“Motherfucker,” said Lee Daniels as he lay, completely horizontal, on a sofa in his room in New York’s Waldorf-Astoria. “That’s how I want to start. What the fuck?”

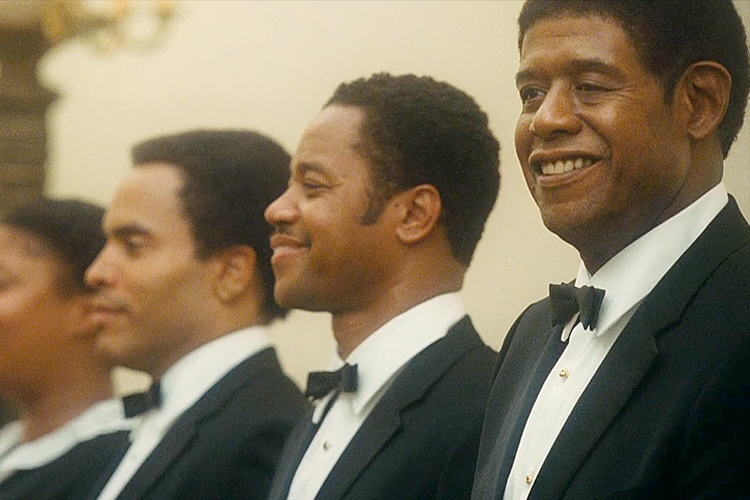

Daniels, who rose to prominence in 2009 with his film “Precious,” was promoting his latest film, “Lee Daniels’ The Butler,” a film adapted from the life story of Eugene Allen, a black man who served eight presidents and lived to see the election of Barack Obama. (In the film, he’s called Cecil Gaines and played by Oscar-winner Forest Whitaker.) But though the film ends in November 2008 and on a sunny and optimistic note, Daniels observed that recent developments showed that America has a long way to go on race issues. “They trick you,” Daniels said. “They put Obama in office with all this messiness underneath.”

“When we made this film, Trayvon Martin hadn’t happened,” said Daniels. He also noted that Lyndon Johnson’s passage of the Voting Rights Act was a major set piece in the film — and that now, that legislation has been overturned. “It was snatched! They’re saying now, that if my grandmother don’t show ID at the polls, she can’t …” He trailed off. “I can’t believe I’m having this conversation.”

“In 2013,” he said, comparing the killing of Trayvon Martin to an early “Butler” scene in which Cecil’s father is killed, “any white man can kill a black man and get away with it. That’s crazy!”

“The Butler,” as it’s known (the “Lee Daniels” credit in the title is the result of a bizarre legal fight), depicts Cecil’s personal and professional life; at work, he’s a confidant and silent influence upon the president, while at home, his marriage suffers and one of his two sons becomes involved in militant activism. This is a broad and often messy movie — presidents from Eisenhower to Reagan are portrayed by famous actors with varying degrees of accuracy, and the butler’s sway over them and over U.S. policy seems at time overdrawn. And yet its depiction of a father-son relationship between a service-industry employee and a Black Panther, as well as the participation of many of the film industry’s most venerated black performers, gets at a question at least as old as W.E.B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington’s writing: Is it better to assimilate and attempt to change the system from within, or to rebel?

Resentment, said one of the film’s stars, is poisonous. “I’m 44 years old now,” said Terrence Howard, who appears in the film as Howard, a dissolute neighbor to the titular butler. “In my early 20s, I was extremely angry. I couldn’t help but see the glass half-empty and be constantly aware of what’s been stolen from me. What I didn’t have — if I was a white actor, I would have had this. All these what-ifs, which are mind-identifications with the past, which are mind-identifications with a future that doesn’t exist.”

Howard said that, thanks in part to the writings of Eckhart Tolle, he’d learned to move past racism. He wasn’t sure why people were upset over the acquittal of George Zimmerman: “I feel personally that we weren’t upset when O.J. got off. We never know what is the actual justice of the moment. At the end of the day, it’s the universe that will bring justice to what has to take place. And Trayvon Martin, the martyrdom that has occurred with his life — that spilled blood will give birth to many trees and powerful things of freedom in the future. And George Zimmerman, he himself may come out to become a better person. We have to be patient with our judicial system, and we have to be patient with our consciousness as people and know that down the line, everything will come to a balance.”

It’s not as easy for others to remain sanguine about the Zimmerman trial. Cuba Gooding Jr., who plays one of Cecil’s co-workers, said, “When I saw and heard that one juror saying she thought he was guilty it makes you want to pull your fucking hair out. I get how you got her to say that’s the law of the land. But you’re missing the big picture here!”

Even so, Gooding says, the situation has improved — not least because a black director and stars are able to make a movie about their experience. Referring to “The Butler,” “Fruitvale Station” and the upcoming “12 Years a Slave,” all directed by black men and about race in America, Gooding said, “These filmmakers got their rise because the greedy studios finally broke the system enough that all of the indie dramas that would’ve been done within studios with white leads and white directors now happen to be done with the best directors. Hopefully, eventually, we’ll get to work with real budgets, and not have to work for a hand-job and a bucket of chicken!”

“When I saw ‘The Color Purple,’ it blew me away,” he said. “But it was made by a white, Jewish director. That film today would be made for a fraction of the budget. And he just might have been a director of color.”

For his part, Daniels is accessing personal experience in “The Butler,” a story that, for all its commonalities to “Forrest Gump,” he insists is not meant to be an allegory for all of black experience. “Many [members] of my families are nannies,” he said, “and these white children trust them more than they trust their parents. They’ve grown up with these kids, they’ve confided in these kids. Since we’ve come up from slavery, white people have trusted us. Because we’ve been subservient.”

But subservience has its limits. And a quiet anger underpins both the movie — which shows the limits to which a butler can subvert white hegemonic rule — and Daniels’ life. “It’s politically incorrect to play the race card. And I try not to do it, because it’s in poor taste, because if I saw it, then it became real to me. If I really acknowledged people watched me when I went in stores, it’d become real to me. And I don’t think any white person would know what it’s like to go into a 7-Eleven and be followed. And to raise your hand and be ignored. It’s a slow, slow, slow, subliminal chipping at one’s spirit. Inevitably, there’s no way you can’t feel inferior. Period.” Daniels described getting pulled over and slammed against his Mercedes on the way to the 2002 Oscars, at which Halle Berry won an award for “Monster’s Ball,” a film he produced.

“It’s what happens that we choose to ignore that white Americans will never be able to understand. Ever. But you can sympathize.”

Whitaker, for his part, was hesitant to discuss his own recent experiences with having been stopped and frisked at a New York market earlier this year. But he saw it as an opportunity for incremental change: “I think it’s a reminder of how far we have to go,” he said of the incident. “There’s different ways to approach things. Sometimes you want to go to the core of problems and figure out the core. In this case you might want to activate a training program.”

Asked if the conversation around race would ever end, Whitaker, a father of four, was slightly more optimistic. “I hope one day we do. Maybe not in my lifetime, but damn, it’d be great if my kids wouldn’t have to.”

“My children know there’s social injustice going on in this country and around the world,” he continued. “They’re emotionally affected by the Trayvon Martin case; they know about Oscar Grant; they know about many other individuals. They look at that, they look at sexual profiling — people beaten to death for their sexual preferences. All of those things, they are aware of. The movie is trying to stay it’s still happening. It’s still getting better. Do we still need to work on it? Yeah. But we’re in a car driving to a destination.”