The revival of the feminist movement during the 1960s, and its growing influence over the following decades, moved the public conversation about rape from silence to exposure and political activism.” Second-wave feminists tried to put women’s experience of sexual violence at the center of a new political analysis of rape. Although they built upon many of the historical precedents set in the suffrage era, including the demand for women’s legal rights, the new generation of feminists in the later twentieth century launched a more radical critique that explicitly linked the problem of sexual violence to male privilege. As it evolved from the radical margins to the political mainstream, the movement proved far more effective than its predecessors in changing both laws and institutional practices. The rapidity of the shift, evidenced by an explosion in media coverage and legal reform, suggests that the spark of feminist politics ignited a backlog of fear and resentment among American women, many of whom had felt both physically at risk and politically disempowered by the threat of rape. Applying the radical feminist dictum “The personal is political,” writers and organizers reframed sexual violence not merely as a private trauma but also as a nexus of power relations and a public policy concern.

Both the black freedom movement and the sexual revolution fueled this new analysis of rape. In the postwar decades black women in the South had begun to press rape charges against white men and to politicize interracial rape as a civil rights issue. Young white women who cut their political teeth in southern voter registration and community organizing campaigns in the 1960s brought the concept of personal empowerment they learned there into the revived women’s movement. At the same time, the “sexual revolution” created both new opportunities and new dilemmas for white women. The decline of the purity ideal, the belief that sex was acceptable as an individual pleasure apart from any reproductive goals, and the availability of contraception all encouraged nonmarital sex. In the past, preserving chastity and preventing out-of-wedlock births had given them leverage in negotiating whether to consent to sex. In the new sexual order, the standard for consent had to be renegotiated. Why would a woman say no if sex presumably resulted in no harm? And who would believe that a woman had withheld consent, given new expectations of participation in the sexual revolution? Interracial relations created further dilemmas, as white women in the civil rights movement learned. While some chose to break the taboo on interracial sexual relations, others hesitated to acknowledge that they had unwanted sex with black men, knowing the consequences these men faced in the racist South.

Aside from the blurred lines of sex among acquaintances, anxiety about personal safety made American women ripe for feminist analysis of sexual violence. In 1971 Susan Griffin published an essay in the radical press explaining that the fear of rape was a “daily part of every woman’s consciousness.” She exploded each of the myths about rape in American culture, addressed the legal obstacles to prosecuting sexual violence, named white male privilege as the heart of the problem, and recognized the particular vulnerability of women of color and the costs of the myth of the black rapist. Several years later journalist Susan Brownmiller elaborated many of these points in “Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape.” This best-selling book explored the power dynamics of rape in history, law, and culture; set an agenda for legal change; and alerted the public to the nascent feminist anti-rape movement.

In the early 1970s this new political campaign coalesced rapidly. Along with reviving many past strategies, it broke through earlier silences and created innovative approaches that went beyond legal reforms. Reflecting the radical feminist emphasis on moving from personal experience to political action, the movement gestated in consciousness-raising groups in which women shared their experiences and then culminated in political demonstrations. A public “speak out” during a conference on rape held in New York City in 1971 jump-started the process. Rape, the women attending agreed, was a crime of violence, rather than a sexual act, and both law enforcement and women’s groups needed to address the problem.

Grassroots women’s groups devoted to stopping rape sprang up across the country, from Washington, D.C., to Seattle. In many communities feminists created rape crisis hotlines that women could call to report assaults. On a far broader scale than their predecessors in the 1890s, they established rape crisis centers, which soon became a cornerstone of the movement. By 1976 over four hundred centers provided counseling, social services, and legal support for women who had experienced sexual violence. The anti-rape movement redefined women as “survivors” rather than “victims” and renamed behaviors once associated with the masher as “street harassment.” While they often targeted men as the source of the problem of sexual assault, they also called on male allies to organize to help change gender conventions that contributed to sexual violence.

Quite a few of the methods of the feminist anti-rape movement resembled earlier campaigns. Like newly enfranchised San Francisco women in 1911, Wisconsin feminists initiated the successful recall of a judge, Archie Simonson, in 1977. The judge had treated several young rapists leniently and blamed their crime on women’s clothing. After the petition campaign, voters elected a female judge to replace the deposed Simonson. Like suffragists who championed female police authority, feminists questioned police responses to rape and called for the presence of female officers when women reported assaults. Groups such as Women Against Rape encouraged self-defense classes that incorporated the confidence-building goals first articulated during the response to the masher, when women trained athletically to claim their space on city streets. New strategies proliferated as well. During Take Back the Night marches, women walked en masse through dangerous urban districts to signal the strength of numbers and a refusal to limit their mobility. In response to both rapes and a series of murders of black women, more than five thousand joined the 1979 march in Boston. Earlier efforts relied on donations and volunteers, but in an era of government funding to address urban problems, local groups began to apply for federal and state grants to support their anti-rape programs.

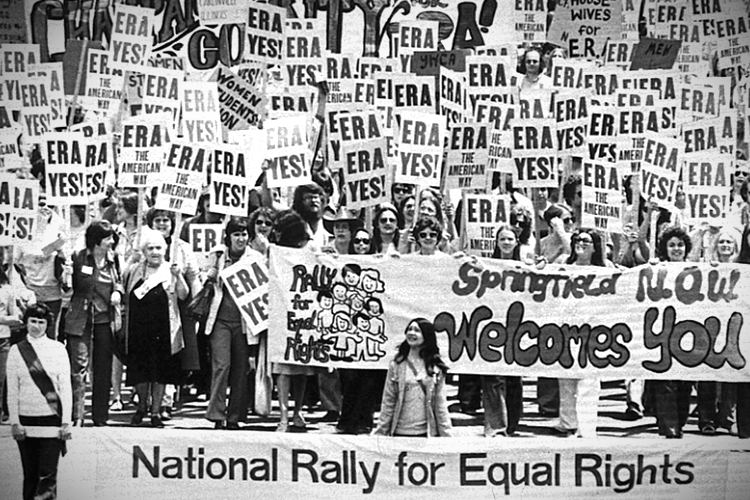

Along with radical local activism, on the national level liberal feminists who favored equal rights legislation turned their attention to rape statutes. In 1973 the National Organization for Women (NOW), founded in 1966, created a Rape Task Force to propose revisions to state laws. Women’s groups challenged requirements of corroborative testimony and the use of “utmost force” to prove resistance. They called for revisions to police procedures and to the ways hospitals responded to assault. The concomitant push for full jury service for women, as well as the growing number of women lawyers and judges, seemed to fulfill suffragists’ hopes for more equitable treatment in the courts. As the momentum for legal reform spread, established institutions weighed in as well. In 1975 the American Bar Association (ABA) approved a resolution on rape laws that urged the revision of corroboration requirements and penalties, as well as the establishment of treatment centers “to aid both the victim and the offender.” The ABA resolution further pointed to a trend toward gender-neutral rape law when it called for “a redefinition of rape and related crimes in terms of ‘persons’ instead of ‘women.’” Gender-neutral statutes, once a radical proposition of supporters of the unpopular National Woman’s Party, spread through the country after the 1980s.

Though white women dominated both radical and liberal feminist organizations, women of color increasingly mobilized against rape, independently and in coalition with other groups. Following the tradition of Ida B. Wells and the black women’s club movement at the turn of the twentieth century, influential African American writers such as Angela Davis and Alice Walker called attention to the intersections of gender, race, and sexual violence. Analyzing the trial of a southern black woman, Joann Little, for murdering the white jailer who raped her, Davis called on the antiviolence movement to be “explicitly antiracist.” In the 1970s the National Black Feminist Organization co-sponsored events with New York Women Against Rape to create a more diverse movement than first-wave feminists had known. Boston feminists created the cross-race Coalition for Women’s Safety, which recognized that “women of color are singled out as targets of violence both because of their race and their sex.” Groups around the country addressed this problem. In East Los Angeles, Chicana activists established a bilingual rape hotline in 1976 to serve Spanish-speaking victims, while the Compton YWCA developed a rape crisis program to serve the black community just south of Los Angeles. Both black and Latina feminists helped to expand the services of the Washington, D.C., Rape Crisis Center and to diversify its staff. In 1980, under the leadership of black activist Loretta Ross, the Center organized a National Conference on Third World Women and Violence.

Despite these alliances, feminists replayed many of the racial tensions that characterized earlier anti-rape movements, as the response to Brownmiller’s book illustrated. “Against Our Will” exposed the injustices of lynching and the rape of black women, but her chapter on race raised hackles. Brownmiller questioned the continuing preoccupation of the American Left with the defense of accused black men. She also emphasized the rhetoric of radicals such as Eldridge Cleaver, who seemed to embrace rather than reject the myth of the black rapist. Most disturbing, perhaps, was her suggestion that Emmett Till had been trying to exercise male privilege when he whistled at a white woman, the act that led to his brutal murder by southern whites. Feminist scholars such as Angela Davis and Bettina Aptheker questioned “the racist dimensions” of Brownmiller’s book and accused her of distorting the historical record. Women active in the civil rights movement condemned her for “fanning the fires of racism.” The controversy highlighted a contradiction that Aptheker identified “between being able to resist the racist use of the rape charge against Black men, and at the same time counter the pervasive violence and rape that affects women of all races and classes.”

This conflict recurred as the anti-rape movement pressed for legal reforms, such as rape shield laws that would make a woman’s past sexual history inadmissible as evidence. Resting on the chastity requirement, such testimony potentially deprived sexually active women of legal protection. To remedy this limitation, Michigan enacted a rape shield law in 1974, a reform soon adopted by other states. Feminists and civil libertarians who were concerned about the rights of defendants, many of them aware of the legacy of Scottsboro, expressed concern that these laws would eliminate a useful tool for countering false charges. The controversy flared up within the ACLU, where members debated the relative importance of protecting the sexual privacy of women and protecting the civil liberties of defendants, who remained disproportionately black men. The compromise that emerged in the ACLU called for closed judicial hearings to determine the relevance of a complainants’ past sexual history. The ACLU opposed the federal rape shield law introduced in 1976 by Representative Elizabeth Holtzman, which became part of the Privacy Protection for Rape Victims Act that Congress passed in 1978. That statute compromised by allowing evidence only about a complainant’s sexual history with the defendant, excluding any other past relations.

Feminists and civil libertarians did agree on other reforms. Both groups questioned the usefulness of the death penalty for rape and believed that reducing prison sentences could encourage convictions. In an amicus brief filed on behalf of both NOW and the ACLU, feminist attorney Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s arguments against capital punishment included the grounds that by treating women as the property of men, the death penalty for rape was a remnant of patriarchy. In 1977 the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the death penalty for rape. At other times feminists split between those who sought expanded state regulation and those who wanted to protect freedom of sexual expression. Such was the case in the controversy over pornography. Some radical feminists believed that pornographic depictions, particularly of violent sexual acts, incited rape. As Andrea Dworkin put it, “Pornography is the propaganda of sexual terrorism.” When Dworkin and legal theorist Catharine MacKinnon introduced municipal statutes that would allow women to sue distributors of pornography for violating women’s civil rights, many feminists joined with the ACLU to reject this strategy as a dangerous form of censorship.

In perhaps the most striking divergence from earlier activists, feminists now confronted the marital exemption. Anarchist free lovers had long questioned the sexual rights of husbands, but suffragists had avoided a direct confrontation with the institution of marriage. Since the 1920s marital advice literature frowned upon the exercise of a husband’s right to sexual services, yet the 1962 Model Penal Code left intact the marital exemption and extended it to common-law couples. Given the radical feminist analysis of power relations within the family and the emergence of a movement against domestic violence, the time seemed ripe for reevaluating this remnant of coverture.

Elaborating on arguments initially made by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Emma Goldman, feminists called for sexual self-sovereignty within and outside of marriage. Influenced by writers such as Brownmiller, legal scholars gradually began to question the marital exemption, paving the way for legislative change. South Dakota first outlawed marital rape in 1975. The following year the ACLU approved a resolution calling for the redefinition of rape that addressed the exemption. In 1984 the New York State appellate court rejected the distinction between marital and nonmarital rape and declared the exemption unconstitutional. In language that incorporated the new feminist definition of rape, the judge explained that a “married woman has the same right to control her own body as does an unmarried woman.” By the end of the century most states had modified their rape laws to include relations between spouses. The new laws often set a higher standard of force and lesser penalties for rape within marriage, but they signaled an important cultural as well as legal shift. Along with legal change, feminists tried to educate the public about the problem of marital rape, a major focus of the National Clearinghouse on Marital Rape, founded in 1978.

Turning attention from stranger rape in the public sphere to unwanted sex in the private family helped expose the sexual abuse of children. For decades the media had represented the violent psychopathic stranger as the major sexual risk to children, an image closely linked to that of the homosexual predator. In the 1970s, opponents of the fledging gay rights movement successfully rallied under the cry “Save the Children” to repeal several of the first municipal statutes guaranteeing the civil rights of gay men and lesbians. At the same time, however, disbelief of children’s accounts of unwanted sex within families sustained the historical silence about incest. Then a spate of feminist analysis and personal testimony began to challenge these patterns and uncover the extent of child sexual abuse.

The title of Florence Rush’s book, “The Best Kept Secret,” epitomized the new approach. The molestation of children was far more widespread than previously thought, Rush explained, but it remained unreported in part because assailants often silenced children by threatening further harm if they revealed the abuse. Moreover, she argued, incest was not simply a private family affair but arose from broader cultural patterns that eroticized children and reinforced patriarchal authority. Unlike the child-blaming authorities of the past, feminist psychologists now questioned Freudian doctrine about childhood fantasies. Social scientists began to document the extent of the problem. One study suggested that as many as one-fourth of North American children had experienced some form of sexual abuse. Novelists such as Toni Morrison, Dorothy Allison, and Jane Smiley portrayed the dynamics and the personal costs of incest for women from a range of race and class backgrounds.

The vast majority of assaulted children were female, but by the end of the century more men were acknowledging their histories of having been sexually abused in families, schools, and religious institutions. The literature showed a pattern in which men who held positions of authority—including teachers, coaches, and clergy—took advantage of both girls and boys in their charge. Although women only rarely abused children, the recognition that some did so contributed to an analysis of power, and not only of gender, as the underlying context for child sexual assault. New understandings of male vulnerability encouraged a redefinition of rape though gender-neutral laws. The revelations of sexual assault against children, along with lawsuits that held individuals and institutions responsible, put pressure on schools and hospitals to identify signs of abuse and establish reporting guidelines. In the late twentieth century, speaking out and child assault prevention programs began to displace the silence of the past.

Like the attention to familial relations, the identification of “date rape,” or “acquaintance rape,” expanded the definition of assailants beyond the historical stereotypes of black, gay, or psychopathic men. In the nineteenth century, antiseduction and age-of-consent campaigns targeted white men who sexually coerced young female acquaintances. By persistently using the term rape to describe these behaviors, second-wave feminists took the redefinition process further. Like incest survivors, women who had unwanted sex with men they knew began to disclose their experiences. Social scientists documented the scope of unreported, unwanted, and often forceful sexual relations among the young. In one study, over a third of the women surveyed reported rape or attempted rape by an acquaintance, compared to just over 10 percent who identified strangers as their assailants. Yet, as the title of another exposé indicated, they “never called it rape.” Neither did the men. In response to these studies and to complaints from students, their families, and lawmakers, schools and colleges began to articulate policies that would undermine tolerance for this conduct and undercut the “no means yes” construction of sex. At the same time, a men’s antiviolence movement committed to ending coercive behaviors spread from campuses to communities. Men had been active in supporting earlier anti-rape movements, but now they organized as men who refused to objectify women sexually and who sought to undermine gender norms that privileged male aggression.

By the 1990s the modern campaign against sexual violence had achieved an impressive agenda. Most states had revised their sexual assault statutes; nonconsensual sex within marriage and between acquaintances could now be defined as rape; educational and medical institutions began to take more responsibility for identifying assaults; and fiction, film, and personal memoirs addressed the power dynamics that feminists identified as central to both coercive and violent sexual encounters. Internal disagreements among feminists persisted, but their overall analysis moved beyond the earlier focus on protecting women’s purity, beyond demands for formal political rights such as suffrage and jury service, and toward the assertion of women’s right to sexual independence.

Excerpted from “Redefining Rape: Sexual Violence in the Era of Suffrage and Segregation” by Estelle B. Freedman, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2013 by Estelle B. Freedman. Used by permission. All rights reserved.