Do you ever feel that Christmas, the most celebrated and supposedly sacred holiday on the American calendar, has long since lost its spiritual core and become little more than a soulless annual smörgåsbord for the consumer capitalist giant? If so, then you’re not alone. For years now, the Gallup polling firm has repeatedly concluded that a majority of Americans, sometimes as many as 85%, feel that Christmas has become too commercialized.

Nonetheless, Americans’ yearly griping over the Christmas season’s transformation from solemn observance of the birthday of Christ into an orgiastic sacrifice to the pagan retail gods hasn’t exactly expunged commercialism from the season. Year after year, Christmastime provides an excuse for thousands of parka-clad citizens to pitch a post-Thanksgiving Black Friday tent on retail pavement in their materialistic quest to get their greasy digits on the latest crappily made electronic hardware put together in questionable conditions overseas.

The fear of Christmas’ commercialization is also connected to concurrent fears that the holiday is being thoroughly secularized by angry hoards of lawsuit-wielding atheists, liberals and, apparently, Radio Shack. Catholics (but not all Catholics) and evangelicals alike fear that the commercialization of Christmas is a form of secularization that dilutes the holiday’s Christian meanings. Hence, religious conservatives have turned their notion of a “War on Christmas” into an annual ritual through which they can express their endlessly expanding persecution complex. The Fox News Network, a 24-hour media dispensary of white conservative outrage, has for years made the idea of a “War on Christmas” an integral part of their attempt to score high ratings from lily-white reactionaries petrified by the thought of American culture shifting its focus away from “Leave it to Beaver” land. Heck, one of Fox News’ former anchors, John Gibson, even wrote a book on the “liberal plot” to destroy Christmas (for a hearty laugh, read the book’s Amazon reviews).

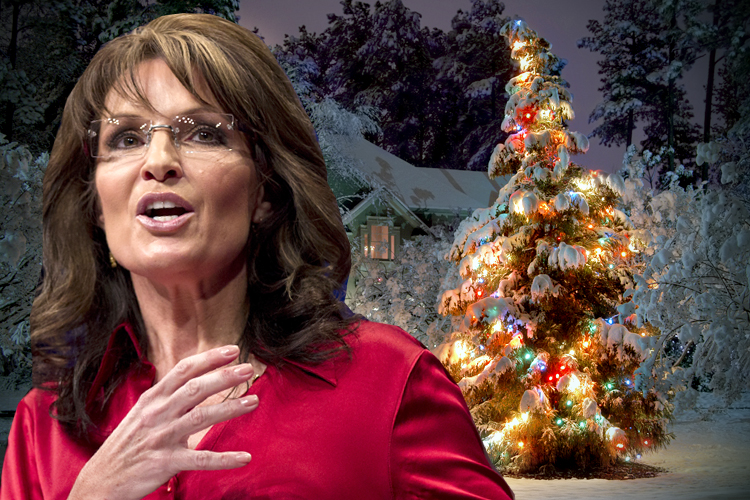

Never one to miss the chance to part conservatives from their cash, former Fox News commentator, half-term governor of Alaska, and perennial punch line Sarah Palin recently published her own “War on Christmas” screed, in which she defiantly reclaims Christmas’ Christian heritage from the angry claws of a host of boilerplate boogeymen, especially atheists and liberals, who, according to Palin, are interchangeable. Palin’s book is also available in a four-hour audio format read by the former governor herself, which should give U.S. agents at Guantanamo Bay a new tool to coax information out of would-be terrorists. Despite the heavy marketing campaign that accompanied Palin’s book, it debuted to reviews as chilly as the winter air and flopped on release, suggesting that perhaps there yet remains some last shred of karma in the universe. Whether Palin recognizes the irony of complaining about the commercialization of Christmas while also trying to capitalize on that commercialization via book sales remains to be seen, but don’t hold your breath.

So, has Christmas really been unmoored from its truly sacred origins and recast as a cash-register-feeding tribute to the gods of the marketplace? The short answer is “no.” In an American context, Christmas has always been a decidedly commercial holiday, and it was created as such by Americans who sought to reconcile paradoxical feelings that framed capitalism as a system that reduced human virtues to a series of vacuous commodity exchanges, but also facilitated the economic and social freedoms that eventually defined American culture.

As historian Stephen Nissenbaum writes in his book, “The Battle for Christmas: A Cultural History of America’s Most Cherished Holiday,” Christmas’ commercial trappings date all the way back to the 1500s via old European traditions that cast the winter season as a time of excessive celebration and symbolic inversion of traditional social orders.

In agricultural societies, December was the only time of the year when fresh meat was available after the slaughter, and the lack of refrigeration meant that meat had to be consumed quickly. Meat consumption, when combined with the end-of-the year availability of alcohol, turned the Christmas season into a season of excess. “Christmas was a season of ‘misrule,'” Nissenbaum writes, “a time when ordinary behavioral restraint could be violated with impunity.” Servants could act as masters and the rich would bow to the poor, and such “misrule” and inversion of social orders entailed all types of debauchery, from binge-drinking, to gluttony, to sexual deviancy. It’s no wonder that early American Puritans rejected Christmas as an anti-Christian, pagan-influenced, immoral booze-fest.

The association of Christmastime with “excess” survived into the 19th century, an era that forever fused the Christmas season with excessive luxury via capitalist consumerism in the collective American psyche. As Nissenbaum notes, 19th-century Americans lived in a transitional time, during which old seasonal rhythms were losing their influence over social behavior. “Urbanization and capitalism were liberating people from the constraints of an agricultural cycle and making larger quantities of goods available for more extended periods of time,” Nissenbaum observes. But the memory of old seasonal rhythms, with their emphasis on excess and celebration, died hard, and these old memories helped assuage the fears of a growing 19th-century American middle class that capitalism would supplant traditional virtues of frugality and citizenship with the hollow calls of luxury and excess.

In the midst of the great 19th-century Market Revolution, buying luxury goods became more possible, but remained suspect among Americans who had not yet fully equated consumer capitalism with civic duty. But, as Nissenbaum describes:

Christmas came to the rescue. For this was one time of the year when the lingering reluctance of middle-class Americans to purchase frivolous gifts for their children was overwhelmed by their equally lingering predisposition to abandon ordinary behavioral constraints. Christmas helped intensify and legitimize a commercial kind of consumerism.

In 19th century America, a new urban middle class developed along with a transformation within the American home. Domestic spheres became nurturing havens of refuge from the increasingly commercialized and heartless capitalist public marketplace. Yet, even as middle-class Americans criticized the growth of a consumer society, they couldn’t escape the fact that it was that very society that gave them steady incomes and the purchasable middle-class comforts that turned homes into shelters from the commercial world.

The growth of middle-class domesticity also involved a reshaping of the holiday season into a more child-centric celebration. Before the 19th century, children had been treated as smaller versions of adults. The mid-19th-century culture of domesticity, however, made kids “the center of joyous attention,” during which at least one aspect of Old World Christmas traditions, the temporary inversion of social hierarchies, was preserved. In an echo of Christmas celebrations that saw masters dote on servants, American parents, traditionally the authority figures, bestowed gifts upon their normally dependent children. As Nissenbaum notes, “a commercial Christmas thus emerged in tandem with the commercial economy itself, and the two were mutually reinforcing.” Indeed, it’s difficult to conceive of an American Christmas without consumerism.

Among the first retailers to cater to the need for gifts for children at Christmas were publishers and booksellers. By the 1830s, book producers had created a new holiday gift unto itself: the “gift book,” which was a modestly priced collection of poems, stories, essays and pictures that was published at the year’s end to coincide with the holiday shopping season. Gift books were immensely popular with kids who received them under the bedazzled domestic pine. Even Christmas trees, as historian Penne Restad reminds us in “Christmas in America: A History,” were used to encourage holiday consumption. American Protestantism at the time viewed “financial success as an indicator of faith,” and the various trinkets, toys, and other miscellaneous gifts that were “stored beneath an imposingly decorated Christmas tree created a powerful icon of the emerging American Christmas.” That icon was decidedly commercial: the Christmas tree served as a gathering place for the consumerist exchange of purchased items, and this tradition lives on today, giving the American economy a major boost every holiday season.

Christmas, then, forever legitimized the consumerist ideology in American society. Far from becoming too commercial, Christmas has always been inescapably commercial. Even the much-lamented early arrival of “Black Friday” and the Christmas shopping season dates back to the 19th century.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, no example better highlights Americans’ paradoxical rejection and embrace of holiday consumerism than the 1965 television special, “A Charlie Brown Christmas.” As J. Christopher Arrison writes over at Culture Ramp, “weary disillusionment with the commodification of the holiday season is a central theme” of the “Peanuts” special: “Charlie Brown bemoans little sister Sally’s requests to Santa (“How about tens and twenties?”); Lucy’s unrequited lust for real estate; and his dog Snoopy’s attempt to win money by costuming his doghouse with tacky lights.” For many Americans, the special’s central moment comes when blanket-toting Linus van Pelt delivers a heartfelt soliloquy on the real (Christian) meaning of Christmas — a truthful blade cutting through the commercial cloak that has been draped over the holiday.

American Christians, especially conservatives, have long celebrated Linus’ monologue, and “A Charlie Brown Christmas” in general, as a lone, exemplary mainstream affirmation of Christmas’ true religious meaning in an otherwise secularized and commercialized society. It’s all the more ironic, then, that “A Charlie Brown Christmas” is the ultimate example of the symbiotic relationship between Christmas and consumerism in America.

The TV special was sponsored by the Coca-Cola company, and, as Arrison notes, the original airing featured multiple Coke product placements. In the opening skating scene, Linus flies directly into a Coca-Cola sign, which was replaced with a “danger” sign in later broadcasts. In another scene, the Peanuts gang launches snowballs at a Coca-Cola can. Coke’s website even has an article, the “Secret history of Charlie Brown’s Christmas,” that details the company’s integral involvement in the creation of the timeless holiday special. Such a history wraps multiple layers of irony around Linus’ claim that Christmas had become “too commercial.”

So, does the inseparable history of Christmas and commercialism mean that Christmas has no spiritual meaning and that consumer capitalism is necessarily bad? Of course not. Despite its pagan roots, Christmas remains for many observant Christians a major celebration of their faith, and the giving of gifts during the season can be traced back to the Magi’s giving gifts to the infant Christ. Moreover, one need not be religious to appreciate the Christmas season’s festive celebration of family, goodwill toward fellow humans, and eye-pleasing decoration of pine trees and suburban Chicago houses. And there remains the obvious fact that rampant spending in a consumer-driven capitalist economy bodes well for America’s overall economic health.

While there are multiple, valid criticisms to be made of the hollowness of consumer capitalism, the fact remains that it’s the linchpin of the American socioeconomic order. Pretending that Christmas has been, or should be, separate from the American capitalist system is both foolhardy and at odds with American history. Of course, this doesn’t mean that you should go out after Thanksgiving and buy another TV that you don’t need to watch a million crappy channels that you don’t want. Christmas commercialism is a long-established American tradition, but don’t let buying things for your friends and family supplant actually enjoying the presence of your friends and family. Family togetherness, more than anything else, should also be an American tradition, even at Christmastime.