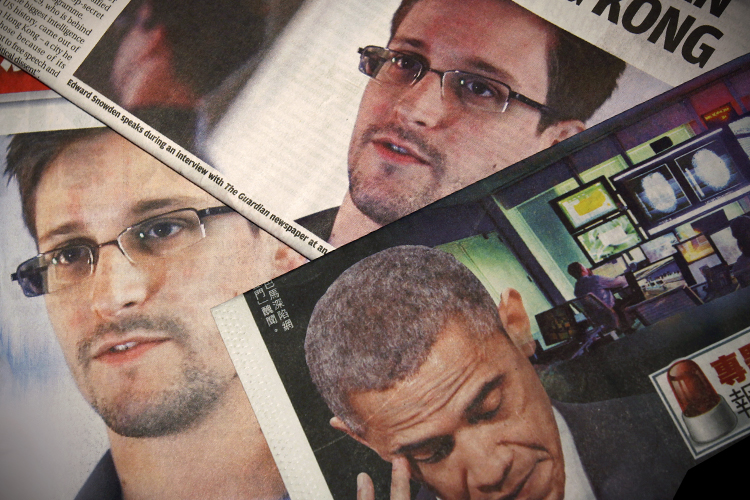

President Obama is no fan of Edward Snowden, as he made clear (again) at a White House press conference on Friday.

But what if by commenting extensively on the consequences of Snowden’s disclosures, Obama weakened his administration’s legal case against Snowden himself, should he someday face prosecution in the U.S.?

That could be the case, according to whistle-blower protection experts and attorneys I spoke to this week. First, defense attorneys could use Obama’s remarks to argue that Snowden had revealed information that was inappropriately classified. And though that argument would be unlikely to carry the day in court, Obama’s statements could plausibly secure Snowden a more lenient sentence, should he one day be convicted in a trial.

“You’re right to say that if the president concedes that the public should debate these surveillance programs, then he is admitting that the information about them should not have been classified in the first place,” said Bea Edwards, executive director for the Government Accountability Project. “In which case, prosecuting Snowden for releasing classified information improperly looks shaky.”

That would be an argument Snowden’s attorneys could make in a hypothetical trial, based on the most candid portion of Obama’s Friday remarks.

In criticizing Snowden, Obama acknowledged two inconvenient truths: that he himself had underestimated public anxiety about these collections programs, and thus that more information about them should be made public; and that Snowden’s disclosures had accelerated the public debate about U.S. surveillance capabilities and practices.

Specifically, Obama said:

[W]hat is clear is that whether, because of the instinctive bias of the intelligence community to keep everything very close — and probably what’s a fair criticism is my assumption that if we had checks and balances from the courts and Congress, that that traditional system of checks and balances would be enough to give people assurance that these programs were run probably — that assumption I think proved to be undermined by what happened after the leaks.

I think people have questions about this program. And so, as a consequence, I think it is important for us to go ahead and answer these questions. What I’m going to be pushing the IC to do is rather than have a trunk come out here and leg come out there and a tail come out there, let’s just put the whole elephant out there so people know exactly what they’re looking at … [T]here’s no doubt that Mr. Snowden’s leaks triggered a much more rapid and passionate response than would have been the case if I had simply appointed this review board to go through, and I had sat down with Congress and we had worked this thing through.

Defense counsel could use the first acknowledgment to argue for an acquittal, and could marshal both, should Snowden be convicted, to argue that he deserves a more lenient sentence.

“[A] legal channel that might be effective for Snowden would be to argue that the programs he disclosed should never have been classified in the first place, and if you took that approach, then the president’s statement about them might be helpful,” Edwards told Salon. “If the president himself is saying there’s a compelling public interest in the public having this information then the question arises why was this information classified to begin with. If the information were then properly classified or declassified then Snowden should not be indicted or penalized for releasing to the public information that should have been available to them anyway.”

That by no means suggests Snowden would easily beat the rap against him. Courts are generally extremely hesitant to question executive branch classification decisions, even when they stretch logic. It’s the exception, not the rule. Likewise, Snowden is charged with violating the Espionage Act, to which there’s no public interest exception — so the question of intent would be irrelevant.

Edwards and other lawyers and experts emphasized that Snowden will be legally trapped if he ever faces prosecution.

“Legally speaking, Snowden is not a whistleblower,” notes Mark Zaid, a Washington attorney who represents national security whistleblowers. “There are very specific criteria. He doesn’t meet any criteria because he didn’t follow the process.”

But even if he did, Zaid adds, “Whistleblower status has no impact on criminal culpability or liability, so the extent to which Snowden or anybody else could actually be considered a legitimate whistleblower — including to have followed the rules, which, of course, he didn’t do — from a legal standpoint it would have nothing to do with whether he’s guilty or not.”

For that reason and others, it’s a stretch to think Obama’s semi-exculpatory statements would matter in court.

“I don’t think the president gave away the case on Friday,” says Steve Aftergood, a secrecy expert and director of the Federation of American Scientists. “I think anything a defense attorney argued could be rebutted by a competent prosecutor…. A defense attorney would almost certainly argue that the information was improperly classified, but up to now that has never been a winning argument at trial.”

But Obama’s comments and other potential developments — if Congress were to change the relevant sections of the PATRIOT Act and FISA, say, or if the Supreme Court, in an unexpected turn, declares the collection programs Snowden disclosed to be unconstitutional — could could impact the case in different ways.

“If someone has developed an aura of whistlelower status, prosecutors might think twice about prosecuting, or consider reduced charges or a plea bargain,” Aftergood notes. “Another way it could affect the outcome is in how the jury comes to view the case. The jury is usually given instructions that they have to adhere to a certain view of the law, but they may consciously or unconsciously reach a conclusion shaped by a perception of whistleblower activity.”

(Zaid notes, as a caveat, that Snowden would still be on the hook for revealing information unrelated to the two collections programs at the center of the ongoing surveillance controversy.)

Trevor Timm is a legal expert and surveillance activist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and is skeptical that Obama’s comments would alter the course of a trial — in part because executive branch attorneys would likely contend that his comments should be inadmissible; in part because the question before the court wouldn’t turn on the value of the leaks; and in part because courts have been unfriendly to leakers.

“[T]hey would probably argue that the president’s statements are hearsay, since he wasn’t making them in court,” Timm says. “All they need to prove is that he had reason to believe the information may be harmful. The idea that his leaks have value doesn’t really ever — judges have generally disallowed that.”

Typically, Espionage Act indictments don’t result in full trials. “Judges rule on this stuff pre-trial and defendants usually plead out to avoid facing decades in jail,” Timm said.

And if he does, Timm is pessimistic. “All these avenues that one would think should be available to someone like Snowden, just through common sense, haven’t been available,” he said. “Because the sample size is so small, it’s possible that a judge would go in another direction, particularly given how high-profile the Snowden case is, but recent history suggests otherwise.”

But Timm, Edwards, Aftergood, and Zaid all agree that Snowden could marshal Obama’s comments to argue for leniency during a sentencing hearing.

“I do think there are things there that a defense counsel could use but it goes more to sentencing than to liability,” Zaid said.

“Perfect example is the Bradley Manning trial where the defense wasn’t allowed to say anything about his intent, or the fact that the government’s own assessments showed his leaks didn’t cause any significant damage during the trial,” Timm added. “But now this information is all coming out in the sentencing hearing.”