Chuck Klosterman has a theory about “Star Wars,” which to anyone familiar with his work will probably qualify as the least surprising statement ever made. Klosterman is a pop culture critic, so having theories about “Star Wars” is virtually his job description. This particular theory goes like this: For the youngest male fans of the films, the series’ most beloved character is Luke. Once they get older, they come to prefer Han Solo. In true adulthood, however, “you inevitably find yourself relating to Darth Vader. As an adult, Vader is easily the most intriguing character and seemingly the only essential one.”

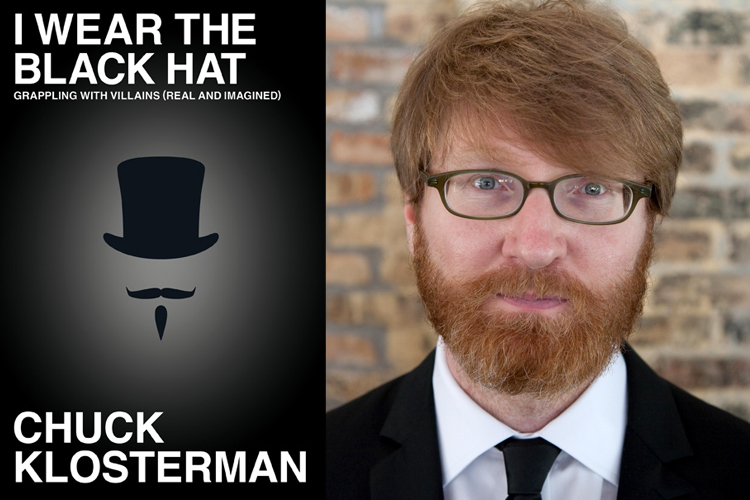

Not being a male “Star Wars” fan, I can’t testify to the accuracy of this theory, but it has a pleasing quality. It’s got the tripartite format of folklore and it even constitutes a compressed, skeletal narrative, right down to the twist at the end, that tang of contrarianism so essential if you want to be interesting on a subject people have already over-discussed. I can’t honestly call myself a Klosterman fan, either, although I did very much enjoy “I Wear the Black Hat: Grappling With Villains (Real and Imagined),” his new collection of linked essays. I’ve never read anything else by him, apart from the occasional journalism, mostly because I’ve understood him to write primarily about pop music and sports. These are subjects in which I have not only no interest, but also insufficient knowledge with which to assess such observations as, “They put way too much effort into acting like they were pretending to work hard at casual brilliance” — made about a band called the Yeah Yeah Yeahs.

A good chunk (though far from all) of “I Wear the Black Hat” is indeed about sports, and there is an entire chapter titled “Another Thing That Interests Me About the Eagles is That I [Am Contractually Obligated to] Hate Them,” in which Klosterman lists all the musical artists he has hated in chronological order of the years during which he has felt it necessary to hate them. But that essay is primarily about what Klosterman has come to regard as the arbitrariness of his hatred and about the moment when he realized he could not sustain it. In 2003, he suddenly knew that he could no longer go on hating the Eagles — another position that had previously approached the status of a job requirement for the likes of him. “I didn’t love them, but I certainly didn’t view their subsistence as problematic or false or socially sinister. … I no longer possessed the capacity to hate rock bands.”

This revelation was vertiginous, because attaching great significance to matters of taste is what rock critics do. In a byzantine account of the switchbacking reputation of Taylor Swift included in the same essay, Klosterman conveys the absurdity of the rock-critical enterprise, in which capricious style choices and public-relations moves are scrutinized for their compliance with a chimerical standard of authenticity. Recognizing this absurdity precipitated a crisis because caring about such matters was once, apparently, the organizing principle of Klosterman’s worldview. If the Eagles are not actually morally wrong, as he had always assumed, then which of his other beliefs might also be built not on bedrock, but on sand?

The possibility that all understandings of good and evil are essentially arbitrary, merely the result of values absorbed from our environment, causes Klosterman, in the book’s first essay, to ping around a bit between Nietzschean and Althusserian ideas and to briefly review the famous “veil of ignorance” thought experiment of philosopher John Rawls. (The latter asks the thinker to imagine the society you would want to live in with the provision that your position in that society cannot be determined in advance. What world would you want to wake up in if you had no foreknowledge of who you’d be — rich, poor, male, female, black, white, etc. — when you woke?) People don’t want to apply the same experiment to morality, Klosterman argues, because we don’t want to believe that good and evil (rather than justice) are “things we decide.” We want to believe that morality is innate, or, as Klosterman puts it, “decided by someone else.” (Actually, those two things are not equivalent, but the possibility of a biological foundation of morality is not something he considers.)

This sounds pretty heavy, but the rest of “I Wear the Black Hat” is about Batman and Prince and O.J. Simpson and Perez Hilton, rather than Immanuel Kant. It’s about how we judge right and wrong in the puppet theater of the mass media, as it is acted out not by human beings but by personae, figures of limited dimensionality who are managed (though often not very well) by human beings. This is not trivial stuff, because most Americans do not spend much time thinking about morality in the abstract. Instead, the moral thought experiments we devote the most mental energy to are questions like: What — exactly and if at all — did Bill Clinton do in the Monica Lewinsky scandal that was morally wrong, as opposed to merely foolish or arrogant? Is Muhammad Ali a “good person” despite the inexcusable way he treated Joe Frazier? How can Joe Paterno’s grievous moral failure in the Jerry Sandusky affair be balanced against the good he did as one of “the two or three greatest college football coaches of the 20th century”?

“I Wear the Black Hat” is also about how we determine who is a “villain,” which is not entirely the same thing as deciding who’s in the wrong. The bad guy, or antagonist, is a creature of storytelling rather than an element of everyday moral life. But it is ever more a feature of the mass media that our villains and heroes are adapted from actual events and real people, people who are remade in the public imagination as players in an ongoing tale. We often can’t tell the difference. I know two people who have, in the course of our acquaintance, become famous enough to acquire a public image that seems somehow independent of who I feel they really are. Each one’s behavior has certainly contributed to that image, but just as much of the image is made up of preexisting stereotypes (home-wrecker, highbrow snob, snotty artist) embedded in the average person’s mind and cannily triggered by press reports. All the time I encounter people who have never met my two friends and yet are absolutely (and erroneously) convinced they know just what they’re like.

These images, these personae — not art but not entirely fact, either — are the real subject of “I Wear the Black Hat.” Klosterman has a theory (of course!) about how someone becomes a villain in the theater of personae, which goes “In any situation, the villain is the person who knows the most but cares the least.” He applies this formula to various examples: Machiavelli, who despite having done nothing reproachable, has become the eponym for calculating, cold-blooded villainy; technocrats like Kim Dotcom, founder of Megaupload, who use their superior command of technology to impose social change on others whether they agree to it or not; Sharon Stone’s character in “Basic Instinct,” who is clearly the bad guy in the film whether or not she is guilty of the murder Michael Douglas investigates. But even Klosterman is forced to admit that this knows-most/cares-least formula is not universally applicable; it doesn’t, for example, capture Adolf Hitler, who has become the personification of evil in Western culture.

No matter: The value of arguments like Klosterman’s lies less in their ironclad validity than in the pleasure to be found in kicking them around. How did vigilante Bernhard Goetz go from popular hero (in the first few days after he shot four teenagers attempting to mug him on a New York subway train) to widely acknowledged disturbing weirdo once he began speaking with the press? “Goetz talked too much,” Klosterman posits. “He tried to own his own persona, and that made everything worse, as it always does.” Keeping your mouth shut is, Klosterman feels, usually the best policy because it allows the public to make of you what it will; the flatter and blanker you are, the more useful you become as a screen on which to project our fantasies. When no one knew anything about Goetz, he was almost fictional, like Batman, a heroic vigilante we’d regard as a scary maniac if he appeared in the real world.

On the quip level, Klosterman hits more than he misses. “Basic Instinct” really is “better to remember than to rewatch.” The line between low- and high-end television really is described by how drug dealers are depicted (2-D baddies = low-end; complicated-to-sympathetic = high-end). It is true that “for his art to succeed, Lars von Trier needs to be despised by the reactionary segment of his liberal audience. His movies aim to confront people with ideas they will never truly accept.” And even when you can’t tell whether he’s right or not, Klosterman is always interesting. I have no idea if Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was widely considered “not likable” because I barely know who he is, but I’m still fascinated by the idea that this unlikability rose from his refusal to “ignore the stupidity” of the “false relationship” between sports figure and fan.

One person Klosterman explained his “Star Wars” theory to (the editor of this very book, in fact) suggested that the author wanted to write “I Wear the Black Hat” because “you’re afraid that you are actually a villainous person.” This seems confirmed by the book’s preface, in which Klosterman describes looking out his window and fretting, with David-Foster-Wallacean contortions of self-consciousness, over how little he feels for the people he sees outside. He knows too much, and doesn’t care at all. He feels particularly bad about a jerky kid he met in eighth-grade basketball camp and thereafter regarded as his archenemy, going so far as to describe the guy as such in an Esquire column. Later, he learned that the man, a professional athlete named Rick Helling, became “the first baseball player on record for taking a public stand against anabolic steroids,” and continued to speak out about the issue until the world caught up to him.

Yet Klosterman admits that he pettily refuses to assimilate the fact that Helling is probably, on balance, a good guy. It suits him to go on seeing Helling as bad because Helling once behaved badly toward Klosterman. The mold was set long ago, and even though Klosterman now knows better, “I just don’t care.” Therefore, “In my own story, I am the villain.”

But what would Helling say? Probably that he, too, doesn’t care, because whatever Klosterman has said against Helling, it was just talk, and fairly silly talk, too, as Klosterman himself acknowledges. Villainy may have its foundation in knowing a lot and caring a little, but it’s only truly bad in the doing, beyond the theater of the personae, where the boundaries of our limited selves collide and good and evil become something more than theoretical. Klosterman has wronged Helling only in his own mind — admittedly a pretty interesting place, but far from the only game in town. If we could ask Helling about it, he’d probably just laugh and say, “Chuck, you need to get out more.”