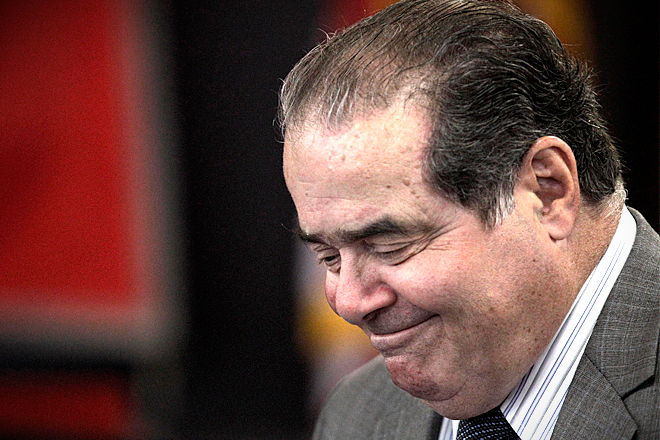

Recent events in Washington invite us to think about the meaning of democracy. On June 19, dignitaries gathered in the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center to unveil a statue of the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who was rightly described by New York Sen. Charles Schumer as a man who “dedicated his life to freedom, justice, and democracy.” On June 30, the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in United States v. Windsor, a case in which the Court held Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act violated the United States Constitution. In his dissenting opinion in the case, Justice Antonin Scalia accused the majority of nothing less than an assault on democracy.

There is much to be said about Scalia’s dissent, but in what follows I’d like to focus on what I take to be the political philosophy – more specifically, the conception of democracy – at the foundation of his opinion and show why I think this conception fails to live up to what Douglass called “true” or “genuine” democracy.

The political philosophy at the core of Scalia’s dissent is majoritarianism. The “beauty of what our Framers gave us,” he wrote in Windsor, is “a system of government that permits us to rule ourselves.” The Court could have chosen the path of “honor,” Scalia argued, “by promising all sides of [the same-sex marriage] debate that it was theirs to settle and that we would respect the resolution. We might have let the People decide.” According to Scalia, the Court’s cardinal sin in Windsor was to step in and interfere with the will of the majority.

If Scalia is right to say that majoritarianism is the heart and soul of the American Constitution, then it is easy to accept his claim that the Court committed a great crime against democracy in Windsor. But we need not reach this unhappy conclusion. The American constitutional tradition contains within it an alternative conception of democracy – we can call it liberal democracy for short – and there were few more eloquent defenders of this conception than Frederick Douglass.

In his fights against slavery and for equal rights, Douglass thought deeply about the meaning of democracy. In his speeches and essays, he attempted to distinguish his own views from the ideas of false prophets of democracy like Illinois Sen. Stephen A. Douglas, who championed the majoritarianism favored by Justice Scalia. Sen. Douglas’ understanding of democracy, the great abolitionist declared, is nothing more than a democratic version of might makes right. “By a peculiar use of words,” Douglass wrote in 1860, “[Senator Douglas] confounds power with right … By his notion of human rights, everything depends upon the majority.”

According to Douglass, majoritarian democracy lacks a sound “philosophical theory” at its foundation. It is not “genuine” in the sense that it lacks any justification for itself beyond power. The fundamental flaw in the majoritarian conception of democracy, Douglass wrote, was that it violated “the only intelligible principle” on which democracy can be based: the equal dignity of each human being. “The right of each man to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” he concluded, “is the basis for all social and political right.”

It is precisely this vital element that is missing from Justice Scalia’s understanding of democracy. While the right to govern ourselves collectively is part of the “the beauty of what our Framers gave us,” it is not the whole of it. This right exists alongside the rights of individuals to be treated with dignity and respect.

In his Windsor dissent Scalia all but mocks the majority’s concern for the “personhood and dignity” of individuals and contends that not only should the government be free to exclude same-sex couples from the institution of marriage, but he reminds us repeatedly that he believes the government should be empowered – if the majority wills it – to imprison homosexuals for making love in the privacy of their own homes.

What one cannot detect in Scalia’s Windsor dissent is an appreciation for the idea that true democracy entails not only collective self-government, but respect for the right of the individual to govern his own conduct. Scalia’s dissent has all the markings of a brand of democracy too shallow to accept. Genuine democracy – like the conception of democracy defended by Frederick Douglass – is far more worthy of celebration this Fourth of July weekend.