My reaction to the news that Blockbuster Video was finally giving up the ghost was like my reaction to the death of any long-forgotten celebrity: Wait, I thought they died a long time ago. That I conveniently forgot about the chain’s sad continued existence wasn’t merely about the offense they delivered to independent film and independent businesses; it was about the time I spent working at one when I was 18. I wore the yellow and blue polo, told you there was nothing I could do about your late fees, snapped open countless clamshell cases to check that you’d been kind and remembered to rewind. Mostly, though, I did what I could to be a remarkably shitty employee.

It was 2000. I’d just moved from Colorado to Los Angeles, and I got the job after my roommate and I spent an afternoon walking in and out of all businesses within a 10-mile radius, collecting applications. I even walked into a funeral parlor and asked if they were hiring, figured it would at the very least be an interesting story. This was not, after all, real life; it was a gathering of real-life experiences. The mortician looked at me as if nervous about what sort of puppet show I’d put on with the bodies when no one was looking, and said no, they were not hiring. When I finally got a job at the Blockbuster Video down the street, I quipped that it didn’t seem too different from the funeral parlor: another place to display the embalmed bodies of Hollywood’s dead.

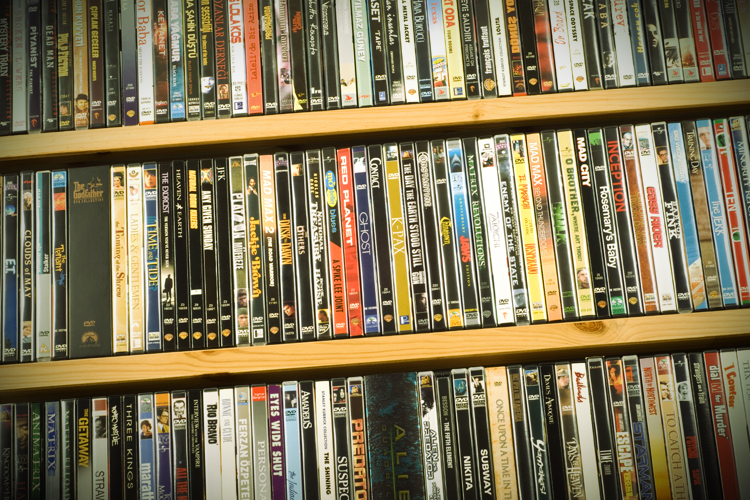

As a proud film buff — the really insufferable kind, masking insecurity with judgment — I was torn. I knew Quentin Tarantino had done his early film scholarship as a video store clerk, and I was busy writing my own script that was a bad rip-off of Jim Jarmusch’s “Down By Law” (which I imagined would also star Tom Waits). But of course Tarantino worked at an independent video store that surely prized some of the more jagged and indigestible cinematic curiosities, the kind of films I was ravenous for, and there were no Jarmusch films at BBV. Instead, as its name suggested, Blockbuster celebrated movies that, like pre-masticated meals, Hollywood fed to audiences mama-bird style. A deeply conservative company, Blockbuster even re-edited the racier films, removing the offensive bits. The version of “American Psycho” they carried seemed so stripped of content that the normal cause and effect of story became almost non-sequitur. And although there can be something oddly wonderful about just how surreal a narrative can get when it’s edited into nonsense, my coworkers and I weren’t afraid to direct customers elsewhere for the uncut stuff, like Kris Kringle in “Miracle on 34th Street”: “You can get deviant sex and chainsaw death at Gimbels!”

Increasingly, we directed people elsewhere because we simply didn’t have the movies they were looking for, despite the computer saying they were in stock. As the store manager put it, “We have a shrinkage problem, and” — with a smirk — “not the ‘Seinfeld’ kind.” As most lost prevention experts will tell you, the problem was internal. I remember going over to my coworker’s apartment late one night. I drank beer and smoked pot with a handful of other employees, both of Blockbuster and the new Virgin Megastore nearby. New to this circle, I was excited for the friendship. We talked about starting a band; they wanted me to play bass, even though I was the only one who hadn’t gauged his ears. In the kitchen, my coworker handed me another beer and said, “So, Kevin, you steal, right?” I looked around: The apartment was furnished more by Blockbuster than by IKEA, and I said, “Yeah, of course.” Everyone was thrilled. Turned out, we’d all secretly been siphoning stock from our evil corporate overlord.

For me, it had begun when a friend who’d worked at another Blockbuster had given me some pointers for the liberation of product. At first, I wasn’t going to do it. I’d never stolen anything in my life, but I was also 18 and eager to push against any form of restraint I encountered, eager to test-drive different selves. So there’d been that first experimental filch, Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Magnolia.” And then, a few weeks later, another. Then another.

Once it was out in the semi-open with my coworkers, we acted like we’d discovered a mutual passion for scrimshaw or falconry, and could now discuss the particulars of the obscure craft with each other. We all had various justifications for stealing — e.g., DVDs were new and we needed to rebuild our collections in the new format, and of course there was the simple fun of it, the thrill of the sport — but the one we really latched on to was that Blockbuster was a large, impersonal, prudish company and we were doing our part to recover personal pride and be the best thorns in the side of the giant that we could.

These were the days when threats to mom-and-pop brick-and-mortars were at least other brick-and-mortars, the days when corporate stores could pass for cuddly faux-villains in Hollywood David-v.-Goliath tales like “You’ve Got Mail.” (Were you to cast the incorporeal Amazon as the villain to Meg Ryan’s Shop Around the Corner, the result would look more like John Carpenter’s still-frightening “The Fog.”) “You’ve Got Mail” was a big renter, and we mocked those who brought it to the counter. We preferred “Fight Club,” had all seen it perhaps too many times. We imagined ourselves as agents of chaos enacting our own tiny Project Mayhem, and fittingly our anti-Blockbuster antics did not stop at theft.

When a customer returned a porno in the box for “Pay It Forward” (presumably by mistake), we first played it over the store’s closed-circuit TVs and then reshelved it as normal: paid it forward, so to speak. When we noticed someone had defiled the cover of “Gladiator” by Sharpie-ing a generous cartoon phallus onto Russell Crowe, we didn’t remove the box; we took it as a cue and began enhancing the anatomies of other stars. I can’t un-see that “Dancer in the Dark” box featuring Björk with a droopy dick growing out of her forehead. I would occasionally bring a flask to work, pass it around, until the day the cap broke and my pants suddenly reeked of Captain Morgan’s.

We measured time by the movement of movies on the shelves. Surely, I thought, by the time “The Green Mile” goes from New Releases to Drama, I’ll have a better job and will be done with this place. I was astonished to learn that a coworker had been there since “Men in Black” was a New Release.

I solicited requests from my roommates for movies to add to our growing collection. When my store ran out of movies that I actually liked and wanted, I found myself pilfering copies of “Baby Geniuses” and “Patch Adams,” not really knowing why. Restless, I branched out. I printed up a bunch of rental cards with fake names, fake addresses and fake credit card numbers, then went to other Blockbusters and rented movies with free rental coupons. I kept the movies, knowing that when BBV Corporate would try to charge Roger O. Thornhill and Alan Smithee for their unreturned movies, it would be futile.

Things, you could say, were escalating.

At an all-night inventory, during which we scanned the barcodes of everything in the store, our naïve and extremely nice manager looked in shock at the discrepancy between what should have been in the store and what actually was: columns of numbers on dot-matrix print-outs that to me looked (as too many things did) abstract and meaningless, but to him was very real and spelled doom.

Christmas was coming. I bought a ticket to fly back home to Colorado. My dad lived there, though my mom lived in California. They weren’t legally separated, though I really had no idea what the status of their marriage was. There was a lot of nuance I didn’t want to parse. Whatever the situation was, I wanted it to have the unambiguous clarity of a Hollywood movie; I wanted it to think all my thoughts for me and ask nothing too challenging of me.

For the trip, I had my roommate give me a mohawk, shearing off the sides of my head. Planning on wowing the kids back home, I spiked up my ’hawk like a buzz-saw. Instead of mousse I used Elmer’s Glue because I’d heard that was the authentic thing to do, and I was young enough to think the word “authentic” means something different than it does, something less self-indicting than fetishizing other people’s experiences and doubting the validity of my own.

At work, I had problems getting my shifts covered, so I decided to quit. I had big plans for my final day, and in my head it was all going to be hilarious. My last shift coincided with another employee’s, and while he added to the movie-box graffiti, I glued a few random ones to the shelves. I imagined people trying to pick up a copy of “Toy Story” only to find it frozen in place, like the quarter-on-the-ground trick. This, to me, was the height of comedy and anti-corporate something. In reality, all that happened was a woman walked up to the counter with a box all sploogey with half-dried glue, asked if we had a bathroom where she could wash her hands. As I led her to the bathroom in the back, she said, “Looks like some kid played a joke on you.”

I flew back to Colorado. I sat around and didn’t bother to spike up my mohawk (washing Elmer’s Glue out of your hair hurts). Flaccid, the ’hawk looked less punk-rock, more Flock-of-Seagulls.

When I returned to L.A., buzz-saw shorn down to buzz-cut, I caught up with my former Blockbuster coworkers and found out that when news of the last inventory made it to corporate, they’d cleaned house. The manager had been fired. I tried not to feel guilty for my part in the evisceration of that store, but it was no good. If I’d hated Blockbuster because, like any large company, it valued its own ideology over individuals, I had let my anti-Blockbuster ideology eclipse any sense of individual consequences. If we’d taken “Fight Club” as our doctrine, we’d failed to register its surprisingly conservative element of playful anarchy systematized into its own form of fascism; we’d failed to register — much less navigate for ourselves — any nuance between extremes. We were teenagers.

I found another job: at a closet-size mall bookstore, a small subsidiary of Barnes & Noble. The corporate retail environment was the same there as at Blockbuster: same boarding-school rules of behavior, same vaguely religious fear of the all-seeing secret shopper. The infinite loop of peppy, pastel-sounding muzak had an early Nintendo quality to it. In the center of the store there was a large display of “Chicken Soup for the Soul” books, at which all aisles converged like lines at the vanishing point. One day, the assistant manager, mid-shift, shouted that he couldn’t stand the music anymore and stormed out, never to return. A few weeks later, I spotted him working at the scented candle kiosk in the mall’s adjacent wing. I fantasized about using Sue Grafton novels to spell out “I QUIT” on the shelf, but at that time she’d only gotten to “P Is for Peril.” The most anti-corporate rebellion I could muster was to refer to our parent company as “Barnes Ignoble,” thinking I’d coined the pun. But I didn’t steal anything; my career in thieving was over.

And yet when my roommates and I threw a party during which someone stole a good portion of the DVD collection I’d amassed, I was, without the smallest awareness of irony, devastated. Shortly after that, I was arrested for a DUI, and at the station the cop took an inventory of my wallet. He found half a dozen Blockbuster cards, each one with a different fake name. He asked me if I’d stolen them, and I said no. For some reason, I told him the truth. He just chuckled and said, “I think it’d be best if I throw these away. What d’you think?” I nodded, and he ninja-starred the stack into the trash.

The last time I was in a Blockbuster would have been in 2007. After living in Los Angeles for seven years, I was about to move east for grad school. My apartment was a block away from Cinefile Video on Santa Monica Boulevard, a store with a mission statement of snark that organized movies by whimsy, putting “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape” and “Rain Man” in the “Method Acting is Retarded” section — in short, the sort of place I would have loved to work at. For years, that’s where I’d been getting (and paying for) my movies, but this was my final week in L.A., and I was on a nostalgic jag. So I drove to the nearest Blockbuster for an old eye-shock of the aggressively lit yellow and blue. I noticed that they now carried the Criterion edition of “Down by Law,” but instead I selected “Love Actually,” one of those movies that thinks thoughts for you but for which I had developed a shameless affection.

Blockbuster was a strange place to go for a blast of nostalgia, since its overhyped, overstocked and overwhelming NEW shelves were altars to the present, each movie allowed a fruit-fly lifespan. But there was something perversely comforting about being there again: the sense that everything in life could be categorized as either comedy or drama, and of course there was the surly teenager behind the counter. I hoped he was judging me, had my whole psychological profile based on my movie selection; I hoped he was busy cultivating his own disaffection here, practicing his own craft of antagonism for the day it could find a better form of expression. Turned out, I didn’t have a membership anymore. I had to open a new account, with my real name.