Yesterday I argued that President Obama is approaching the coming fights with the GOP over funding the government and increasing the debt limit in exactly the right way — and moreover that getting cocky and firing off demands of his own would likely backfire.

But I still detect a couple of sources of unwarranted liberal anxiety and they both deserve attention and serious treatment.

The first — again! — comes from the New Republic’s Noam Schieber, who acknowledges it would be a blunder for Obama to demand that Republicans increase the debt ceiling prior to or at the same time as they extend funding for the government. (Point, Salon.)

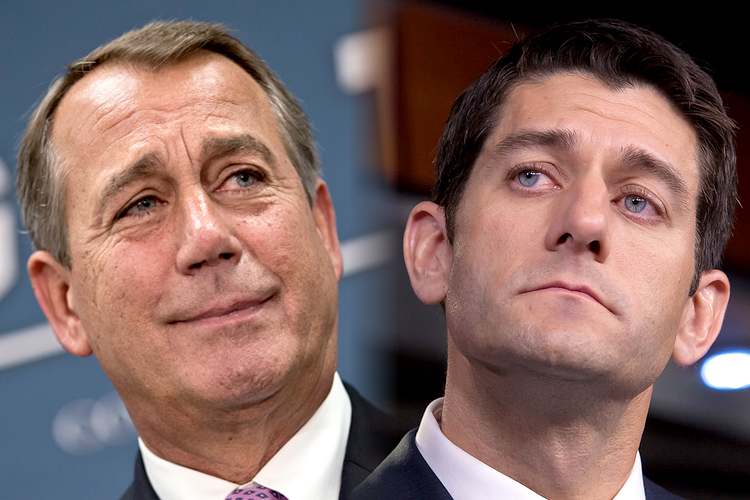

But he also highlights an extremely interesting legislative dynamic unfolding before our eyes. Here’s how I’d summarize it: To the extent that all these budget fights are playing out simultaneously, even if they’re playing out in different arenas, political actors can mush them together, and thus obscure the real, discrete tradeoffs. That means House Speaker John Boehner can characterize any concessions he gets from President Obama in a hypothetical plan to turn off sequestration as a “price” Obama paid for increasing the debt limit.

This, Noam points out, would allow Boehner to rehabilitate the dangerous idea that the debt limit is a legitimate source of leverage for a congressional majority to wield against the president of another party.

As long as the debt ceiling is alive and they’re allowed to believe it’s in play, they’ll believe they have leverage…and will demand far deeper cuts than Obama can possibly give them. Likewise, any deal that allows Republicans to say “we won these concessions in exchange for raising the debt ceiling” will only encourage further debt-ceiling extortion in the future, a terrible practice to encourage (at least any more than Obama already has, which is quite a bit).

Noam’s proposes a simple solution: Obama should zero in on the debt limit. He should put all other negotiations in abeyance until Republicans increase the debt limit without getting anything in return. (Or at least nothing that can be characterized as a concession, without inviting howls of laughter from the public.)

That would end the default threat forever.

Personally, I have no objections to this idea. But here’s why Obama might feel differently: Rolling the GOP on the debt limit in such an aggressive way would both destroy the goodwill he’s built with a number of Senate Republicans, and eliminate a key source of pressure on the House to accept a possible budget deal with those senators that includes concessions from both parties. This is the “permission structure” Obama’s spent months building. It collapses if he pantses Republicans in the way Noam suggests.

If you want to kill that deal, then Noam’s plan is the way to go. But if you’re mainly concerned about the precedent-setting power of Boehner’s debt limit wordplay, then I don’t think you have much to worry about. To reiterate, the deal Obama wants would swap sequestration for a mix of cuts to social insurance programs and tax increases on high-income earners. Whatever you think of the tradeoff, and whether or not the debt limit is the forcing mechanism that makes it happen, that’s his goal. If Boehner then wants to claim that an entitlement cut — say, reducing Social Security cost of living increases — is the “price” he extracted from Obama for increasing the debt limit, he’s free to try. But if it’s paired with a tax increase who’s going to believe him? Who’s going to see it as anything other than a budget deal? Nobody. And the next time we approach the debt limit Obama can go right back to ignoring Boehner’s idle demands.

There is a nightmare scenario, though. And that’s if Obama decides to cave on his insistence that sequestration be replaced with a mix of cuts and revenue. If in the context of a debt limit fight he agrees to drop the revenue demand, he’ll have lost the sequestration fight, and done so in a way that allows Boehner to characterize it as a debt limit mugging. Even if Obama’s economic aides think that’s a worthwhile trade on the merits, it would constitute a huge political defeat and create a monstrous precedent for future debt limit fights.

Which is why I can’t fathom it happening. It would be an act more desperate than anything Obama entertained in the darkest days of 2011. Democrats in Congress would revolt. I could even imagine Democratic 2016 hopefuls, up to and including Hillary Clinton, inveighing against it publicly. I’ve neither seen nor heard any evidence that it’s under consideration.

So bracket that for now and consider Ezra Klein’s concern, which is rooted in the observation that the parties’ red lines in debt limit negotiations, and their broader ideological commitments, have no overlap. “Republicans say they will raise the debt ceiling only in return for significant budget concessions,” Ezra writes.

But that’s not really true. The actual line is as follows, articulated most recently by John Boehner himself: “I’ve made it clear that we’re not going to increase the debt limit without cuts and reforms that are greater than the increase in the debt limit.”

That was the line last time around, too. But when it came time to make good on the demand, they just stretched the definition of the word “reforms” past the point at which it had any bearing on policy. And when the deadline is upon us, and a broader deal hasn’t materialized, I’m confident they’ll do it again.