In 1972, with the Vietnam War still raging, Democrats certainly hoped to make the large loss of American life a pivotal issue in their effort to oust Nixon. Washington Post cartoonist Herblock led the way. A long-term Nixon-hater, he graphically emphasized that Nixon’s war had cost twenty thousand lives. George McGovern, the Democratic nominee, ardently sought to exploit this large death toll. The only out-and-out antiwar presidential candidate of the entire Vietnam era, McGovern implored the electorate to “choose life, not death” when they voted in November. “Someone,” he insisted, “must answer for [the] 20,000 more dead, for 110,000 more wounded, for 550 captured or missing, for $60 billion more wasted in the last four years.”

Ultimately the most striking characteristic of McGovern’s candidacy was its spectacular lack of success. In 1972 the Vietnam War—and the high death toll of the Nixon years—simply failed to resonate with the electorate. Part of the reason was unconnected to casualties. The two main candidates simply ran very different campaigns. McGovern’s was a liberal insurgency that initially benefitted from the opening up of the nominating process to state primaries in which activists made a decisive difference. McGovern had trouble, however, transforming his primary momentum into the fall. At the Democratic Convention, in particular, he was slack and disorganized. His acceptance speech was made to a tiny audience in the early hours of the morning. He also picked a vice-presidential running mate who soon had to withdraw after he admitted undergoing electroshock therapy.

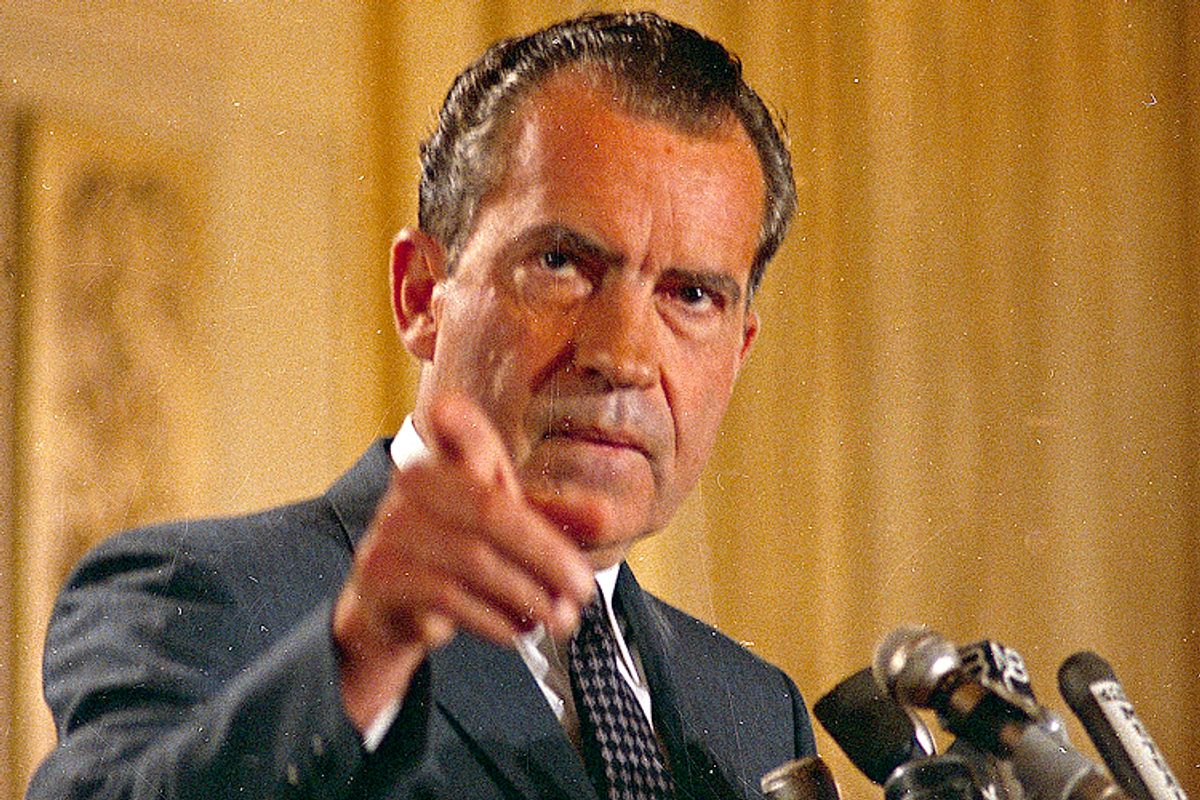

Nixon, meanwhile, sought to soar above the fray. He had already established his credentials as a successful international statesman, visiting both China and Moscow within the space of four months in the first half of the year. In the summer and fall he then implemented a detached Oval Office–centered campaign, while his aides played dirty. On presidential orders Nixon’s underlings worked hard to tarnish McGovern as a radical in cahoots with the most extreme antiwar protestors—those long-haired, and sometimes violent, demonstrators who “the great silent majority” had so little time for.

While this unseemly Watergate-tarnished campaign grabbed the nation’s attention, the actual fighting in Vietnam slipped into the background. This was surprising, for throughout 1971 the war had remained a major topic. In February and March, Nixon had seemed particularly vulnerable after media reports depicted South Vietnam’s incursion into Laos as a spectacular fiasco. Correspondents had been particularly eager to criticize the government’s clumsy efforts to minimize helicopter losses and use “misleading evidence” to claim the South Vietnamese had performed well. Then in the spring, with opinion polls revealing that 61 percent considered the war a mistake, the antiwar movement launched another bout of mass protests. The actions of veterans who opposed the fighting were particularly striking, as they discarded their medals and appeared on the media and before Congress. When John Kerry, the future senator, presidential candidate, and secretary of state under Obama, was called before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he dubbed the war “the biggest nothing in history,” adding, in a subtle rephrasing of the Korean War sound bite, “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?”

A year later, Nixon was able to prevent Vietnam from igniting as a major campaign issue. He began his reelection campaign by readopting the mantle of peacemaker. On January 25, just weeks before making the historic trip to China, he went on television to reveal that Kissinger had met a North Vietnamese negotiator on twelve occasions. In these secret sessions, Nixon explained, Kissinger had unveiled numerous initiatives to break the deadlock, but each one had been rebuffed by North Vietnam.

If this speech helped to defuse the charge that Nixon had made no moves to end the war, then his next televised address, on April 26, emphasized the success of Vietnamization. On the day he had assumed office, Nixon reminded his national audience that the American troop ceiling in Vietnam was 549,000. Our casualties were running as high as three hundred a week. Thirty thousand young Americans were being drafted every month. Today, thirty-nine months later, through our program of Vietnamization—helping the South Vietnamese develop the capability of defending themselves—the number of Americans in Vietnam by Monday, May 1, will have been reduced to sixty-nine thousand. Our casualties—even during the present, all-out enemy offensive—have been reduced by 95 percent. And draft calls bring them to zero next year.

As Nixon pointed out, even a major new North Vietnamese offensive failed to halt the inexorable decline in American losses. Vietnamization was one obvious reason. The other was that Nixon unleashed a true techno-war campaign, especially in the air, to bolster South Vietnam and counter the communists.

Hanoi had launched its Easter Offensive on March 30. It was a sustained three-pronged attack that placed intense pressure on South Vietnam during the spring and into the summer, but Nixon hit back hard. As he told his advisers, he was determined to “bomb those bastards like they’ve never been bombed before”— and he certainly had sufficient power at his disposal. Alongside the massive B-52s, which each had a payload of about twenty-two tons, the U.S. Air Force was now equipped with high-precision weapons that had been waiting for action since the 1968 bombing pause. As the historian Stephen P. Randolph points out, American aircraft could now “strike accurately from a higher altitude, avoiding the antiaircraft fire that had always been the greatest threat to strike aircraft. More significantly, perhaps, a single aircraft could attack with greater assurance of destroying a target than had been possible” during the 1960s. Nor was this all. On May 8 Nixon announced the mining of Haiphong Harbor. Within the space of just two minutes U.S. planes laid thirty-six mines. Without suffering any losses, they closed the major port through which North Vietnam brought in crucial supplies.

From Nixon’s perspective, this techno-war response was a clear success. By June it had helped halt the Easter Offensive, at a cost to Hanoi of about half the 200,000 troops it had thrown into battle. By October it had even contributed to a breakthrough in the negotiations. For the first time Hanoi agreed to a settlement that would leave Thieu in place. During November and December Thieu himself was the main obstacle to a deal: he balked, in particular, at an agreement that would permit communist troops to remain in the South. But after Nixon launched the massive Christmas bombing raids in December, Thieu was somewhat reassured both by minor additional North Vietnamese concessions and by the prospect that the United States would again bomb if North Vietnam violated the deal. On January 23 the Paris Peace Accords were finally signed. Four days later a ceasefire went into effect, bringing an end to the United States’ protracted involvement in the Vietnam War.

At home, meanwhile, Nixon’s way of war was, if not popular, then at least sufficiently blood-free to head off the type of domestic eruption that had brought down Lyndon B. Johnson four years before. Indeed, although a series of big battles unfolded throughout Vietnam, it was the South Vietnamese army that was doing the fighting and dying on the ground. American casualties, by contrast, dwindled to a point where on September 21 the MACV could happily announce that the past week had seen no combat deaths—the first time this had happened in seven years.

Nixon had long ago calculated that most Americans were prepared to endure such a war. He now appeared vindicated by opinion polls, which showed support for his Vietnam policy veering sharply upwards, from a low of around 45 percent just before the Easter Offensive, into the 50, 60, and even 70 percent range as a peace deal loomed. Then in November, in the only poll that really mattered, Nixon won reelection with a massive landslide victory. As a rueful McGovern conceded, Vietnam simply did not work for him as an issue. Why, he was asked? “When the corpses changed color,” McGovern acidly responded, “American interest diminished.”

For once Nixon wholeheartedly agreed with his political rival, but he had not been prepared to let this interest diminish of its own accord. When it came to discussing U.S. casualties in public, Nixon’s team was acutely aware of what to avoid, down to the smallest details. White House advisers, for instance, shied away from using casualty charts when briefing the press, fearing they would be too impersonal and set “the wrong tone.”

The Pentagon, meanwhile, was much more media savvy than at the outset of the war. Back in 1965 it had unwittingly helped to dramatize the bloody start of the fighting by helping ABC and CBS produce special TV broadcasts that vividly showed returning coffins and military funerals after the Ia Drang battle. By the 1970s it was much warier. When one network asked for official help to produce a ninety-minute color documentary that explored the reactions of families to the death of their next of kin in Vietnam, the Pentagon’s response was curt. It considered “such coverage in extremely poor taste,” explained the army’s PI chief, who added that no one in the military should give “any encouragement to such a morbid project.”

As well as realizing what to avoid, Nixon also knew what to stress. By 1972 his central calculation was that the public cared only about current losses. This might seem patently obvious, but other key players often reached a very different conclusion. The military, for one, tended to think about the future. In devising military campaigns, commanders kept one eye on ultimate cost of the war. In their firm view the overall death toll would be much lower if they maintained relentless pressure on the enemy. Nixon increasingly dissented, however. He recognized that Hamburger Hill had starkly exposed the domestic danger of this logic. Although he subsequently sold the Cambodian incursion as a way of saving future lives, he had long since instructed his commanders to fight the war with one eye firmly fixed on each week’s casualty total.

The Democrats, meanwhile, increasingly focused on past losses. Throughout 1972, in particular, they talked constantly about all the casualties suffered since Nixon had taken office, in an effort to emphasize his broken pledge to end the fighting. Nixon, of course, was not averse to delving back in time, but his reference point was quite different. He emphasized the bloodiness of Johnson’s war as a way of drawing attention to the happier state of current affairs. As one of his 1972 campaign posters starkly declared, under Nixon American casualties had declined 95 percent.

When the peace accords were signed in January, Nixon could also boast another casualty success: the return of the American prisoners of war from communist captivity.

From the start of his presidency Nixon had recognized the power of this issue. In May 1969, abandoning Johnson’s “quiet” diplomacy, Laird had launched a “go public” campaign. Ostensibly its aim was to “influence world opinion to the point that Hanoi will feel compelled to afford proper treatment to U.S. POWs.” But Laird also had one eye fixed firmly on the home front. He hoped to “marshal public opinion,” according to one account. So did Nixon. By the end of 1969 the two men were no longer content to rely just on Vietnamization to defuse the antiwar movement. They also wanted a positive rallying cry to energize their base. The American POWs seemed ideal. By emphasizing that the United States would fight until every prisoner was returned, Nixon hoped to remobilize the home front—or at least his “great silent majority.” With public support solidified, he believed that Hanoi would come to terms at the peace table. Because these terms would include the prisoners’ return, he could then show Americans a clear success.

Although Nixon’s publicity campaign was intensive, he never completely controlled the debate. North Vietnam itself tried to manipulate POWs. Long before Nixon’s election Hanoi had threatened to try downed airmen for war crimes—a clear way of pressuring the United States to halt its bombing campaign. It then continued intermittently to release small groups of prisoners into the hands of prominent American antiwar activists—with the obvious intent of trying to compound the war’s divisiveness inside the United States. Increasingly, moreover, Nixon also found that the POW issue was a double-edged weapon at home. Although the League of Families—the most powerful of the prisoner groups— was behind him for much of the time, other relatives argued that the prisoners would return home quicker if he simply ended the war. Increasingly, even the league itself was impatient, and in 1971 it began pressing him for a firm date for an American withdrawal.

Whatever the daily frustrations, Nixon’s “go public” campaign clearly helped to make the POWs a dominant issue in American politics. By the early 1970s tens of thousands of bumper stickers appeared on cars. Hundreds of supportive resolutions were introduced in Congress. And no presidential speech on Vietnam was complete without a pledge not to “abandon our POWs and our MIAs, wherever they are.” In 1973, when the peace accords finally brought these prisoners home, Nixon was naturally quick to declare victory. But he also claimed much more: vindication. In May, after hosting a special White House dinner for the returned POWs, he recorded feeling a sense of “joy and satisfaction . . . that they, who were so completely courageous and admirable, seemed to consider the decisions I had made about the war to have been courageous and admirable ones.”

Nixon’s achievements—if not his sense of vindication—were to prove extremely fleeting. Within months, in fact, they would turn out to be pyrrhic victories, which not only constrained American power and credibility but also helped to destroy his presidency.

Vietnamization was a case in point. Inside the United States the slow withdrawal might have numbed the political debate. But for many of those Americans who still had to fight Nixon’s war the pointlessness of the exercise engendered a profound sense of disillusionment. This was an “army in anguish,” according to a series of Washington Post special reports published in the fall of 1971. No one wanted to be the last American killed, the Post revealed, a conviction so strong that some troops now reported “false positions to avoid combat.” In one widely reported incident, fifty-three men even refused to launch a dangerous nighttime mission—a refusal that became a cause célèbre when the general in charge refused to discipline them. Even such insubordination paled next to stories of “fragging.” It was a term the military hated and tried to dissuade reporters from using, on the grounds that it “trivialized a serious offence.” By 1971, however, officials had to concede that the intentional targeting of friendly soldiers had occurred, although they challenged the claim that it had “become fairly commonplace.”

Drug abuse presented a similar problem. During 1970 and 1971 media reports of a drug epidemic were rife, as soldiers apparently turned to narcotics to blot out the whole Vietnam experience. The Pentagon was quick to demolish the more exaggerated of these reports—such as stories of stoned soldiers shooting down an American helicopter gunship. But faced with TV reports showing GIs at a “pot party,” military spokesmen were again forced to admit there was a problem, this time with the qualification that the rest of American society faced a similar problem.

In June 1973 the Pentagon’s final accounting provided statistical evidence to demonstrate the extent of the army’s anguish. As well as the overall figure of 45,958 Americans KIA during the war, officials announced that a further 10,303 U.S. servicemen had died of non-combat causes. Although almost half of these were from aircraft or motor vehicle crashes, a significant proportion stemmed from the specific problems of the Nixon years. Thus there had been 1,172 suicides, 1,163 homicides, and 102 deaths from drug abuse. Fragging fatalities had actually declined toward the end, from a high of thirty-seven in 1969 to twelve in 1971 and three in 1972. But the overall trajectory of fragging incidents was still worrying, leaping from 126 to 333 between 1969 and 1971.

While this sense of decay ate away at the military in Vietnam, Nixon’s techno-war escalation increasingly riled political elites at home. Determined to prop up South Vietnam in an election year, Nixon’s casualty sensitivity had not extended beyond American lives to enemy noncombatants. “Now, we won’t deliberately aim for civilians,” he told his senior advisers at one point in 1972, “but if a few bombs slop over, that’s just too bad.” In Nixon cold calculation the American electorate was principally concerned with U.S. losses; it cared far less about what happened to civilians.

In a narrow sense Nixon was correct, for he won reelection by a landslide in November. But the consequences of his deeply cynical war-making strategy were profound, especially for the more than 1,500 civilians who died in the Christmas bombing raids. Nor in the Vietnam era was the domestic mood entirely inured to such deaths. While protestors had long placed the impact of bombing at the heart of their indictment against the war, the death of 109 civilians in the village of My Lai had been a black stain for most of Nixon’s presidency, with the antiwar movement predictably seizing on it to claim that the United States was no worse than its reviled enemies of the past.

Nixon’s Christmas bombing naturally rallied these protestors in another bout of rage against the war, where they were joined by a growing number of mainstream voices who dubbed these raids a “shameful” and “monstrous deed.” “The rain of death continues,” declared the Boston Globe in a typical comment. “Are we now the enemy—the new barbarians?” asked the New York Times. On Capitol Hill the mood was particularly heated. Even Hugh D. Scott (R-PA) the Senate Republican minority leader, stated publicly that he was “heartsick and dispirited.” On the other side of the aisle Mike Mansfield, the Democratic majority leader, said that patience had finally collapsed. As soon as the new Congress convened in January he pledged to press for legislation to end the war immediately. Nixon was often dismissive of opposition from these quarters. The media and Congress, in his eyes, were liberal bastions to be outwitted, smeared, and beaten. But with an increasingly assertive Democratic Party in charge on Capitol Hill, Nixon recognized that he had to conclude a peace deal before the end of January. He also knew that Congress was unlikely to support future efforts to bolster South Vietnam with American force. The poison his Christmas bombing had injected into the congressional debate had seen to that.

Soon after, Nixon’s authority over Congress collapsed entirely, as Watergate shifted from a minor campaign issue to a major political scandal. In Nixon’s jaundiced view, Watergate was the central reason why Vietnam was finally lost in April 1975. The Democrats in Congress, he charged, were so emboldened by the scandal that they denied both him and his successor “the means to enforce the Paris agreement at a time when the North Vietnamese were openly violating it.”

Yet Nixon’s postwar scapegoating ignored two crucial facts. One was that his own bombing, especially during December 1972, had already destroyed congressional support for bolstering South Vietnam. Even without Watergate Nixon would have found it difficult to revive his techno-war campaign in response to a new North Vietnamese attack. The other was that the relationship between Vietnam and Watergate was one of cause as well as consequence. While the specific break-in stemmed from the Nixon White House’s desire for dirt on the Democrats, the overall scandal was inextricably entwined with his way of waging war in Vietnam. Indeed, the administration’s first steps along the path of illegality had come in the spring of 1969, when it used wiretaps to trace who had leaked the story of the secret Cambodian bombing. Later the president’s men had lengthened their stride with efforts to smear antiwar radicals, including burgling the office of a leading antiwar figure’s psychiatrist in an unsuccessful effort to get damaging material to use against him.

These were just two of the “White House horrors” that Nixon was desperate to cover up after June 1972, when the Watergate burglars were caught. When this effort crumbled, Nixon left behind a debilitated presidency. In 1973 alone, Congress cut off funding for the continued bombing of Cambodia and passed the War Powers Act that limited the president’s power to deploy troops overseas. Then in 1975, with a new North Vietnamese offensive poised to overrun South Vietnam, legislators refused to vote for aid, let alone any new use of air power. Amid political recriminations in Washington and television images of a chaotic evacuation in Saigon, the United States finally lost its war in Vietnam.

The Vietnam Syndrome

This dismal end was an important contrast to earlier wars. Casualty debates had often spilled over into the postwar era, most notably after 1918 when many Americans had recoiled from the prospect of ever sending their boys off to another European slaughter. Yet at least World War I had had the saving grace of ending in victory. Vietnam had no such upside. After 1975 one of the few things ex-doves and ex-hawks could agree on was that the lives lost in Vietnam were “utterly wasted”—doves because they still thought the war immoral and unnecessary, hawks because they believed that battlefield deaths ought to have been sustained in a winning cause.

In the years after Vietnam this sense of utter waste permeated the political debate. As well as the war’s miserable outcome, memories lingered of bloody battles waged for no purpose, with Hamburger Hill as the prize exhibit. In this sense the 1970s were an eerie reprise of the 1920s. Although few embraced the term “isolationist,” many did agree that American boys should “never again” be sent into a similar war. It was a belief that, as in the 1920s, was reinforced by an influential strand of popular culture, as veterans, novelists, and filmmakers all emphasized the wounds the war had created and then left to fester. But this time the “never again” mentality was also stiffened by statistically based academic research.

In 1972, while the war still raged, the political scientist John Mueller published a book that contained a simple and powerful idea. Popular support for the Korean and Vietnam wars, Mueller argued, had declined as casualty figures mounted. Chiming neatly with the prevailing mood, Mueller’s thesis quickly became accepted conventional wisdom. Thereafter many prominent voices not only believed that “support for Vietnam [had] buckled as the body-bag toll mounted,” but also projected this idea forward into future wars, claiming that the casualty-sensitive public would no longer accept conflicts with a large number of American losses.

Cold War hawks were horrified. Convinced that the United States still had to wield every weapon in its arsenal to contain—and even rollback—communism, these hawks tried to confront this new mood head on. Ronald Reagan was their cheerleader. “For too long,” Reagan declared during his successful presidential campaign in 1980,

we have lived with the “Vietnam syndrome”. . . . We dishonor the memory of fifty thousand young Americans who died in that cause when we give way to feelings of guilt as if we were doing something shameful, and we have been shabby in our treatment of those who returned. They fought as well and as bravely as any Americans have ever fought in any war. They deserve our gratitude, our respect, and our continuing concern.

As this speech suggested, a key component of Reagan’s agenda for ending the Vietnam syndrome was to honor the war’s casualties, both living and dead. The former were a particularly big group, largely because better medical facilities insured that the wounded-to-killed ratio had been massively improved. After the war, however, this tremendous achievement meant that a higher proportion of veterans still carried some form of physical disability. They were not the only lingering sufferers. Some veterans also came down with serious illnesses, including cancer, which they traced to their exposure to chemicals used against the enemy, especially Agent Orange. Many more were physically fine but mentally scarred. Unlike in World War II, where most psychiatric cases had occurred under extreme battlefield conditions, in Vietnam the problem was the exact opposite: relatively few instances in the fighting theater, but a delayed reaction when veterans returned home.

During the 1980s the United States tried to come to terms with these casualties. While Reagan publicly challenged the “unjust stereotype” of the traumatized outsider, veterans groups were now better organized and Congress more open to meeting their demands than after previous wars. The result was a series of practical gains. Agent Orange victims received compensation in a court settlement, health care providers recognized post-traumatic stress disorder, and the government made some effort to improve veterans’ facilities. In 1982 the Vietnam dead even received their own national monument. Conceived in controversy, the memorial’s moving simplicity soon proved a hit with families, veterans, and tourists alike—so much so that it rapidly became Washington’s most visited monument.

Yet talking about or memorializing Vietnam was one thing. Overcoming the nation’s acute sensitivity to fresh combat casualties was quite another. Even Reagan, for all his much-vaunted gifts as the “great communicator,” was unable to shift the debate away from the likely human cost of Cold War interventionism.

Reagan, in fact, could not even drum up domestic support for the use of force in Central America. This was significant. El Salvador or Nicaragua were not distant flashpoints like Korea or Vietnam. They were in America’s “own backyard.” Even in the casualty-shy 1920s, when memories of World War I had hung heavily over U.S. foreign policy, the United States had sent marines to Nicaragua. In the early 1980s, though, when Reagan wanted to roll back communism in the region, public opinion remained a major obstacle. In March 1981 one poll found that only 2 percent favored sending U.S. troops to El Salvador. A year later a string of other polls reported that between 60 and 74 percent thought that El Salvador was likely to become another Vietnam. As Reagan later conceded, “after Vietnam, I knew that Americans would be just as reluctant to send their sons to fight in Central America, and I had no intention of asking them to do that.”

Although the military largely agreed, during the 1980s it had to work on the assumption that at some future point a president would again place America’s boys in harm’s way. Given the public’s casualty shyness, Pentagon planners searched for ways to make such a war domestically palatable. They began by revamping media relations. In Vietnam the lack of censorship had enabled reporters like Neil Sheehan and Jay Sharbutt to emphasize the bloodiness of battles like Ia Drang and Hamburger Hill. The military was desperate to avoid a repeat, so desperate, in fact, that when Reagan invaded Grenada in 1983 the Pentagon implemented a complete news blackout. There was no press pool, no accreditation, and not a single reporter with American forces during the operation.

The media immediately remonstrated. With powerful owners, editors, and reporters all emphasizing the public’s right to know, the military was forced to rethink. Within weeks the Pentagon’s press office pledged to allow the media “complete access” to future operations “so long as it [did] not violate the security of our operation or endanger the lives of our forces.” To work out the details the Pentagon created a panel of fourteen PI officers, former journalists, and academics. Headed by a former MACV PI chief, it soon unveiled a range of improvements, including granting correspondents access to the war zone in press pools and a voluntary set of guidelines that all news organization ought to subscribe to.

This attempt to forge a new military-media relationship was by no means successful. By the 1980s there were simply too many lingering resentments on both sides of the divide, which were apt to erupt in controversy even without a major war. The military complained first. In the spring of 1985, when the Pentagon trialed its new censorship system, flying ten reporters to Honduras to watch a secret training exercise, officials were appalled when one section of the media produced unauthorized and “speculative stories.” But the media soon hit back. A year later, when Reagan launched a strike against Libya, correspondents on board one carrier were in uproar when the navy first kept them in the dark about the missile launches and then outright lied to them.

Faced with these failures, the military could at least take some comfort from internal studies suggesting that media reporting was not the main danger to future operations. Casualty totals still held this dubious distinction. “What alienated the American public in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars,” an army study concluded in 1989, “was not news coverage but casualties. Public support for each war dropped inexorably by 15 percentage points whenever total U.S. casualties increased by a factor of ten.” If this were true, tinkering with media relations would not fix the problem. What was needed was a whole new approach to modern warfare. Under Nixon, the military’s mission statement in Vietnam had included a clear injunction to keep losses to a minimum. Under Caspar Weinberger, Reagan’s defense secretary, an even deeper change was introduced. In a major speech in November 1984 Weinberger revealed six “tests” to be applied when “weighing the use of U.S. combat forces abroad.” The so-called Weinberger doctrine included using force only as a last resort, devising objectives that were clear and attainable, ensuring that troops had sufficient resources to win, and obtaining the full support of Congress and the public.

As the Cold War came to an end, then, the searing Vietnam experience continued to linger. For Johnson and Nixon, it was a war that had thrown up different problems, and not just because Johnson had steadily expanded the U.S. commitment while Nixon had sought to gradually withdraw. Johnson’s war had also been plagued by paradoxes—the playing down of American involvement while drawing attention to the tragedy of mounting casualties; the presiding over a military that provided unprecedented amounts of casualty information but was still dogged by major questions about its credibility. Nixon, too, had faced his own paradoxes, not least in escalating a conflict at the same time he was seeking to disengage. But the central theme of Nixon’s war was the pyrrhic nature of his victories. From Nixon’s narrow perspective, his strategy worked perfectly in 1972. His attempt to reduce American casualties without precipitating South Vietnam’s collapse helped him achieve the central goal of his first term: reelection. Within months of his resounding landslide, though, Nixon’s presidency—and its legacy—was in ruins. The complicated consequences of trying to bomb in secret were part of the cause, but so were other strands of his strategy. Nixon’s Christmas bombings might have helped force a deal, but they further eroded congressional support not just for Vietnam but for all forms of presidential war-making. His Vietnamization strategy might have muted the public’s opposition to the war, but it generated major problems for the U.S. military and, above all, proved ineffective against the renewed communist onslaught in 1975.

In the wake of defeat, the U.S. government tried to learn the appropriate lessons. As well as reconsidering military-media relations, officials thought long and hard about the conditions under which the public would support the use of force—and the prospect of casualties—in the future. Sometimes, they looked back beyond Vietnam to an earlier era when the media had appeared more manageable and the public less skeptical. Of course, even during the two world wars and Korea, the government had always faced searching questions about the veracity of its casualty information. But Vietnam had clearly changed the rules of the game. Trust in government was much lower. The media was even keener to probe for the story behind the official narrative. And the whole debate was now even more sensitive to the human cost of war. These were all legacies that the two Bushes would have to grapple with in the post–Cold War era, as they took the United States into war against a new set of enemies.

Excerpted from “When Soldiers Fall: How Americans Have Confronted Combat Losses from World War I to Afghanistan” by Steven Casey. Copyright © 2014 by Steven Casey. Reprinted by arrangement with Oxford University Press, a division of Oxford University. All rights reserved.

Shares