In 2000, the Coen brothers released their first version of The Odyssey: a rambling, comic adventure set in the Depression-era South that lifted its title and some imagery from Preston Sturges. That was, of course, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, one of their most financially successful films and the project that introduced newer generations of moviegoers to vintage folk and Americana music. (The album from the film, one of the best-selling soundtracks ever released, has moved almost 8 million copies to date.) The film was built around and defined by its music, with soundtrack curation starting early in the production process under the guidance of album producer T Bone Burnett. More importantly, though, it was a narrative about music, and specifically about an ad hoc folk band whose members stumble into fame and fortune, accidentally finding a version of the treasure that first set them on their path. Almost without trying, they get ahead of the game.

In 2000, the Coen brothers released their first version of The Odyssey: a rambling, comic adventure set in the Depression-era South that lifted its title and some imagery from Preston Sturges. That was, of course, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, one of their most financially successful films and the project that introduced newer generations of moviegoers to vintage folk and Americana music. (The album from the film, one of the best-selling soundtracks ever released, has moved almost 8 million copies to date.) The film was built around and defined by its music, with soundtrack curation starting early in the production process under the guidance of album producer T Bone Burnett. More importantly, though, it was a narrative about music, and specifically about an ad hoc folk band whose members stumble into fame and fortune, accidentally finding a version of the treasure that first set them on their path. Almost without trying, they get ahead of the game.

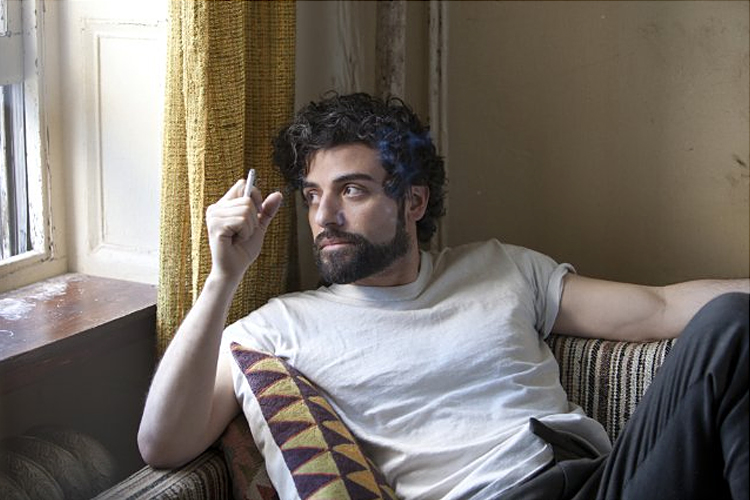

Inside Llewyn Davis — a great, troubled, moody, moving film — is a cracked mirror version of that story: darker, harder, more unable to resist life’s coldness and freak turns of fortune. It still riffs on Homer’s epic poem, and it even makes that theme explicit with visual references to Disney’s The Incredible Journey and a cat named, of all things, Ulysses. But the truest and most powerful inversion comes with the way the Coens sketch out the character and life of Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac) himself. Like so many Coen men, he’s out of step with everyone around him: always a little late, a little less knowledgeable, and a little more likely to be out of the loop. The film is free of conventional plot, opting instead for a more literary style that focuses on small steps, tangled relationships, and how our dreams almost never come true. Llewyn catches a break and gets to record on the potential novelty hit “Please Mr. Kennedy,” but he turns down the chance of royalties for a quick payout so he can pay for a woman who already hates him to get an abortion. He travels halfway across the country to try and impress the owner of a major music club, and after giving a soulful solo performance, the manager simply responds, “I don’t see a lot of money here.” He ruins his friendships, wrecks his romantic relationships, and torments his family as much as himself.

Most frustratingly, while the Soggy Bottom Boys managed to cut a hit without even trying, Llewyn is doing everything he can to perform his music and make a connection with the audience, only to have listeners and managers consistently reject him. The more Llewyn tries to be honest in his music — talking about pain and heartache, love and loss — the more he’s ignored. The crowds at the club like the simpler, sweeter stuff, and he can barely hide his disdain for the goofy pandering of “Please Mr. Kennedy.” He tries to funnel that sense of being an outsider into his art, but the rawness only backfires. He plugs away but never gets anywhere.

What makes his disconnect work so well for the viewer is the type of music he’s playing. Folk and Americana (two huge, overlapping genres whose names I will probably use interchangeably here) are elemental types of music, rooted in tight harmonies, traditional lyrics, and oral histories passed down through song. They’re about death and trial, and about being on the outside looking in. They’re a tool for processing pain, and Llewyn Davis is very much a man in pain: depressed, unhappy, unsure of what to do, and unable to commit to any of the dozen directions his life is going. His music isn’t the blues, and it’s sure not rock or pop. It’s more curious, less certain. So while O Brother enjoys a certain juxtaposition and distance between the grimness of its music and its ultimately comic tone, there’s no such safety in Inside Llewyn Davis. Here, the dirges are foreboding, and you realize again how rooted this music is in dirty history and forgotten places, in immigrants and wars, in the methods that let us reconnect with the eternal feelings we always seek out in music, and that enable us to listen to songs over and over again to capture those fleeting moments where everything seems to come together. Even the pain.

That sense of using music to explore and express pain, and to try and get a handle on heartache, also made itself known in this year’s The Broken Circle Breakdown, a shattering musical drama from Belgium (and that country’s entry for the Best Foreign-Language Film category in this season’s Oscars). Cycling back and forth between different timelines, the film tells the story of Didier (Johan Heldenbergh) and Elise (Veerle Baetens), who fall in love, have a child, and then face the kind of torment every parent dreads when that child is diagnosed with cancer. In many ways, though, it feels like a counterpart to Inside Llewyn Davis: Didier is a bluegrass musician in a local band when he meets Elise, and he gushes to her about influential American artists like Bill Monroe, who helped create the genre. His passion for the music is infectious, and soon enough she’s performing with the band, and their numbers together act as signposts through their traumatic journey.

Like the Coens, writer-director Felix Van Groeningen lets entire songs play out in performance. These moments aren’t indulgences in either film, but rather crucial ways to reveal character and plot, and to highlight how these outsiders embrace American art forms as ways to connect with each other and their audiences. When Llewyn watches a soft-around-the-edges singer perform a lilting ballad, we don’t just get the song, but Llewyn’s inability to understand why that music clicks with listeners and his doesn’t, as well as a smartly executed song that, by being everything Llewyn isn’t, helps him stand out more for us. Or there’s the moment when Llewyn gives everything he has in a solo performance for a club manager, his voice soaring and tearing through us. We can feel his yearning. Similarly, at one point in The Broken Circle Breakdown, Didier and Elise are struggling to stay together, and we see that battle play out in an expertly staged performance of Townes Van Zandt’s “If I Needed You.” Look at the way Didier reaches his hand out to Elise, not knowing if she’ll offer hers, but unable not to try:

Van Groeningen also crafts a haunting, almost destructively sad rendition of “Wayfaring Stranger” that does more to convey the characters’ despair than anything else could (this clip includes some spoilers):

The Broken Circle Breakdown is not, you might have gathered, a cheery film. But it is a great one, brimming with love and loss. Its title is reverse-engineered from “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” a hymn from the early 20th century that was reworked into a folk song by A.P. Carter and popularized by the Carter Family. It’s a song that searches for hope and reunion in the next life, but there can only be reunion if there’s first a disintegration, and this film charts one way that might happen. It’s about the breaking of a circle whose remaking is hoped for but never seen, at least not here and now. The film’s about someone using music from another country and another time to achieve something universal and timeless, and about the struggle to live on the outside of life. The characters in this film understand implicitly the things that drove Llewyn Davis: that this stripped-down, elemental music and killer musicianship are powerful in ways we can’t name, able to transport us, to express the things we wish we’d said. In both films, we see people hanging it all out there trying to save their lives, hoping that a song can do what they never could. It almost never does, which is kind of the point. The music holds out hope of clutching hands on the golden shore, but when it stops, we’re still here, bound to ramble. It’s the yearning, the mourning, the trying that defines us and them, that keeps them coming back to this music of melancholy and hope. Of fighting against a tide.