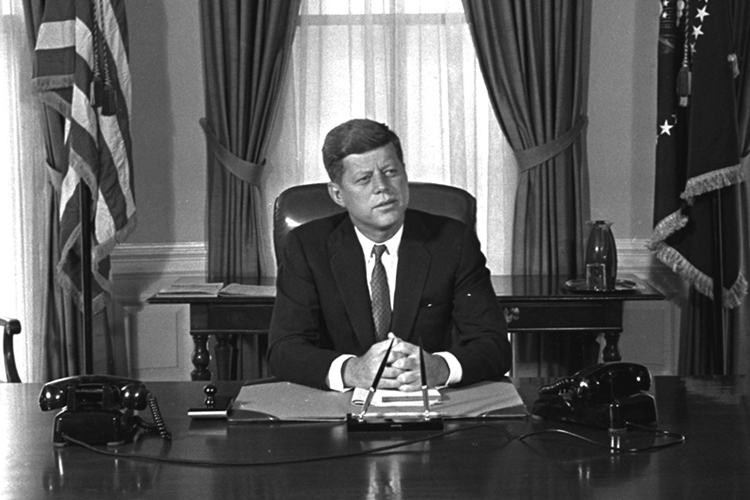

The season of remembering “Camelot” — the presidency of John F. Kennedy — is upon us, as the 50th anniversary of Nov. 22, 1963 approaches. Those 40,000 books already published about JFK are getting new competition in bookstores and online bookselling sites as a plethora of new books examine every aspect of his personal life and his presidency.

While I share a certain admiration for JFK, I’ve been amazed to see the romanticizing of him, his family and his presidency extend even to serious subjects such as the war in Vietnam.

Analysts who write or speak in definite terms about what he would have done regarding the Vietnam problem are in the wildly ironic position of having certitude about something that JFK, himself, found perplexing and without obvious solutions. For close to a decade, the U.S. had tried to save non-communist South Vietnam from the military attacks and political intrigues waged by communist North Vietnam and its South Vietnamese supporters, the Viet Cong.

JFK seems to have said different things to different friends, advisers and staffers in 1963 about what he would do about South Vietnam in the future. In the decades since his death, what has most intrigued some who loved Kennedy but hated the Vietnam War, as it grew and continued under his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, is that JFK told or hinted to a few associates (including antiwar Sen. Mike Mansfield) that he would certainly pull U.S. forces out of South Vietnam, but only after winning reelection in 1964. Mansfield and others who allegedly heard this from Kennedy only revealed those conversations years after his death, when the war had gone long and sour under LBJ’s leadership. But they have been the source for many a speculative article and book claiming that, if only Kennedy had lived, we would have been spared the trauma of Vietnam.

If true, such stories don’t quite make Kennedy look so wonderful as some of his “defenders” seem to think. After all, Americans had been dying in South Vietnam since 1959, during the Eisenhower presidency. Over a hundred of our soldiers died there in 1963. If JFK actually had definitively decided to pull the U.S. out of Vietnam, why wait until after an election still a year off? Do we really think he was that craven a president? I don’t.

Enough with the Camelot-glossed speculations. There are thing we do know about JFK and South Vietnam: First, U.S. troop levels there grew from around 900 to approximately 16,000 during his presidency. Second, while there were contingency plans to get those soldiers out at some point (possibly the end of 1965), the contingency was South Vietnam becoming successful at repelling the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong. That wasn’t happening in the jungles of Vietnam in 1963. Third, there is no record of JFK having expressed a definite post-election withdrawal intention to Vice President Lyndon Johnson, his attorney general brother Robert Kennedy, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, CIA Director John McCone or any other members of his National Security Council.

Much like other presidents before and after him, Kennedy would have liked to get the U.S. out of the Vietnam situation, but only on terms reasonably favorable to the U.S. This is why he was suspicious and hostile toward South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem’s 1963 diplomatic overtures toward North Vietnam’s leader Ho Chi Minh about some kind of reunification of the South and North. Such an event would have been widely viewed as a “loss” for the U.S. in its ongoing competition with the Soviet Union for global influence.

Unlike his skilled behavior during 1962’s Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy was indecisive regarding Vietnam in 1963, and failed to impose a coherent policy on the warring factions of his administration. The path he ultimately chose at the end of October was as big and consequential a foul-up as his failed “Bay of Pigs” intervention in Cuba in the opening months of his presidency. Like Bay of Pigs, it was a covert action — he authorized our ambassador in South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., and CIA leaders there to support South Vietnamese military leaders in overthrowing Diem, a U.S. ally of nine years’ standing.

Diem was murdered on Nov. 1, during the ensuing coup, but it’s clear that this was not something JFK desired. Just listen to his somber voice — “I feel we must bear a good deal of responsibility for it … the way he was killed made it particularly abhorrent” — in recording a memorandum for the record about the coup and murder shortly after those events. It’s widely available online.

The reason why John F. Kennedy, after months of debates, decisions and much indecision, very reluctantly authorized something so utterly distasteful — overthrowing an ally who was a personal acquaintance and fellow Catholic — is clear: He wanted a stronger performance by South Vietnam’s military against the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese. This, he desperately hoped, might be brought about by new leaders of the South Vietnamese government. If that was achieved, Kennedy hoped, then the U.S. might be able to withdraw at some point. It was a hope, though, not a plan.

Ironically, the man whose advice usually carried the greatest clout — Robert Kennedy — did not win the day in warning against the coup, “We’re putting the whole future of the country … in the hands of someone we don’t know very well.” Indeed, the removal of Diem brought about a worse government and far greater instability in South Vietnam. Its military performance suffered badly due to extreme political turmoil from late 1963 through much of 1965.

JFK didn’t live to see this outcome. We all know his successor Lyndon Johnson, who, as vice president, had opposed the coup in White House meetings, decided to escalate the Vietnam War that ended in defeat for the U.S. and cost Johnson his chance at a second term. However, the myriad of mistakes by Johnson from 1963 to 1968 shouldn’t obscure the fact that JFK could have become just as embroiled in the worst foreign policy debacle in U.S. history just as easily as he could have changed course and ended the conflict in his second term.