The question of human nature reliably polarized political philosophers across many centuries and several oceans. One group of these thinkers viewed people as innately cooperative or potentially compassionate; another group argued for an inherently competitive human nature. This division begs the question of whether the split corresponds to a difference in left-right political orientation. In some cases, such as that of Marx, there is little doubt about where to place the thinker on the political spectrum. In other cases, however, identifying the ideological leanings of historical figures is a task better left for professional historians.

In any case, history’s great political philosophers are not the only people who disagree over the nature of human nature; the human-nature question is a perennial problem that also divides contemporary politicians and ordinary citizens. Below we’ll explore what modern political psychology has discovered about this ancient philosophical puzzle. Statistical tools and laboratory experiments can determine precisely how an individual’s perceptions of human nature can predict his or her political orientation.

But first, a very brief tour of more recent political leaders and movements reveals a notable trend: conservatives tend to view human nature as competitive, while liberals are more prone to perceiving human nature as cooperative.

In 1964, the Republican Party nominated Arizona senator Barry Goldwater as its candidate for the U.S. presidential race. Although Goldwater lost the race to Lyndon Johnson, he set the ideological tone for the resurgence of right-wing politics in the 1960s, which earned him the nickname “Mr. Conservative.” The book that launched Goldwater to national prominence was his “Conscience of a Conservative” (1960). This widely read booklet laid out the senator’s views on numerous controversial political issues of the day. It resonated with millions of conservatives across the country.

On the topic of human nature, Goldwater’s book addressed “the corrupting influence of power”: “the natural tendency of men who possess some power,” he wrote, is “to take unto themselves more power. The tendency leads eventually to the acquisition of all power.” In Goldwater’s worldview, man’s competitive nature had no limit.

In 1980, when the conservative politician Ronald Reagan asked Americans for their votes at the end of his presidential campaign, he said: “As you go to the polls next Tuesday and make your choice for President, ask yourself these questions: Are you better off today than you were four years ago? Is it easier for you to go and buy things in the store than it was four years ago?” David Sears, a political scientist at UCLA, has pointed out how right-wing politicians like Reagan tend to make more appeals to the public based on the assumption of a self-interested audience.

Sears has contrasted Reagan’s speech to that of the Democratic president John F. Kennedy. In 1961, Kennedy famously entreated his “fellow Americans [to] ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” In Kennedy’s speech, the liberal president invoked a cooperative human nature.

In the late 1960s, left-wing peace activists in U.S. colleges were demonstrating against their country’s war in Vietnam. Psychologists who analyzed the ideological themes of their protests noted “a strong antipathy to self-interested behavior.” When these liberal students took psychometric tests, they measured significantly higher than nonactivists on humanitarianism, which included a strong “desire to help others” and a valuing of “compassion and sympathy.” The researcher noted that the most radical left-wing activists also had unrealistic expectations about how cooperative others would be in supporting them when they graduated; this group of students planned to continue to “work full-time in the ‘movement’ or . . . to become free-lance writers, artists, [or] intellectuals.”

Even though our leaders’ perceptions of human nature are normally less skewed, their biases can nonetheless have wide-reaching policy repercussions. In 2009, the conservative politician George W. Bush had finished eight years as president of the United States. Barack Obama then assumed office, bringing a liberal administration to the White House. Obama apparently believed that his predecessor’s conservative view of human nature hindered U.S. relations with the Muslim world by focusing too much on military interventions, counterterrorism measures, and coercive interrogation techniques. More than right-wing Americans, Obama assumed that human nature is cooperative—even across cultures. Thus, reaching out to Islamic countries was Obama’s top foreign-policy priority.

On the very first day of his presidency, Obama called the leaders of the Palestinian Authority, Jordan, and Egypt. He also called Israeli prime minister Ehud Olmert to request that Israel cooperatively open its borders with the Gaza Strip (even though Gaza was under the administration of Hamas, which both the Israeli and U.S. governments considered a terrorist organization). Obama then announced the appointment of a special envoy to promote a US-brokered peace process in the Middle East (a move that President Bush had resisted).

Obama granted his first interview as president to the Arab cable TV network Al Arabiya. One of his first foreign trips was to Turkey and Egypt. At Cairo University, in the heart of the Arab world, the newly elected liberal president reached out to Muslims, offering them “a new beginning” based on “mutual interest and mutual respect.” During his presidency, Obama would prohibit torture and ban the phrase “war on terror” from official government discourse. Underlying these policy shifts was an assumption that Muslim societies had a predominantly cooperative nature—as long as the United States shifted its approach to them in a more egalitarian direction.

Differing perceptions of human nature may divide the left from the right on economic issues as well. Evolutionary economist Paul H. Rubin of Emory University has suggested that “preferences regarding altruism” translate into different fiscal policies. Rubin means that liberals (who perceive human nature as more cooperative) favor greater income redistribution than conservatives (who seek to reduce taxes).

To the extent that people identify free-market capitalism with self-interest, capitalism has polarized the political spectrum. The far left has decried self-interested capitalism as the root of all evil, and accused the right of celebrating self-interest by worshiping the god of free markets. The far right, on the other hand, has denounced socialist control economies for impeding the pursuit of competition and sapping away motivation.

Belief in a Dangerous World

If, as conservatives tend to believe, human nature is fundamentally competitive and self-interest prevails, then people live in a dangerous world. The “dangerous world” metaphor has long been associated with right-wing ideological views. In the last couple of centuries, though, this metaphor has taken the form of folk-Darwinism. University of Michigan philosopher Peter Railton has dubbed this worldview “your great-grandfather’s Social Darwinism,” in which “all creatures great and small [are] pitted against one another in a life-or-death struggle to survive and reproduce.”

In fact, folk-Darwinism’s ruthless “survival of the fittest” concept is a one-sided (and frequently distorted) view of the fuller scientific picture of evolution that has developed over the second half of the twentieth century. Since the 1960s, biologists have made major advances in understanding how evolution motivates various kinds of altruistic cooperation in nature—in addition to self-interest (which we’ll learn about in part VI). Nonetheless, public opinion’s idea of folk-Darwinism, which situates people in a dangerous jungle world, has generally been evoked to support a right-wing moral philosophy.

Numerous political psychologists have commented on the right’s “Darwinian” dangerous-world metaphor. The Authoritarian Personality group at UC Berkeley remarked how highly ethnocentric subjects had “a conception of a dangerous and hostile world” that resembled an “oversimplified survival-of-the-fittest idea.” One conservative subject recalled the discipline that he used to receive from his father: “I always accused him of being harsh. . . . And apparently this all falls in with Darwin’s theory too.” Others who have linked folk-Darwinism’s dangerous-world motif to conservatism include the British psychiatrist Roger Money-Kyrle (1951), Princeton political psychologist Fred Greenstein (1975), and Berkeley metaphor theorist George Lakoff (2002).

The social-Darwinist survival-of-the-fittest idea appears most obviously and prevalently in the discourse of the extreme right. Adolf Hitler saw life as a zero-sum struggle between the races, in which one group would always seek to dominate the other. In a 1928 speech that Hitler gave in Kulmbach, Bavaria, he envisioned a conflict between races in pseudo-Darwinian terms:

The idea of struggle is as old as life itself, for life is only preserved because other living things perish through struggle . . . in the struggle, the stronger, more able, win, while the less able, the weak, lose . . . it is not by the principles of humanity that man lives or is able to preserve himself above the animal world, but solely by the means of the most brutal struggle.

Hitler erred by confusing strength and animal brutality with fitness. He overlooked how cooperative behavior in human and nonhuman animals plays a major role in contributing to fitness, including the struggle for survival. Moreover, the inhuman acts committed by humans in the name of Hitlerism greatly surpassed the brutality of any other known animal. Nonetheless, Hitler viewed the world as extremely dangerous, and he attributed the danger to a misconstrued social Darwinism.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, ethnographer Raphael Ezekiel discovered the same, naturalistic dangerous-world metaphors among extreme right-wing groups in the United States. Richard Butler, the leader of the Aryan Nations, used animals to describe his political convictions:

Of course, we know the jungle, that the lion will eat the rabbit, and a rabbit doesn’t have any right. He doesn’t have any right to life, he has a right to use the endowments that nature and the genetic program have, to save his life. In other words, to run down the hole when he sees something [stronger] coming after him, a coyote or something.

Tom Metzger, the leader of White Aryan Resistance, expressed a perception of human nature in which competition is taken to the extreme. Metzger believed that little had changed since Hobbes’s state of nature, since life remained a war pitting man against man: “either I am strong enough to defeat you or you will smash me. It’s simple,” he said.

Ezekiel uncovered a similarly dangerous worldview among a Detroit cell of neo-Nazis. What most impressed the ethnographer about the neo-Nazis after his months of fieldwork with them was the emotion of fear: “These were people,” he explained, “who at a deep level felt terror that they were about to be extinguished. They felt that their lives may disappear at any moment.”

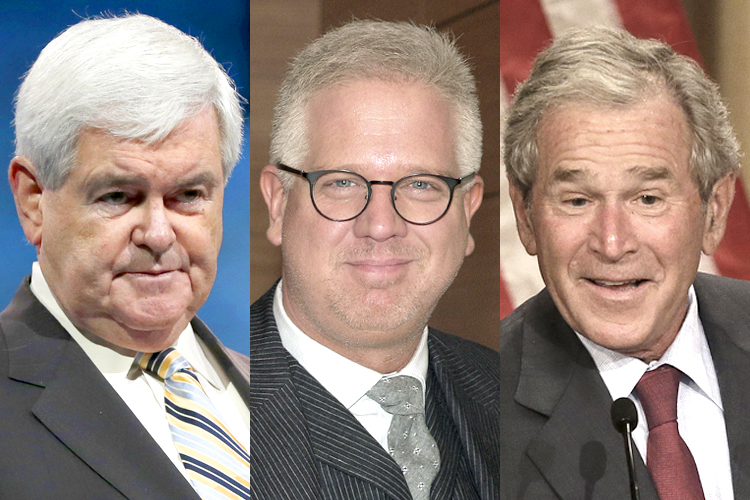

A palpable fear of a dangerous world figures prominently even in the mainstream American far right. Glenn Beck, the Tea Party–aligned public-opinion leader, feels that people are out to get him. Beck wears bulletproof vests when speaking in public. He also planned to build a six-foot barrier around his home in New Canaan, Connecticut, to barricade his residence against bullets (but the security wall conflicted with local zoning ordinances).

Beyond these individual cases of political leaders, is there any hard proof that right-wingers in general fear a dangerous world any more than run-of-the-mill liberals do? Beyond conventional questionnaires, innovative lab research has shed important light on this human-nature problem. University of New Mexico psychologist Jacob Vigil used computers to alter photographs of human faces; he simplified the photographs into “sketches,” and then blurred them to create emotionally ambiguous expressions. Next, Vigil had 740 adults interpret the emotions on the faces. Republicans were significantly more likely than Democrats to see threatening or dominating emotions in the hazy faces (other factors such as gender, age, and employment status, however, did not affect their perceptions).

Thanks to independent experiments later conducted at the University of Nebraska, we now know that as people process these facial emotions, there are also differences in brain activity between liberals and conservatives. Compared with liberals, conservatives process dominant emotions (like anger and disgust) more quickly. Karl Evan Giuseffi and John Hibbing discovered this curious physiological trend by using electroencephalograms to measure electrical activity in the brains of people as they viewed dominant and neutral facial expressions. Because the brain’s electrical response to these faces occurs within a third of a second, these rapid, ideologically important reactions appear to take place at an unconscious level of awareness.

Is there any other way to objectively determine whether conservatives truly fear a dangerous world more than liberals? Political scientists and psychologists from Rice University and the Universities of Nebraska and Illinois came up with a creative experiment to answer this question beyond a reasonable doubt.

The researchers showed a series of thirty-three images to a group of adults with strong political beliefs. Three of the pictures depicted threatening conditions: the first had a very large spider on the face of a frightened person; a second image showed a dazed individual with a bloody face; and the third one showed an open wound with maggots in it. In a control condition, the psychologists replaced the three startling pictures with nonthreatening ones (a bunny, a bowl of fruit, and a happy child).

While the subjects viewed the images, the scientists monitored their skin conductance to measure fear (arousal causes tiny amounts of perspiration, which alter how well electricity flows across the body’s surface).

The research team discovered that the individuals who had a higher physiological response to the threatening images (i.e., the people who were more startled and therefore sweat more) were significantly more likely to have conservative attitudes. For instance, they tended to support capital punishment, patriotism, and the Iraq War. Those who were less startled by the threatening images generally supported pacifism, foreign aid, and liberal immigration policies. Physiological responses to bunny rabbits and bowls of fruit, of course, did not predict political orientation.

This dangerous-world experiment is particularly valuable because it is quite clear what causes what. If an MRI scan reveals differences between the brains of liberals and conservatives, we cannot be sure whether nature or nurture is ultimately responsible. Brain differences could be innate or environmentally acquired or both. But the physiological fear responses in this “spider” experiment depend on sweat; and the sweat glands are controlled by the sympathetic nervous system, which is involuntary. It’s highly unlikely that sweating in response to a spider depends on the environment in which a subject was nurtured (especially if the subjects are from the same location) and that the conservatives happened to have more traumatic spider experiences than the liberals.

Beyond introspective surveys and subjective ratings of facial emotions, then, it seems as though conservatives truly do perceive the world to be a more dangerous place than liberals do—even while asleep. Research on the dream lives of Americans found that Republicans reported nearly three times as many nightmares as Democrats. Conservatives were also more likely to initiate physical aggression in their dreams, and they were twice as likely as liberals to dream about male characters. Left-leaning dreamers, in contrast, reported more female characters in their dreams.

Belief in a Degenerating World

In addition to believing in a competitive human nature and a dangerous world, right-wingers are also more likely to perceive that the world and its morality are increasingly degenerating. The term “conservatives” itself implies a desire to keep what is good and prevent it from deteriorating into something worse. The political left, in contrast, is more prone to thinking that human nature can evolve into something better. The term “progressives” implies this belief that the advancement of morality is possible and desirable.

The sensation of deteriorating social morality is not merely an artifact of the modern Western world; people in ancient Greece, Israel, China, Rome, and nineteenth-century Europe have expressed similar concerns, according to the research of social psychologist Richard Eibach. Likewise, many Americans commonly point to a perceived rise in teenage pregnancy as proof of moral decay. A 2003 poll revealed that 68 percent of adults thought teen pregnancy was on the rise—even though teen births had fallen by 31 percent over the last decade.

The likelihood of holding a “degenerating world” perspective, however, depends significantly on one’s political orientation. The 2000 National Election Study asked Americans whether they thought that “newer lifestyles are contributing to the breakdown of our society.” Fully 80 percent of conservatives agreed with this statement, compared with 59 percent of moderates, and 49 percent of liberals.

The RWA test takes advantage of this relationship to measure political orientation. The scale’s content within the “human nature” category heavily pertains to the “degenerating world” theme. Conservatives are more likely to agree with RWA items that include the following phrases:

* “The way things are going in this country, it’s going to take a lot of ‘strong medicine’ to straighten out the troublemakers, criminals, and perverts.”

* “. . . the rot that is poisoning our country from within.”

* “The facts on crime . . . and the recent public disorders all show we have to crack down harder on deviant groups and troublemakers if we’re going to save our moral standards. . .”

* “In these troubled times . . .”

Each of these phrases suggests a society in the process of moral decay. They express the sensation not only that human nature is bad, but also that it’s growing even worse.

It’s quite easy to find “reactionary” politicians on the right of the political spectrum who believe that the present and future are decadent eras, and who yearn to return to a past that they believe was more moral. Newt Gingrich is one of them. Gingrich served as a Republican congressman from the conservative U.S. state of Georgia for twenty years. In March 2011, he announced his bid to run for president on the Republican ticket. In Gingrich’s worldview, the moral fabric of America is increasingly deteriorating. He has especially expressed this “degenerating world” opinion during the administrations of liberal presidents.

In 1995, Gingrich had just become speaker of the House of Representatives, to lead his party in opposition to Bill Clinton. Gingrich claimed: “We had long periods in American history where people didn’t get raped, people didn’t get murdered, people weren’t mugged routinely.” Fifteen years later, in 2010, Gingrich published a book titled “To Save America.” It argued that the values of the United States’ founding fathers were quickly slipping away. America’s morality was under dire threat, Gingrich argued, from President Obama’s “secular-socialist machine.”

Further to the right, the “degenerating world” theme grows even stronger. Commentators have described Glenn Beck’s television program as having an ethos of “extreme doom and pessimism.” Even an anchor from Beck’s own conservative outlet, the Fox News Channel, called Beck’s show “the Fear Chamber.”

On the extreme right end of the spectrum, people’s assessment and prognosis of human nature becomes the gloomiest. A Detroit neo-Nazi interviewed by Ezekiel offered his thoughts on the subject: “People are getting worse and worse and worse . . . and murder and torture and all this. Just for the sake of laughing and enjoying it.”

If conservatives fear that human morality is deteriorating, then the political left is well known for its hope that human nature will improve. Before he became a liberal president, Barack Obama gained his country’s attention by publishing a book called “The Audacity of Hope” (2006). During his Nobel Peace Prize lecture at the end of 2009, the progressive president touched on his theory of human nature: “we do not have to think that human nature is perfect for us to still believe that the human condition can be perfected,” Obama said. Not “improved,” but “perfected”—the same term that Rousseau used.

From “Our Political Nature: The Evolutionary Origins of What Divides Us,” by Avi Tuschman (Prometheus Books, 2013). Reprinted by permission of the publisher.