IN MY LAST SEMESTER of college, I found myself inexplicably drawn to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Not to any one congregation or adherent, but to the Church itself, and to its holy text, theBook of Mormon. I can’t pinpoint the source of my fixation any more precisely than to say that at some point in early 2007 I learned about the LDS belief in the eternal family, which holds that marriages sealed in the temple continue in the afterlife, uniting parents and children forever. My inspiration was quite possibly HBO’s massive marketing campaign for Big Love, which dominated my corner of the East Village that spring. Doctrinally assured reunion in heaven appealed intimately to me, the melancholy culturally Catholic but functionally agnostic child of lapsed Catholics. At 22 years old, I constantly missed my parents (alive and well but several states away) and the happy childhood over which they had presided. No one else seemed to suffer from the pervasive nostalgia I had begun to accept as inescapable.

IN MY LAST SEMESTER of college, I found myself inexplicably drawn to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Not to any one congregation or adherent, but to the Church itself, and to its holy text, theBook of Mormon. I can’t pinpoint the source of my fixation any more precisely than to say that at some point in early 2007 I learned about the LDS belief in the eternal family, which holds that marriages sealed in the temple continue in the afterlife, uniting parents and children forever. My inspiration was quite possibly HBO’s massive marketing campaign for Big Love, which dominated my corner of the East Village that spring. Doctrinally assured reunion in heaven appealed intimately to me, the melancholy culturally Catholic but functionally agnostic child of lapsed Catholics. At 22 years old, I constantly missed my parents (alive and well but several states away) and the happy childhood over which they had presided. No one else seemed to suffer from the pervasive nostalgia I had begun to accept as inescapable.

“As moderns, we are born into a tradition of disbelief,” writes Patricia Hampl. “The life of the spirit is not an assumption. It is a struggle. And the proof of its existence for a modern is not faith, but longing.” My struggle was against logic, against the happily atheist peers aghast at my inclinations, against my own frantic attempts at adulthood. Religious longing didn’t have a place in my universe. I have been since childhood a secular humanist through and through, the kind of pain in the ass kid who liked to deconstruct contradictions between the Old and New Testaments to bother my CCD (Confraternity of Christian Doctrine) teachers. In fifth grade, I refused to begin the sacrament of confession (rebranded “Reconciliation” in a 1990s attempt at a kinder, friendlier Catholicism) because, as I patiently explained to the adults, I had no crimes to confess. I had done nothing wrong: I was 10 years old. My parents, wary of the iron-fisted morality that had warped their own upbringings, did not force the issue.

I couldn’t articulate it then, but what I was rejecting was the habit of self-incrimination, of shame and self-punishment. I would not police my inner life. (I did finally go to confession in the seventh grade, at the urging of a CCD teacher who had converted from Judaism; the fact that she had chosen her faith rather than blindly followed it appealed to me. I told the priest I was mean to my sister sometimes, hoping for penance on the rosary. He told me to “think about it.”) My parents taught me against the retrograde politics of Catholicism, even as they tried valiantly to initiate me into the mysticism of possibility that they believed the Church to represent. Before puberty I knew that homosexuality was no sin, that the Bible was simply a beautifully written book of some good ideas, and that a woman’s sovereignty over her body was absolute, even divinely ordained. I understood the symbiosis between faith and power, and learned not to take proscriptions too seriously.

Yet even as I skirted religion’s pitfalls, I continued to yearn for both its rigor as well as its access to the divine. I devoured mythologies — Greek, Roman, Norse, Celtic — and carried totems. Determined to find real magic, like so many bookish suburbanites before me, I tried Wicca, sending away to Vermont for wands and constructing an altar of heirlooms in my bedroom. The candle smoke stains on my childhood bedroom’s flowered wallpaper have long outlasted my commitment to polytheism, of which traces remain only in the syncretic prayer I involuntarily whisper in bad times. It begins “Hail Mary, Mother of God, Blessed art thou amongst women” and ends “Blessed be and let it harm none.” Even into adulthood, glimpses of Catholic Nuns and Buddhist monks in habit made me smile. Mass, and the veneration of the idols at Hindu temples alike filled me with something I privately called “the Cathedral feeling.” I wanted a guide to my own world of sprits, even as I understood that such a thing was impossible, that the very composition of my interior world precluded it. And then I found myself drawn to LDS with an interest so intimate, so painful, that I couldn’t even consider its source without crying.

I read everything I could about the Church, and finally, one Sunday in February, I attended services at the Union Square First Ward. I was received warmly and without reservation, despite the fact that I had shown up to the early meeting for families instead of the later one for single people. I stayed for both. The people I met that day were unfailingly kind and generous, and my father’s advance warning to “be careful” seemed preposterous. But even in my excited state I avoided the missionaries. Unlike many of my classmates, I took no pleasure in forcing an argument with a religious person on a dramatic social-issues topic (Abortion! Gay marriage! Women priests!), perhaps because I had always been so rigidly polite that it was difficult for me to correct the misspelling of my own name. From my reading I knew that if I spoke to the missionaries, they would want to visit me at home to continue the conversation. And as intrigued as I was by LDS, I couldn’t think of anything more awkward than entertaining two earnest young men in the one-bedroom efficiency I shared with my boyfriend and male best friend, a bad situation that would be made worse by the uneasy knowledge that we and the elders were all around the same age. When, several weeks prior, I’d ordered my free copy of the Book of Mormon, whose delivery virtually guaranteed a missionary visit, I had it delivered to my childhood home. (I figured my mother could handle it: back in the 1970s, a pair of missionaries sent to her by a converted friend visited weekly for six months. Rather than send them away, she served them lemonade in her living room, passing week after week of pleasant hours, until they finally gave up.)

As positive as that experience was in many ways, I did not continue my relationship with LDS. Yet even after I found that I fundamentally could not believe in many of the Church’s doctrines, I couldn’t shake my connection with a particular verse from the Book of Mormon, which promises that the challenge of faith is its guarantee:

But behold, if ye will awake and arouse your faculties, even to an experiment upon my words, and exercise a particle of faith, yea, even if ye can no more than desire to believe, let this desire work in you, even until ye believe in a manner that ye can give place for a portion of my words.

For a long time, I kept these words pinned up above my desk, trying to divine what, exactly, moved me so deeply. I would not be a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, no matter how many episodes of Big Love left me misty and longing.

¤

The canon of literature about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is slim. Books about Mormonism fall overwhelmingly into one of two pulpy categories: evangelical Christian conversion narratives, lurid exposés like Jon Krakauer’s Under the Banner of Heaven, Martha Beck’s Leaving the Saints, and the endless ghostwritten memoirs of escapees from polygamist compounds. Barring inspirational literature, there are few Mormon novels worth remarking: Halldór Laxness’sParadísarheimt (Paradise Reclaimed), the indelible fiction of Judith Freeman, and Walter Kirn’s Thumbsucker, in which an adrift teen careens through an Adderall prescription and an unhappy sexual awakening before finding something like balance via his family’s conversion to LDS. Kirn gets at a bit of the masculine anger inside the young Mormon man — the sense of being somehow neutered, and yet umbilically attached to the Church, not to mention convinced separation from it guarantees one’s downfall. But Thumbsucker is a comic novel, and it ends with the narrator’s departure for New York City and thus the promise of secular resolution. Mormonism lacked a novel of the disaffected, the suffering and rage of the deserting and deserted — and because I couldn’t read this story, and because it was not my own, I got how little I understood: my latter Latter-day revelation.

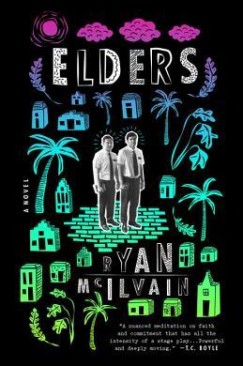

Ryan McIlvain’s Elders, published this year by Hogarth, finally fills this gap. Inlaid with darkness and violence, it is the story of disaffected young men’s machinations towards adulthood through the apparatus of the Church. Set in the invented Brazilian city Carinha, “a world at the bottom of the world,” in the tempestuous months surrounding the March 2003 US invasion of Iraq, Elders presents two protagonists in conflict: the devout Brazilian Elder Passos and the doubting American Elder McLeod, who narrate alternating chapters. They share in common a certain intransigent personality — sympathetic, frustrating, endearingly young, and irritatingly stubborn — and a peculiar brand of homesickness, in which longing for home conceals an existential desire for self-knowledge. Neither sheltered young man possesses the insight nor the bravery to recognize their particular brand of weltschmerz, however; to do so would constitute heresy. So Passos and McLeod labor together at the punishing task of “tracting,” roaming the residential neighborhoods of Carinha in search of souls to save. In their youthful idealism, Passos and McLeod are familiar figures, and I hoped against hope that the elders would peaceably resolve the issues between them and their Church. This was a selfish desire, a wish to see LDS as still fundamentally good, or honest, or both; they are not the same thing. But McIlvain is too clear-eyed to give me my happy ending.

For all my previous reading, Elders washed me in new vocabulary; in addition to “tracting,” I learned about “P-Day,” Preparation Day, the missionaries’ weekly day of rest, on which they are allowed to write letters and attend to household matters. “Transfers” are the intermittent personnel reorganizations that redistribute the missionaries to different wards and new companions; “senior companion” and “junior companion” are the titles that indicate how the intricate LDS hierarchy extends to even the relationship between paired missionaries. “Golden” is the missionaries’ keyword for an especially receptive potential convert, someone primed to accept their testimony.

Passos is the senior companion in his pairing with McLeod, who remains junior 18 months into his two-year stint. Born into urban poverty in northern Brazil and baptized as a teenager, Passos studies English tirelessly, eager to become an assistant to the mission president, a position which he hopes will lead in turn to a scholarship to Brigham Young University. At first, his project seems to be the economic and spiritual uplift of his younger brothers and grandmother. But this respectable aim masks agonizing grief: like me, Passos is preoccupied with the promise of eternal family, motivated by a desire to reclaim his lost mother, who died of cancer one month before his first encounter with the Church. Although his faith is perfect, his aim is off; the eternal family does not entail, as my husband has reminded me, “just hanging out with your mom forever.” It is more complicated than that, and less easily grasped.

McLeod (his first name is Seth, and Passos’s is Cristiano, but the enforced formality between the two missionaries means that these names appear so infrequently as to be meaningless) hails from the suburbs of Boston. His difficulty with belief is not new; in high school, he rebels against the mores of his faith, shrieking at a devout girlfriend, “Look! I’m 18 years old! We are 18 years old! We should be fucking right now! We should be clawing at each other! What is wrong with us?” (He is probably more like I would have been, if I had been raised Mormon.) McLeod’s mission is an attempt to make amends to his religious family — McLeod pere is a bishop in the Church — for his heretical outbursts. Despite his struggle to believe, he sees himself as pure of heart, refusing to play the “game” of mission politics after a year of intense scriptural study fails to shore up his lagging faith. McLeod is a neophyte intellectual in elder’s clothing, a young man better suited to life as an incorrigible know-it-all in a freshman writing class, who longs to “take history and literature classes and study facts, or study fiction, and put behind him this muddy slosh of the two.”

In the first chapter, a line of poetry is stuck in McLeod’s head: “who loves me must have a touch of earth / the low sun makes the color.” He is frustrated to be unable to recall the attribution (it’s from Tennyson’s Idylls of the King). The touch of earth is what McLeod hopes to find in Passos, to whom he has been newly assigned, his companion in a world stripped of dirt and ambiguity: just a bit of grounding and grit. A lesser writer would present this as an innocent desire, unconnected to the implicit power imbalance between the American McLeod and the Brazilian Passos, both of who come to epitomize their national identities. But Elders is sharply focused on the broader issues at play in the missionaries’ relationship: Church and government corruption, postcolonial identity, and class struggle are all given voice here. By book’s end, the conflict between the United States and the rest of the world comes to overshadow the struggle between belief and doubt. McLeod is constantly taunted by Brazilians protesting the Bush Administration’s unilateralism, first by strangers on the street, then by his acquaintances, and finally by friends, a refrain that Passos crushingly takes up as well. Reading, I felt my own complicity, the way my exoticization of LDS allowed me to overlook its brutality, its failures of conscious, its imperialism.

A curious narrative disjuncture persists between the two protagonists. McLeod’s interiority is pervasive, influential even in the sections narrated by Passos. His voice and perspective flickers piecemeal in every scene, whereas the Brazilian missionary seems simultaneously more fully realized — more complete — and more fictional. The easy way to read this aesthetic quirk would be to assess Elders as a roman à clef, with McLeod as McIlvain’s stand-in, and perhaps there’s some of that here. My theory is simpler: Passos’s fervent belief is a foreign country to reader and author both, in order to evoke this strange land, McIlvain must map it. McLeod’s inveterate skepticism is more intimate, more deeply felt, and thus often more palatable than Passos’s zeal. McIlvain combats this likability problem by dosing the reader with intoxicating personal tidbits about the Brazilian elder throughout, as in this description of how Passos’s charismatic Catholic upbringing informs his missionary work:

Passos felt the spirit building in him, a different energy, and he began to lift — he did it unconsciously — into the familiar registers of the charism priests of his youth, their rhythms, their bouncing cadences. This music rose in Passos at moments of excitement, heat — it rose alongside their excitement, like a bright shirt bleeding freer as the wash water warms.

McIlvain’s delicate handling of Passos imbues the missionary’s words with great power; when he says, “I testify of this power […] I know it is real, very real,” who would argue? The author gives us glancing visits to Passos’s inner life, unfolding his secrets slowly. When, in the novel’s last pages, we are granted access to Passos’s tender dream of his lost mother, the scene packs the gutting power of a final refrain. I know that I am more like McLeod, if only for my skepticism and bookishness; but if my longing, guilty id were given voice and body, it would not look unlike Passos, eating fruit with his mother in the garden of the self.

Passos and McLeod build a tentative friendship, coaxing each other out through a series of freighted discussions. Then they meet Josefina, a woman willing to listen, “golden” through and through. At first, the elders are relieved and happy; a convert is rare for any missionary, especially in a country as deeply Catholic as Brazil. But Josefina’s conversion is fraught from the start, assailed by both her husband Leandro, who is suspicious of the Church and the young men bearing its message, and the sexual tension that develops between Josefina and McLeod. Rather than entrapping the characters in a love triangle (or quadrangle, depending on your reading of Passos), McIlvain describes how Josefina, as the only woman with whom the elders are allowed to spend time, is made an automatic object of desire:

Josefina came to the door in a white flowing blouse and black pants, both modest, her hair done up in a bun. Her look fell closer to the formality of her Sunday dress than the casualness of her usual attire. Why the change? McLeod wondered — worried. Has she seen me…seeing? Is that the reason for her modesty?

Everything about Josefina is forbidden and eroticized, from the décolletage exposed when “her blouse dipped open, revealing brown, secret skin,” to the “catlike” act of carrying a bag of chips in her mouth because her hands are full. Her openness to the Church makes Josefina vulnerable to the tempestuous relationship between McLeod and Passos, but she is not an actor here, only a catalyst. If there is a love story in Elders, it is between the two missionaries, who in the novel’s first half develop a lovely, easy intimacy, tutoring each other in their native tongues and fantasizing about a continued friendship in the United States. When Passos and McLeod exchange books as a sign of friendship, the Brazilian gifts the American an advanced guide to Portuguese grammar, while McLeod gifts Passos that stalwart of high school valedictory speechwriting, Dr. Seuss’s Oh, The Places You’ll Go! The disconnect is made all the more painful when these gifts are divested as part of an argument over a third text, the Dictionary of Mormon Arcana that McLeod continues to consult, over the protestations of his father and Passos, in a frantic search for knowledge. In Elders, the written word is sacred, scarce, and incendiary — like Josefina, an object of desire imbued with the destructive power of creativity. Both men hunger for truth and seek it in books, but the stakes and qualities of their seeking are wildly divergent.

Their interactions with Josefina and Leandro slowly dissemble into chaos and confusion. Despite the souring of their initial infatuation, McLeod and Passos work together for Josefina’s baptism, even after it becomes clear that Leandro is a lost cause. When administrative interference prevents this event via a change of conversion protocol that demonstrates, once again, deference to hegemonic forces, the Church is revealed as the ax that cleaves McLeod and Passos. Josefina cannot convert without her husband; the Church has moved to focus solely on whole-family conversions. This could be read as a critique of the Church’s inherent sexism, and it is that; but what infuriates McLeod, and, one senses, McIlvain, and me, is the illogic. Josefina is golden, wants to convert, but the Church doesn’t love her back. The men are thrust back into their intensely personal interior worlds, giving the book’s denouement the hallucinatory power of a fever dream.

The missionaries face their last trials as individuals. Elder McLeod’s a visit to a whorehouse is rendered in such stomach-churning detail that I was almost relieved when McLeod vomits from anxiety and moral terror; I wanted pleasure for him, a lascivious realization, but the prostitute’s body contains only bottomless loss for the missionary. She is the hole he must climb through to escape himself. Facing with his true nature, McLeod experiences not the mythologized relief promised by the modernist epiphany, but a storm of loneliness so powerful that it threatens to destroy him. My one complaint while reading Elders is its dim colors, the relative ugliness of McLeod and Passos’s world, where every place — Brazil, Boston, Utah — seems to be one gray drag. Of course I wanted beauty. I always want beauty, even where it doesn’t belong.

Meanwhile, Elder Passos delivers a sermon while seemingly every Brazilian, including members of his congregation who have secreted radios, tensely follows the soccer game that will decide the Latin American Championship, an archly secular event that carries greater spiritual heft than the elders’ testimonies. Passos presses onward in a room riddled with concealed radios, becoming a kind of athlete of faith, a sacrificial figure bearing his testimony onwards, further. At the end, I knew McLeod would return to the United States; Passos’s destiny was less clear. It was easy to imagine him going on like that, railing and dreaming to a disinterested crowd forever.

Was I ever golden? Maybe. In the moments before the first inarticulate testimony at the Union Square First Ward, when I sat in the clean white pew beside a fresh-scrubbed family, receiving friendly congregant after friendly congregant, and thumbed through the gold-edged Book of Mormon, it seemed possible. Now, after all my research and seeking, it is impossible. Knowledge took this faith away from me, too, as perhaps it will all of them, until I am back to square one, lighting candles on a little table in my bedroom and mixing up prayers like tonics against disease.

My favorite verse from the Book of Alma — “experiment upon my words, and exercise a particle of faith” — is the animating principal of Elders, haunting both McLeod and Passos, taunting them to continue their exhausting quest, an indelibly American idea: try it and see, give it a go, try your hardest and see if you don’t win. This challenge is not only dangerous, McIlvain shows; it is also cruel. Life offers few sure bets. If we must experiment on faith, we must also understand that the experiment is the leap itself.

I thought that this passage from the Book of Alma was unique to LDS, which was what so beguiled me; the idea that this uniquely American religion promised to reward experimentation. But I have found its echo in a most un-Mormon source, the letters of Flannery O’Connor, who in 1955 wrote to her friend Elizabeth Hester:

What one has a born Catholic is something given and accepted before it is experienced. I am only slowly coming to experience things that I have all along accepted. I suppose the fullest writing comes from what has been accepted and experienced both and that I have just not got that far yet all the time. Conviction without experience makes for harshness.

Conviction without experience is what haunts McLeod and Passos, and what has haunted me, too. What was I supposed to do with all my belief without something to believe in? All I knew how to do was feel guilty, and want, and mumble-pray for things to be okay. I don’t know if things are going to be okay, but I know they are going to go. And maybe, like O’Connor, I can claim my Catholic birthright as something given and accepted.

¤

I see pairs of elders everywhere. In Prague, they were fellow passengers on a tram, whom I watched disembark in a residential neighborhood and set out on the Work. In Copenhagen they were expert bicyclists, cannily navigating the traffic-choked intersections near Rådhuspladsen. A few weeks ago I saw them at the Los Feliz Post Office, wearing Spanish nametags and taping shut a small cardboard box.

Last year I went for the first time to Salt Lake City, where I was excited to see the many Church historical sites and museums. I toured Lion House and the Assembly, heard an organ concert at the Tabernacle, and admired the newlyweds taking photographs in front of the Temple. But by the end of the day I had had enough of missionaries, of their openhearted desire to bring me into their faith. No matter how many times I explained my respect for the church or demonstrated my knowledge of the Book of Mormon, even quoted it from memory, they still kept trying to tell me that I didn’t know my own story, that their testimony was more meaningful than my own. I envied them their conviction. I pitied them their innocence.

¤