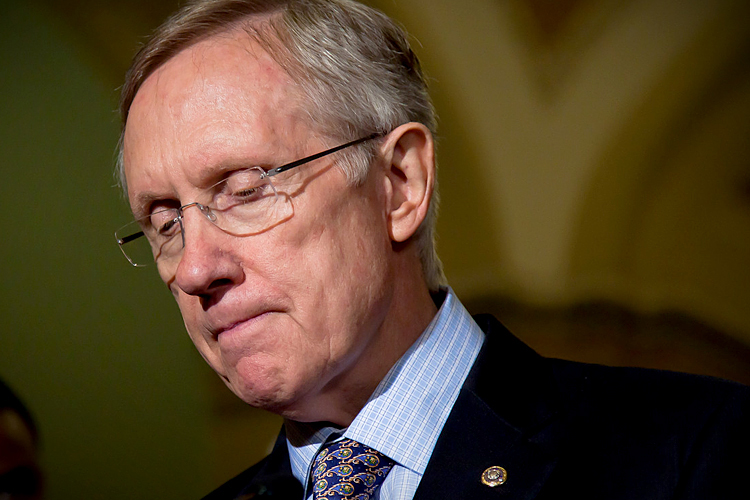

In July of this year, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid used the threat of the “nuclear option” to get a raft of President Obama’s key nominees confirmed, despite persistent Republican threats not to allow it.

Those threats began during Obama’s first term (seriously, that long ago) and several Republicans felt that in the wake of his victory, Democrats would be within their rights to circumvent GOP efforts to nullify the election results by changing the Senate’s filibuster rules.

Instead of allowing the confrontation to escalate, and putting their influence over the confirmation process at risk, a minority of Senate Republicans broke with party leadership to break these filibusters, and allow the nominees to be confirmed the traditional way.

It was a big victory for Reid and the Democrats, but they made a minor tactical error, which they need to correct now that Republicans are at it again. It’s time for Reid to cast his filibuster reform threat the right way.

First, let me stipulate that I believe the Senate rules give the minority way too much power, not just over nominations, but over legislation as well. I think Democrats made an error in 2005 by “capitulating,” instead of allowing Republicans to go nuclear over President Bush’s judicial nominees. And whatever dilatory mechanisms senators want to erect to prevent the Senate from becoming too much like the House, the supermajority cloture era is anti-democratic and unsustainable in a polarized system like ours.

But if we’re playing a game without trump cards, the nuclear option threat can be effective if used wisely and sparingly.

Where Reid went wrong was confining his threat to eliminate the filibuster to executive branch nominees only, implicitly assenting to ongoing GOP obstruction of Obama’s judicial nominees.

The logic is straightforward enough. The term-limited nature of the presidency means executive branch nominees can’t serve for more than eight years. The vast majority serve much fewer than eight. These are temporary positions because the presidency is temporary and with rare exception presidents should be allowed to run the executive branch with the help of people they trust for as long as they’re in office.

Federal judgeships, by contrast, are lifetime appointments. At the appellate level they often shape policy for years and years after the presidents who appointed them have been defeated or term limited out of office. Within the confines of a supermajority cloture system, a Senate minority has a greater logical claim to veto power over these lifetime servants than to veto power over executive branch managers.

But the trick Senate Republicans are playing this year — the power they’re exerting over both the executive and the judiciary — is new, and disjoined from the question of whether individual nominees deserve to serve in either branch of government. They’re denying (or threatening to deny) confirmation to any nominees in order to nullify laws, stymie legitimate policymaking, and “reverse court pack” — keep liberal judges off of one key appellate court in order to preserve its conservative balance for as long as possible.

As such Reid’s distinction between executive and judicial nominees is inapt. The proper distinction is between filibusters designed to serve some legitimate legislative purpose (Rand Paul’s filibuster of John Brennan comes to mind) and those designed to usurp established presidential powers.

Reid’s nuclear option threat earlier this year was effective and badly needed. It culminated in the confirmations of Consumer Financial Protection Bureau director Richard Cordray, Labor Secretary Tom Perez, and a full complement of National Labor Relations Board members, among others. Without a director, the CFPB loses a great deal of regulatory power. Without a quorum the NLRB can’t function at all.

But the principle Reid established is that members of the Senate minority should not be allowed to block otherwise uncontroversial executive branch nominees in order to impose policy outcomes they’ve been unable to secure via normal electoral and legislative channels.

He inadvertently left the door for Republicans to deploy the same tactic against judicial nominees wide open.

Now, Republicans are refusing to confirm any Obama nominees, no matter how qualified, to fill three vacancies on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. On Thursday, they filibustered Patricia Millett, who even Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, agrees is a qualified jurist, and they’re committed to filibustering two more. They’ve made the embarrassingly lame argument that the court doesn’t need a full complement of judges because it has a light caseload, but had no qualms about filling all but one vacancy on the court under President Bush when it had a lighter caseload, and have no qualms today about confirming judges to the 10th Circuit, which has the lightest caseload in the country.

In reality Republicans are desperate to preserve the court’s conservative balance because it’s the second most powerful court in the country, and the one through which challenges to the Affordable Care Act, climate change, financial reform, labor and other regulations will likely run. If Obama’s nominees are confirmed the chances that a three-judge panel on the court will uphold these regulations will increase dramatically.

In moments of candor some Republicans even cop to it. “We’re worried about that court being a significant bastion for administrative law cases on Obamacare,” Sen. Mark Kirk, R-Ill, told Huffington Post.

Reid, along with Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., have already warned Republicans that they’re igniting another nuclear standoff. The fact that Republicans also filibustered Rep. Mel Watt’s nomination to lead the Federal Housing Finance Agency on Friday further underscores the fact that the advise-and-consent truce has broken down. But to consolidate the support of wary Democrats, Reid should focus less on the individual nominees, per se, and more on the principled line, similar to the one he drew during the debt limit fight, that a minority in the Senate shouldn’t be allowed to use the routine fact of executive and judicial vacancies to essentially make law.

Fortunately for Reid, the Democratic caucus grew by one member (Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J.) on Thursday. That increases his margin of error. If he can convince 49 others to support a rules change in theory, he’ll get these nominees confirmed one way or another.