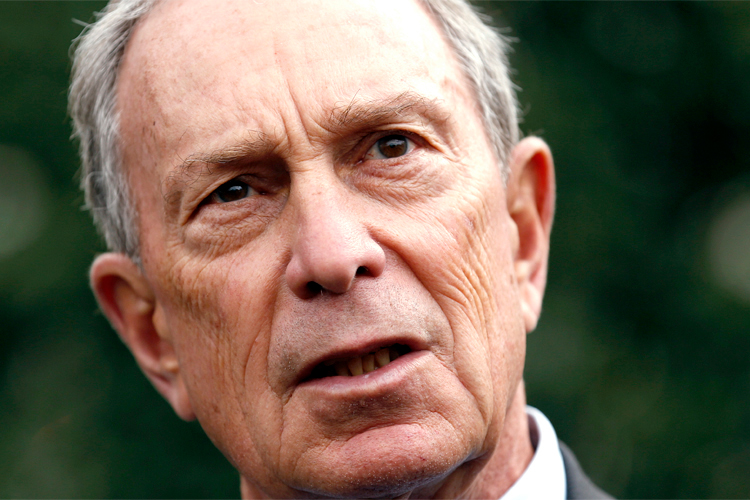

Over the weekend, New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg drew attention for allegedly suggesting that Democratic candidate Bill de Blasio was running a “racist” campaign in his bid to succeed him. This wasn’t necessarily the most revealing thing he said in the interview, and it’s not even clear he meant to use that word.

But the flap did reveal a central truth.

Michael Bloomberg is not enjoying de Blasio’s campaign — and there’s a pretty good reason why: The Democrat’s campaign represents one of the first sustained, publicly damaging attacks on his mayoralty that the billionaire has not been able to silence using an arsenal of personal relationships, political leverage and lots of money. For Bloomberg’s political and policy legacies, de Blasio’s impassioned critique (and its dramatic political success) pose a formidable threat he has not faced before.

First, some context. When Bloomberg entered office in 2001, the default setting for running City Hall was that at any given moment, you were likely to be hated by a sizable portion of the city, no matter what you did. It simply wasn’t possible to run New York in a way that would avoid vocal criticism from editorial pages, unions, business elites, leaders of numerous ethnic and cultural communities, nonprofits, good government groups, other politicians, the city council, and the organization of the opposition party (let alone your own) all at the same time.

To some extent, Michael Bloomberg managed to change that — partly through laudable ways, partly through less laudable ones. But either way, the result was he was able — until now — to prevent a climate of noisy pushback that most New York mayors do not.

Since his first term, the editorial pages helped set the tone. Sure, the New York Post, Daily News and New York Times hardly agree on anything. But all have owners who admire the fellow media-owning executive Bloomberg. While each took issue with him occasionally, all three would not only effusively endorse his second term, but pave the way to overturn the law that helped him land a third one (and each endorsed his tacit choice for a successor, Christine Quinn, this year).

Politically, Bloomberg wasn’t going to have unions all eating out of his hands, but he did adeptly and understandably leverage his office’s power to keep several of them content (enough). For example, when the Hotel Trades Council wanted special permits to curb the proliferation of low-cost, anti-union hotels, Bloomberg’s administration went to battle for them. The result was a powerful alliance that would help insulate him from anti-labor charges — and net him a key backer for his reelection.

Another potentially nettlesome critic might have been the city council speaker. Here again, he used the political leverage of the position skillfully, forging an alliance with Quinn and making clear that a partnership with him would serve her well and perhaps lead to an endorsement to succeed him (which seemed like a better deal at the time). Far from serving as a Bloomberg critic, the result was a cooperative relationship where, as Bloomberg explained in the controversial New York magazine interview, Quinn prevented many bills anathema to him from coming to the floor.

But it wasn’t always political leverage that the mayor used to avoid attacks on his mayoralty.

Back in 2006, I was the communications director for the New York State Democratic Party. While we rarely attacked Bloomberg that year — having served two terms, he’d never be up for reelection again, we thought – one act went too far. In the middle of the close battle for control of the U.S. House (in which Democrats would regain power for the first time in 12 years), the NYC mayor endorsed and cut a TV ad for Republican Chris Shays in a Democratic district that was a prime pickup opportunity (Shays would win that year but lose in 2008).

In response, the party decided to put out a mild, pro forma statement knocking the mayor. Within a few hours, a top aide to Bloomberg called the office screaming — and vowed to give 500,000 Bloomberg bucks to the state Republican Party, because of the press release.

Sometimes the exercise of financial leverage was done more proactively. When he wanted to ensure good relations with influential African-American clergy, the mayor’s considerable financial leverage was not lost on Rev. Calvin O. Butts III. As the Times reported, during Butts’ endorsement of Bloomberg in 2009:

[Bloomberg’s African American opponent Bill Thompson] was furious at the betrayal. But what he did not know was that Mr. Bloomberg gave a $1 million donation to the church’s development corporation — roughly 10 percent of its annual budget — with the implicit promise of more to come.

“What could I say to a man who was mayor, and was supportive of a lot of programs that are important to me?” Mr. Butts said in an interview before he endorsed Mr. Bloomberg.

When the mayor faced massive criticism by seeking to override two public referenda and allow himself to run for a third term, he not only got Quinn and the aforementioned newspaper-owning friends to back him – but an array of city nonprofit and charitable organizations testified on his behalf. Again, there were millions of reasons why, the Times explained:

Michael R. Bloomberg, who says he strictly separates his philanthropy from his job as mayor of New York, is pressing many of the community, arts and neighborhood groups that rely on his private donations to make the case for his third term, according to interviews with those involved in the effort.

As opposition mounts to his plan to ease term limits, those people said, the mayor and his top aides have asked leaders of organizations that receive his largess to express their support for his third-term bid by testifying during public hearings and by personally appealing to undecided members of the City Council.

…

“It’s pretty hard to say no,” the official said, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of upsetting the mayor. “They can take away a lot of resources.”

Of course, the most likely situation in which a mayor’s record would receive a blistering attack would be during a reelection campaign. But Bloomberg not only spent nearly $100 million in each of his reelections to effectively drown out the opposition, he also successfully persuaded many of his wealthy friends not to give to those opponents – thus ensuring there would be no sustained, vocal attack on his mayoralty.

You might expect a good government group to attack the mayor for some of the above practices. But after his company had donated to it for years, one such group, Citizens Union, actually endorsed his reelection (despite strongly opposing his term limits gambit), in a press release filled with caveats and explanations. (The move itself would lead to great internal criticism.)

One last example: Bloomberg deserves credit for his strong advocacy on certain liberal causes like gun safety measures. But why did he rarely get flak from the right in New York? One reason may be that doing so would require the local Republican and Independence parties to betray someone who was extremely kind to them financially.

So, yeah, Bloomberg has been pretty successful in using his arsenal of financial and political leverage to discourage dissent.

Here’s where de Blasio comes in.

Unlike with so many other players who have come before him, Bloomberg can exercise no political or financial leverage over the Democratic front-runner.

Formally endorsing Quinn in the primary – once seen as an assured outcome – would actually help de Blasio in the Democratic primary, where voters have mixed feelings about the mayor (and seem to be penalizing Quinn for her relationship with him). Saying nasty things about de Blasio, as the mayor did in the interview published this weekend, also seems to be helping him. And with both men soon vacating their current offices, there isn’t much Bloomberg can do to him governmentally (e.g., cut his budget) at this point.

As for money, the mayor could theoretically empty his wallet and fund a PAC’s ads against de Blasio. But he hasn’t so far, and for good reason: Doing so might very well boomerang on him in much the same way his verbal attack has. Without the political leverage to quiet him or the opportunity to financially drown him, he’s been left to deploy his skilled aide Howard Wolfson to bash de Blasio and defend his legacy in various forums. Wolfson’s good at this, but compare it to the arsenal of tools the mayor previously had to protect his image, and it barely makes a dent. Even with the city’s three biggest papers endorsing Quinn, de Blasio’s only seemed to get stronger.

The result is that the Democrat has launched a sustained, vociferous attack on the Bloomberg legacy – on everything from his economic philosophy to his stop-and-frisk policy – and it has stuck. Over the course of the last 12 years, it’s one of the only lengthy, publicly audible excoriations of his performance and legacy that the mayor could not quell – whether through intimidation, punishment or reward.

Seen in this context, it makes sense that Michael Bloomberg would be upset at Bill de Blasio. His political and policy legacies are facing a firing squad and — for the first time ever — he may be powerless to stop it.