Why has Marco Rubio taken the lead on both immigration and, soon, abortion? Odds are you know the answer to that: He’s running for president, and he wants to position himself on the issues. What you might not realize, however, is how important presidential politics is to how the Senate works.

For example, contrast what Rubio’s been up to with Republican members of the House, who often seem to have lost any interest in policy. Now, many politicians are just inherently driven to make policy; that’s why they wanted the career in the first place. But it’s hard to see where the rewards are for members of the House to become policy innovators.

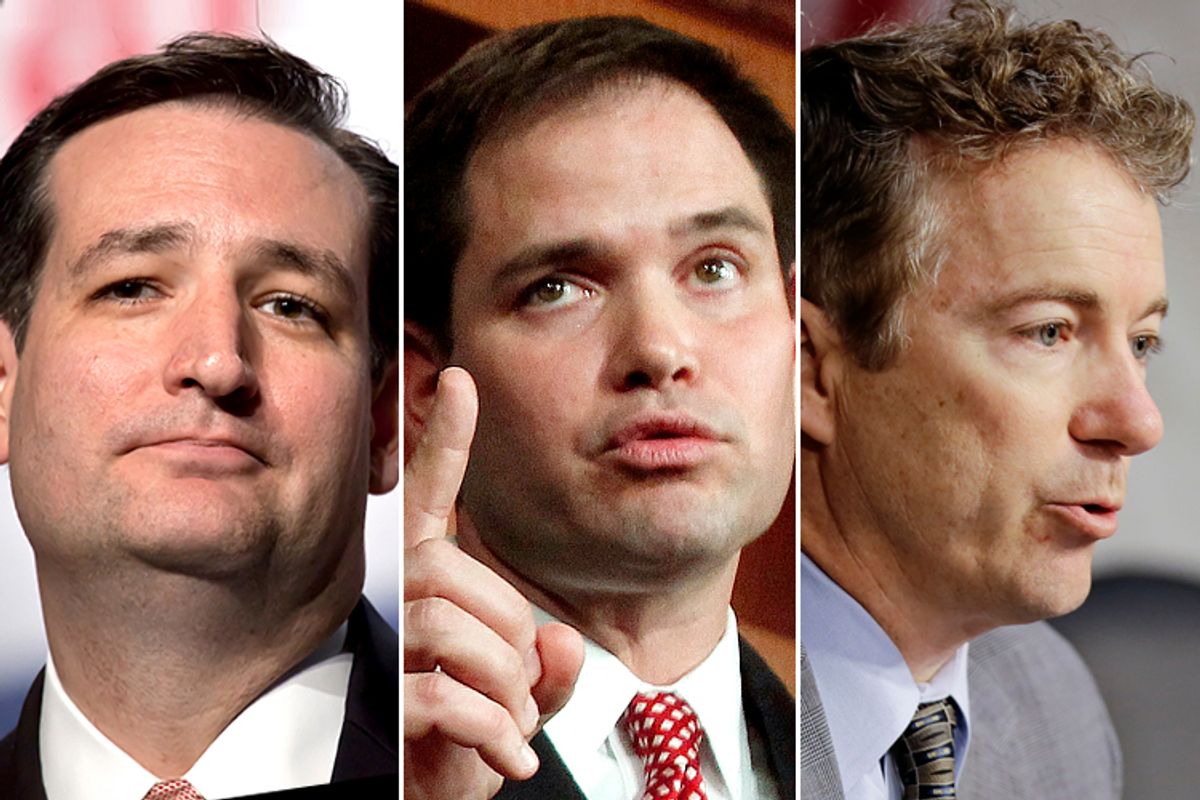

Not so in the Senate. And it’s not just Rubio. Just on the Republican side, there’s Rand Paul’s filibuster and other leadership on privacy issues, and while it was more symbolic than substantive, one might count Ted Cruz’s agitation against confirming Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel. All three of them are at some stage of running for the White House.

In fact, as the political scientist Nelson W. Polsby used to argue, much of the way the Senate works can be seen in terms of the number of senators who act with at least one eye on the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue. It’s a well-known cliché that when senators look in the mirror, they see a president – and it’s a cliché well-rooted in fact. I counted at least 28 senators from the 99th Senate (1985-1986) who at some point either actively ran for the presidency, were vice-presidential nominees, or who came close to a White House run. If we add V.P. short-listers, my count for the 104th Senate (1995-1996) reaches 31 national candidates or almost-candidates.

And who knows how many of the others are thinking presidency, even if to outsiders it might seem preposterous. In the 109th Senate (2005-2006), I count only 16 who have run for the presidency so far. But that doesn’t count Bill Frist, Jay Rockefeller, John Thune and Jim DeMint, all of whom surely thought in terms of national constituencies at least for a while (and that group may yet produce a candidate). It doesn’t count Dianne Feinstein and Jon Kyl, both of whom have been rumored finalists for a V.P. selection – as was, long ago, Daniel Inouye. And it doesn’t count all those senators who thought they were on that path, only to be derailed by early defeat or scandal or some other distraction.

What all of that means is that senators, who already have larger and more diverse constituencies than members of the House, have yet another reason to think in terms of national issues, rather than simply catering to narrow groups in their states. It also gives them a strong incentive to attract national press attention, in order to build national constituencies.

Think, for example, of Oregon Sen. Jeff Merkley, who has been a leader on filibuster reform. I’ve never heard whispers about Merkley making a future presidential run, but I suspect it’s crossed his mind – because he’s one of 100 senators, and every time he goes to the Senate floor he sees John McCain and Tom Harkin and Lamar Alexander, and he also sees rumored current or future candidates such as Rubio, Paul, Cruz, Elizabeth Warren, Amy Klobuchar, Mark Warner and Kristen Gillibrand. It must be hard to look around and not think: Why not me? Especially since we’re talking, to begin with, about people who were able at one point in their lives to look in the mirror and see a United States senator well before they made it a reality.

Now, it’s possible that Merkley would care about the filibuster even if the presidency never crossed his mind. The same is true for Rubio and immigration, Paul and drones, or Cruz and whatever he’s been up to lately. But the possibility of a presidential nomination certainly creates incentives for them to take the lead on issues that could appeal to a national constituency – and if a few dozen senators are always doing that, then they also are providing an example for the rest of the body.

All of this has been true for some time (Polsby dates it back to the 1950s at least). It’s almost certainly received a bit of a boost recently because senators have been quite successful of late. Barack Obama was the first to go directly from the Senate to the White House since John F. Kennedy in 1960, and senators also won nominations in 1996 (Dole), 2004 (Kerry) and 2008 (McCain along with Obama).

The bottom line? There are a number of factors in the U.S. system of government pushing toward local, fragmented concerns. The electoral ambitions of senators turn out to be a major factor pushing toward national ideas – and it provides incentives strong enough that it appears to be overcoming the Republican Party’s strong aversion to doing public policy.

Shares