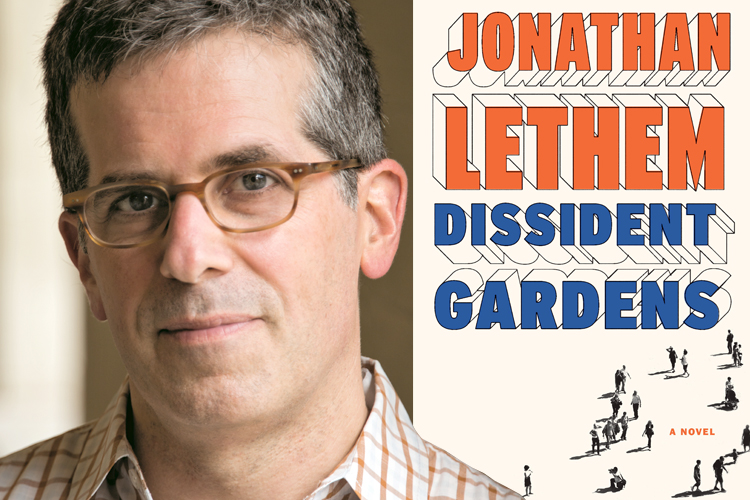

Jonathan Lethem is about to release his most ambitious book yet — no small statement.

The author of much-hailed novels, including “Motherless Brooklyn” and “The Fortress of Solitude,” returns with “Dissident Gardens,” a sprawling, time-hopping novel that takes on the history of intellectual protest, and of New York, in the 20th century. Extrapolating outward from a loosely defined family, Lethem’s book finds room for New York baseball, quiz shows, race relations, Archie Bunker, homosexuality, academia and a misguided jungle adventure.

Narrowly defined, though, “Dissident Gardens” is the story of a mother and her descendants — Rose Zimmer, an elderly communist; Miriam, her daughter and a societal dropout; Sergius, her grandson living in or near the present day; Cicero, the gay son of Rose’s black lover, who retreats into literary theory as a means of abstaining from answering the identity questions that have plagued him through his life.

Lethem, perhaps the closest thing New York has to a bard, lives in California now; he spoke with Salon by phone about the perils of writing an “ambitious” novel, the degree to which protest culture is part of our everyday lives now, and whether he’s annoyed to be compared with that other Jonathan.

The world of activism in particular isn’t necessarily foreign to you. I’m wondering the degree to which there is any personal or historical reason for the divisions therein interesting you quite so much.

Well, yeah, many. I’m not sure if I can nail it with a simple reply, but I’m sure it’s personal, of course it is. And it comes from the way that my family life was a whole allegory, maybe a whole pile of allegories, about belonging and exclusion. My mother was an outer-borough kid who dropped out of college and sort of floated — she was super culturally savvy and comfortable in the sense that she also was someone who never — she’d not gotten a college degree, she’d had no career, she never got started making her way into the world in any kind of career. She was a kind of a fascinating mix of sophisticated and naive and living by her wits. She was sort of a feral person, in some ways. Her mother, my grandmother, was from a large Jewish family with lots of marriages and cousins — I have acres of Jewish cousins — and yet somehow my grandmother exiled herself within the tribe of her own family. She was an embattled dark horse who couldn’t come in from the cold.

And at the same time, I think, my father was a strange mixture — he was a Fulbright scholar, he used to be a college professor, but he dropped out of his liberal career in order to be a carpenter. His own political life, with his passions around war and activism, this was incompatible with functioning within an institutional world. And so growing up in Brooklyn, in this very complicated, fascinating borderline zone in South Brooklyn, that I’ve written about elsewhere, of course, I saw myself as heir to, entitled to, the great story of being a New Yorker, and somehow, also, damned to this marginal, dystopian quadrant, a dead zone within the city. And all of these things made me feel the possibility of life being a perplexing story of being on the outside looking in, always in a very charged, marginal position. It did me well as a novelist, it meant I was aspiring, a watcher, a critic. An invisible man in a lot of contexts.

The book presents something of a history of intellectualism and communism and what I would broadly and perhaps somewhat inaccurately describe as activism and protest. It seems as though that sort of spirit is less present in the U.S. today than it was in many of the time periods the book depicts. Do you think there is as much of an activist spirit today as there had been in the past?

Well, you probably have to think that. Certainly, in this book, right after the ’30s, and leading into the ’30s, and the ’60s, I mean, obviously, there is a sense that we all have that there is a type of activist chapter, if you’re old enough, you live through and your parents live through that nothing can touch.

And I think there is something to that history, but I also think that the larger scheme of American history includes all sorts of powerful ideas and forces that are in a way identified as being political activism in the same way.

I call it “Dissident Gardens” because for me, it’s a lot about the feeling that being in exile within the culture, on the margins, is itself a powerful part of American life, at least that’s been my experience of it, and the middle of the ’60s was a time when a lot of people thought they were all taking the same journey. And that’s been fragmented in all sorts of tragic ways, but it’s also gone underground into people’s lives, in a lot of different ways. And it erupts, it erupts in these weird ways.

About the fragmentation of a sort of unity that was intellectually felt among many outsiders after the 1960s: I know that you had read at Occupy Wall Street and that a criticism of Occupy was that it fragmented in exactly a manner similar to the fragmentation of protest movements in the 1960s, that there were too many diverse causes that were not integrated into a unitary ideal. It seems to me that this sort of thing keeps reiterating itself.

Well, I don’t have any great solutions. I’m not someone who can provide solutions for the things that have gone wrong with leftist movements and I don’t even …

In a way I’m too moved by them, I’m too sensitive to these movements to simply make these kind of structural critiques, and so the fragmentations are a betrayal. And I feel that way about Occupy if I’m feeling tragic about it, but I also think that, yeah, that comparison is really interesting. People say that Occupy Wall Street is a super-compressed ’60s because of the nature of how quickly it evolved, then fragmented, then integrated. It went underground and into ourselves and into our lives even as it appeared to dissolve or turn into pieces.

With the ’60s, you can look at something happening now and just be really prosaic about political facts — something like gay marriage, you know, would be unimaginable without the ’60s. Utterly, in a sense, it’s a culmination of one tactic of that struggle.

And so Occupy is sometimes a super-compressed version of the same sort of sense. It was very cool to me, not that it was meant for me personally. I also was really moved, not being able to be inside, because it was an on-the-ground experience, you had to be in a camp, and that was taken very stirring, very interesting, very poignant, because of its being based upon structural exclusion even though it was trying to be inclusive. I’m still thinking about it.

I think only in a kind of journalist’s sense is it over. I think the provocation, the possibilities that it represents are kind of … we’re moving outward from that moment.

The gay rights struggle, as you mentioned, is particularly interesting in the context of this novel, as, throughout the novel, the gay character Cicero feels out of place, uncomfortable, and it was just interesting to me that these characters who can be so liberal for their time are not enlightened in whatever way we consider ourselves to be. They don’t necessarily cohere with 2013 liberal values.

Yeah, it’s something I was feeling into, just the way that people can be so enlightened and so idealistic and so cynical in such rapid and conflicting, contradictory ways; Rose, one of the central characters of the book, she’s dedicated her life to this high class of socialist egalitarian people and her sex life is that she loves a man in uniform. She’s into authority. I think that what I find in myself and my friends and my family — we’re muddled. We sometimes can sort of think that we can stand entirely on our best idealistic beliefs and live them and embody them and sometimes we run screaming from the implications of our own freedom.

I feel as though this book depicts really well a tribalism among liberals, in particular the feelings of Cicero, who for various reasons feels perpetually alienated. At least in the time you depict, you frame activist characters as very divided by race in particular, and also by other factors as well. Is that division still the case?

I think I recognize what you’re talking about, and it’s something so deep in my work that I have trouble even noticing it. Because it transcends the political life of these particular characters, I think about — I write about — sects again and again, so it’s community and exclusion and casting oneself away from the available community, whether it’s a family or a neighborhood or whatever it might be.

Tell me a little bit about writing about New York, once again, while living in California.

It’s a compulsive pattern, if you really look at it. I ran away from New York at 18, went to college in New England, and then when I bombed out of college I went to California, where I was for 10 years, that’s where I began my writing life. For a long while I didn’t think I would be returning to New York. I felt agnostic growing up. And I wouldn’t have ever believed if you’d told me how much I’d end up writing about the place. But I did circle back in various ways, literal and metaphorical, and become immersed again in the life of the city, and it turned out to be the great love-hate relationship of my life, and one that unearths so much material for me. When I decide I’m going to write about the city, my work comes alive for me in a certain way; it’s crazy to take it for granted.

But, for instance, “The Fortress of Solitude” was written mainly in Toronto. I had an address in Brooklyn and people probably thought I was there more than I was there. There’s something about the act of exile that leads me to turn away from New York and write my way back from afar.

I’m interested in the degree to which you’re seen as someone who sets out to write, and successfully does write “big” or “ambitious” novels. What do those terms mean to you? Do you think they’re useful?

Yeah, big and ambitious [laughs]. Yeah. Well, I was just watching Richard Pryor, and he says, “When you’re dating a white woman, and people don’t like it, you can’t really pretend. You can’t go, ‘Oh, she’s not with me.’” You write the big, ambitious books, right? Well, I guess they are.

But it took me a long time, first of all, but I still think I have a failure to identify even with what I make, with what — certainly in the last four books, are easily accused of that. I think I had to, of course, take a long time to think about form — people don’t understand how that works. I think my appetite as a reader was more proportionate with more formally tight books, and to learn to love books that were called the baggy monsters, I had to not just read them and find examples that I loved. I was kind of scared of them for a long time. I was like, “OK, great, it’s an amazing experience as a reader, but how do you make one of those, and believe it while making it?”

And it took me a very long time to do it. I didn’t do what Norman Mailer or Jonathan Franzen think you’re supposed to do, which is write one of those things to begin with. I wrote five books that were tidier, and that’s disguised a very, very slow evolution in my craft, I guess. It wasn’t about fishing for it, or what I thought was the most important thing to do. It was about what I was capable of. And what I was increasingly interested in was this way of making something too big-time for the reader or the writer, that you fell into, that you were lost inside for a while. And I really took on those trends, as kinda like an object, almost as if I were a visual artist or something. It’s like a kind of object that started to put on weight. It was exciting.

I don’t really think of that as a hot-air literary morality — Oh, the truth is always contained in those giant novels — or as a kind of macho ambition. It’s just to me about the things that can happen, the kinds of feelings and experiences that can be enacted for the reader, inside of this structure. That’s what I’m turned on by.

I feel as if people describe you in one breath with Jonathan Franzen, and I’m wondering if you ever wish your name was Bob. Not that there’s anything wrong with him, but you guys aren’t necessarily twins.

Let’s rename him. He should be Bob Franzen. He should be Bob. No, I think — I think it’s just fine. It’s not — for me, worrying about that, where there are so many things to worry about, where I have to be conscious at every level of extraordinary proportion, that my work is taken so seriously, maybe excessively seriously. It’s one of those things that people are knitting their brow about. But I have every privilege, so if my privilege comes in the same breath as a guy who sells 10 times more books than I do but we both have the same first name, what of it? That’s not a problem.