” Weiner declared, “but the Lampoon should be—and used to be—the place where its whole existence was to see through that shit.” In fact, the Lampoon did keep doing parody ads but shifted the target from the ostensible corporate sponsors. Ted Mann’s 1978 “Senior Vittles” ad, for instance, mocked hard-up senior citizens’ apparently amusing inclination to eat pet food.

Hughes did not turn out to be unquestioningly supportive. He took a dim view of his editor’s aspirations to join the gentry, providing satirical reenactments of the fashionable Hamptons dinner parties O’Rourke dragged him along to. As well, Hughes may have been a Republican but he was hardly a Reptile. Instead, he was a self-described “really heavy homebody” who got married at twenty and had “not been on a date as an adult, not even close.” Moreover, he thought it was “real dangerous to be hip and try to write funny stuff, for me anyway. I don’t want to be too cool,” he said in 1985.

Hughes was clearly the ideal person to collaborate with O’Rourke on the Lampoon’s next special project, a follow-up to the High School Yearbook. This was the February 1978 Dacron (Ohio) Republican-Democrat, a parody of a small-town Sunday newspaper, the town being the home of the Yearbook’s Kefauver High. As the Lampoon proved so often, familiarity breeds the best satire, and the two Midwesterners were able to mock Middle American values without condescending to them, a trick another group of Midwesterners would later pull off even more spectacularly with the ongoing small-town newspaper parody The Onion.

The big headline of the Republican-Democrat refers to yet another attack by a notorious local criminal, the Powder Room Prowler, a menace still at large after several months despite his trademark high heels and bag over his head. This local story is given far more attention than such minor (and faraway) events like “30,000 Feared Dead in India” and “Japan Destroyed” (which receives a bit more play because the tragedy “has marred the vacation plans of Miss Frances Bundle and her mother, Olive”).

The true flavor of Dacronian life is conveyed in the ads for eateries like the White Curtain Inn, known for its “Time-Saver One Dish Breakfast,” a ham, cheese, and coffee omelet. Meanwhile, an advertising supplement created by non-Midwesterner McCall for Swillmart, “where Quality is A Slogan,” promotes goods like perpetual lunch meat, Snak Paste (“liver, peanut butter, mayo, lard, cheese—all in one E-Z squeeze tube”), and a digital grandfather clock.

Like the Yearbook, the Sunday Newspaper Parody succeeds in creating its own universe through an accumulation of interrelated detail. The society page brings us up to date on what has become of some of the Yearbook’s Kefauverites. Rich kid Woolworth Van Husen III is, unsurprisingly, in the family trailer business, while artistic Forrest Swisher is director of the “Dinner Theater in the Dell.” Elsewhere we learn that lone African-American student Madison Avenue Jones is a city councilman, class clown Herb Weisenheimer is now proprietor of “Hollerin’ Herb’s Psychopathic Chevrolet and Lunatic Used Cars,” and former beatnik and Dickinson grad Faun Rosenberg heads up a conservation group that is trying to stop hunters from shooting the wildlife that flocks to the warm (160 degrees centigrade) waters of the Lake Muskingum nuclear cooling pond. Meanwhile, Everystudent Larry Kroger, now a Kefauver High guidance counselor, has attempted suicide by jumping from the second story of his parents’ home.

However, when Dacron’s Malcolm X Lounge offers “Free Coke and V.O. to every white girl,” the Black Slant on the News column reports on a “Minority Math Course,” which accents “relevant arithmetical concepts” like odds and numbers, and every classified ad for questionable legal services (“Sue the @$’& Jerk! Let’s Go to Court!”) is placed by either Meyer “The Rabbi” Saperstein or David Goldstein or Krepstein, Shepstein, Weinstein, Feinstein, and Smith (not forgetting real-estate ads from local slumlord Swinestein), it’s not clear whether the writers are mocking small-mindedness or embodying it.

The Sunday Newspaper Parody was equal to the Yearbook and the Encyclopedia of Humor in its maniacal attention to detail. From the classifieds to the obituaries to the movie ads (all for fake movies except “Animal House,” which is acclaimed as being “much like American Graffiti,” “really a lot like American Graffiti,” and “so much like American Graffiti I understand there are a bunch of lawsuits being brought”), no opportunity for a joke or an appropriate typeface has been overlooked. “P. J. is a perfectionist,” Mogel said, “and every one-inch classified had to be funny.” Now he admires such zeal, but at the time, he “was screaming, ‘Why are we spending so much money?’ ” Fortunately, the newspaper parody became the Lampoon’s second biggest-selling special issue and served notice that O’Rourke was in charge.

It also smoothed Hughes’s path considerably, sparing him the worst of the still-harrowing initiation rites, which O’Rourke found himself “perpetuating in spite of myself.” This was attested to by a former Harvard Lampoon editor hired in 1979, the first ’Poonie to join the National Lampoon staff since the original group. “Here I was, the new kid; they’re supposed to teach me and take me under their wing but instead,” he recalled, “it was like having a Gila monster as an arterial clamp during open-heart surgery.”

At first, Hughes tried to come up with Milleresque pieces such as his April 1979 “My Vagina,” his own version of the transformed-into-a-woman story. With a keen sense that biology is destiny, the hero moans, “Next thing I knew I would be down in the basement doing a load of laundry with Mom!” In contrast to Kenney’s essential sympathy for his date-raped heroine, when Hughes’s protagonist is gang-raped, her main concern is that she will have to “use up most of my money I was saving for new skis . . . having to get an abortion.”

This kind of raunch was not really Hughes’s forte. In September 1979, he found his true subject with an article called “Vacation ’58,” a memoir of a family trip as seen through the eyes of a twelve-year-old boy. Four years later, this story would provide the basis for “Vacation,” written by Hughes, directed by Ramis, and the second hit movie from the Lampoon stable. While the magazine story is set in the ’50s, the film takes place in the ’80s, and the only way it can convincingly establish this very retro family structure of Chief Dad, Vice Chair Mom, and the Kids—all on a cross-country road trip—is by depicting it with a knowing irony. Just as the Reptiles could not embrace the Colonel Teddy Jingo attitudes of the past without a certain defensive self-consciousness, so these traditional gender roles could not be presented straightforwardly.

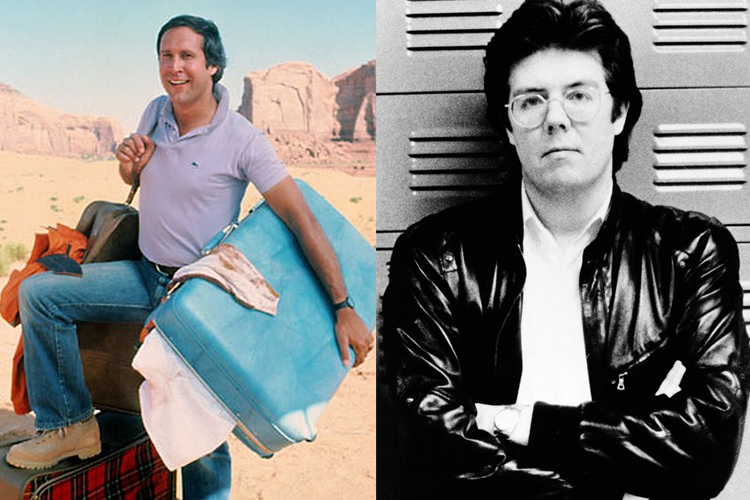

Casting Chase as would-be patriarch Clark Griswold ensured that any paternal authority was undercut by borderline buffoonery. In the original story, Dad’s authority is never questioned, even though all of his decisions turn out to be disastrous. In fact, the more he becomes a Bluto-like instigator of destruction and anarchy, the more his son respects him. For example, when Dad orders his son to throw an ice chest onto the road to slow down an approaching cop car, the boy exclaims, “This is so cool!”

In the film version, Dad is merely a bumbling incompetent. Any moral authority is vested in the kids, who appear to be the only calm and intelligent people present, humoring their parents’ simple enthusiasms. So while Clark is happily singing the theme song of Walley World, the Disneyland equivalent that is their ultimate destination, his son is rocking out to the Ramones on his Walkman. Even Clark’s role as sole breadwinner is undermined by the fact that he works in a totally superfluous and possibly harmful industry, food additives.

It’s as if Mom and Dad Griswold have come through the ’60s with their squareness untouched. “Clark Griswold is not a real person by a long shot,” Chase observed. “It’s a burlesque, and it’s very broad, so I could clown and mug more. I loved it.” One reason the role may have showcased Chase’s talents was because he had a large hand in writing it. “At first, I was supervising John Hughes’s rewrites,” Ramis recalled, “then Chevy and I took over when we thought he’d gone as far as he was going to go.” As for how Hughes felt about having his baby taken away from him, “I think John was happy to get the movie made and that it was successful,” Ramis hypothesized, saying it was only later that Hughes “learned to resent it.”

In presenting the middle-aged Clark as already on the verge of senility and vastly less able to cope than his composed son, Hughes was starting as he meant to go on. Much of his work for the magazine, not to mention his subsequent screenplays, is pervaded with the feeling that once you’re over eighteen, you’re past it, a notion that was naturally flattering to a teenage audience. For example, his August 1978 Real Teen Magazine, another parody of the kind of publication that inspired Poonbeat, gives ample evidence of his ability to view life from the teen perspective. A special report that asks, “Is it okay to kill your parents?” attracts responses such as “The best,” “Except for detention it was a good idea,” and “I should have done it a long time ago before they used up all the money sending my brothers and my sister to college.”

Other articles offer hints on “Breaking Up Your Parents’ Marriage,” “Household Drugs,” and, for girls, “Pretend Rape—Using It to Get What You Want from Older Men” (this accompanied by a photo of a guilty-looking Lampoon publisher Marty Simmons passing money to a young girl). “Whenever I have a man teacher in school,” our correspondent reports, “. . . I just tell him on the first day that if he doesn’t do what I want, I’ll tell my parents he fucked me”—certainly one explanation for why teenage girls were starting to outperform boys academically.

Although O’Rourke made it clear that he viewed Hughes as his successor, his Republican-Democrat collaborator had other plans. Even when, with a family to support, Hughes finally gave up his advertising job in 1979 for the more chancy life of a Lampoon editor, it was only as a means to an end. “Turning 29 was really tough for me,” he said. “I thought ‘if I don’t move now then I’m too old.’ I didn’t want to be on my deathbed thinking I should have written a movie.” Having achieved this goal, he was already aiming higher. During the making of “Vacation,” Ramis recalled, “John was already telling me the idea for ‘The Breakfast Club,’ so he was definitely planning to direct even then, and I’m sure the offers were already out there.”

Five years later, thanks to “The Breakfast Club’s” huge success, Hughes would not only be directing but would have total creative control of his films, which ultimately became generational touchstones for ’80s teens. But first, he had to languish in what Mount called “some kind of indentured servitude” to Simmons.

Excerpted from “That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick: The National Lampoon and the Comedy Insurgents Who Captured the Mainstream” by Ellin Stein. Copyright © 2013 by Ellin Stein. With the permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.