The ten-year anniversary of Brian’s injury is coming up. A lot of people in the veterans’ community call it their Alive Day. Brian calls it his Phoenix Day—I strongly prefer that term. The imagery of the phoenix arising from its own ashes is powerful. It isn’t just about staying alive, it’s about renewal. The journey Brian and I have been on hasn’t been trying to survive and get back to the way things were before, it has been about forging a new normal—one that is in many ways better than the old.

There’s been so much talk about post-traumatic stress, including arguments about whether or not to drop the “disorder” and simply call it PTS , or change the D to an I for “injury” to emphasize that it has a precipitating event rather than being caused by some inherent weakness, as part of efforts to destigmatize help-seeking, particularly among combat veterans. The flip side, post-traumatic growth, has been largely ignored. But that aspect to the aftermath of trauma is just as real. I came home keenly aware of how lucky I am to live in America today, where I have access to health care, electricity, the comforts of modern life—and where the chances of my loved ones dying due to a terrorist attack pale in comparison to the likelihood they will die from diseases caused by overconsumption.

And over time, Brian and I both came to deeply feel our connection to our fellow citizens and be highly conscious of the responsibilities that laid upon us to contribute to society. We are both convinced that having suffered, going through the crucible of war, drove development of our morality. Hermann Hesse said, “Who would be born must first destroy a world,” echoing Carl Jung’s “There is no coming to consciousness without pain.” And so, like a chick hatching from its shell or the phoenix rising from its ashes, rebirth and renewal sometimes only come from wrenching displacements of the world you knew.

Getting to where we are today has not been easy. I liken it to the stock market—a jagged line with lots of ups and downs, but over the stretch of years the upward trend is clear. People have often asked me why I stayed, and I still can’t answer that question satisfactorily. My motivations are tangled. I loved my husband, but didn’t always like him. I felt an obligation to care for him, one that was mixed up in the military ethos of “Leave no fallen comrade behind.” But sometimes the desire to run from that responsibility was so strong that I had to find ways to tie myself to him for fear that I wouldn’t stay—getting married, having a public wedding, buying a house: all of these things served as ways I could bind myself, make it harder to leave in a fit of pique. I’m not a religious woman, but in the early years I sustained myself on faith: a steadfast conviction that he would get better, if I tried hard enough, waited long enough, hoped hard enough, he would get better. And he did.

It’s made me feel terribly awkward when giving dating advice. When boyfriends treat my friends like garbage, I say, “Leave him!” And they say, “But you stayed. And now look at Brian!” It seems I’ve lived out the fantasy I shared with so many dumbass girls in high school: if you just love that bad boy hard enough, he’ll change! I have to explain, “But Brian had a TBI and PTSD—there were reasons for his problems, and a path to recovery. There’s no therapy for asshole.”

Early on in our marriage, Brian would accuse me of trying to change him. “This isn’t about me changing you,” I responded. “This is about the changes that naturally occur when you grow up. Cleaning the house, paying bills, being responsible—that isn’t me trying to turn you into someone you’re not. That is me expecting you to go through the transition that everyone goes through when they become adults.” It baffled me. Shouldn’t all this have already happened during his first marriage, or when Sonja was born?

One day he confessed, “Sometimes I feel like . . . all the development that was supposed to happen, when I got the brain injury, it just halted. I stopped progressing.” But he hadn’t stopped—just paused.

During some of the rougher times, two memories helped sustain me. One was a friend of mine from high school, who built a lasting relationship with his girlfriend after they had a daughter together, telling me, “I don’t always love her, but I always like her. There are weeks or even months when I’m not that physically attracted to her—I’ve even felt attracted to other women. But I’ve always been profoundly interested in her, how she thinks and who she is. And I respect her. I genuinely care about who she is and where she’s going.”

The other was Anne’s mother telling me about her relationship with her second husband. “Whenever one of us comes home from work, we hug and kiss each other first, then the kids. And we make a point of spending at least fifteen minutes a day talking, just the two of us, no matter how busy we are. Because the kids are going to grow up and leave the house, get married, have kids of their own—and we need to still have a relationship when that happens! We are going to be together for the rest of our lives, so we have to invest in our marriage.”

Those two conversations helped shape my understanding of what relationships are about and see them as long-term propositions. It isn’t about being happy every day. There may be months or even years that are a hard slog. But with a solid foundation of love and respect, with shared values and goals, the investment of sticking together through those tough times pays off in the long run. Perhaps our shared experience of war also helps bind us closer together— certainly it gives us a more visceral understanding of what the other has experienced.

And here we are.

Brian still cycles through periods of depression that come on out of nowhere, leaving him low and joyless for weeks or months, which can only be kicked with a new round of medication. He still has headaches, sometimes short stabbing ones that double him over in agony for just a few minutes, others longer and lower, driving him into bed for hours. And his unpredictable bouts of PTSD symptoms still force him to carry his tiny vial of Valium to ward off anxiety attacks. We wonder if he will be hit with early-onset dementia (common for those with TBIs), if the shrapnel may shift, or if the future holds other physical or mental ailments due to the IED.

Doing research for this book, I tracked down Dr. Armonda, the neurosurgeon who operated on Brian in Baghdad. Brian hadn’t been sure the doctor would remember him, but Dr. Armonda recognized him immediately. It was powerfully moving to see him grinning ear to ear at Brian’s incredible recovery. It hadn’t occurred to me that battlefield surgeons often don’t know the ultimate prognosis of their patients, that their secondary trauma might be exacerbated by that lack of closure. While we talked about Brian’s journey toward healing, Dr. Armonda congratulated us on our successful marriage: “You know, only 20 percent of TBI patients are still married five years later.” The statistic shocked me. I knew the path we traveled had been hard, but had no idea so many other couples didn’t make it. Our marriage isn’t perfect. But it is solid.

Having children has actually—counterintuitively—improved our sex life. Before we had kids, it was easy to push it off to the next day if one of us was tired or busy . . . and then have the same thing happen again and again until seemingly all of a sudden it had been weeks. Some of the medications Brian was put on decrease sex drive, which could throw us off for months. And some of his symptoms, like the flattened affect, angry outbursts, and negative worldview, also made it much harder for me to feel sexually attracted to him. My hormonally induced shifting sex drive and changing body during and after pregnancy made me much more aware of how factors outside one’s immediate control can influence desire, and helped open new lines of communication between me and Brian about sex. We realized that having to juggle all our schedules meant we had to add sex to the mix or it could get lost entirely, so even if we’re not both in the mood when opportunities arise, we take them anyway, aiming for twice a week. There’s a good chance that the intimacy will spark arousal, and even if the time available or level of passion is constrained by circumstances, our relationship benefits from simply having regular sex—it reminds us that we are husband and wife, not simply parents and household partners.

Sometimes we still wonder what we want to be when we grow up. Neither of us is completely satisfied with where we are or what we do. I contemplate leaving RAND to work more actively in the veterans’ community. Brian is considering going back to school. We toss around small-business ideas. But both of us know that our vague itching to improve our lives even further is a clear sign of our profound privilege.

As the kids get older, we want to find new ways to volunteer. Getting involved in projects larger than ourselves and committing to our community has been an important part of our road to recovery, but having two young children has eaten into our available time. We are anxious to find new ways to connect.

Brian and I have sacrificed more than most for this country: a tiny fraction of our peers have served in Iraq or Afghanistan, compared to the large percentages of citizens who signed up to fight in WWII . And though significant numbers of veterans from today’s conflicts have come home with some type of physical or psychological wound, few have sustained the type of severe penetrating brain injury Brian suffered.

And yet.

We have lain wreaths on the graves at Arlington. We have seen those who have come home so profoundly injured that they will never be functionally independent. Our sacrifices pale to nothingness beside the grief of those families. We are living proof that for many struggling with physical and psychological wounds of war, there is a path back from the brink of despair to a meaningful new existence. Though it is a rough road, with the right support it can be navigated. All of us, as citizens, have an obligation to ensure that services are in place for those who need them. Brian and I hope that our example and our efforts ease the way for those still coming home.

We are blessed beyond imagining, being able to look back over the decade we’ve known one another, assess the ebb and flow of our relationship, and imagine where it will go as we move forward. The wars we fought, both overseas and here at home, may have shaped us, but they will not define us.

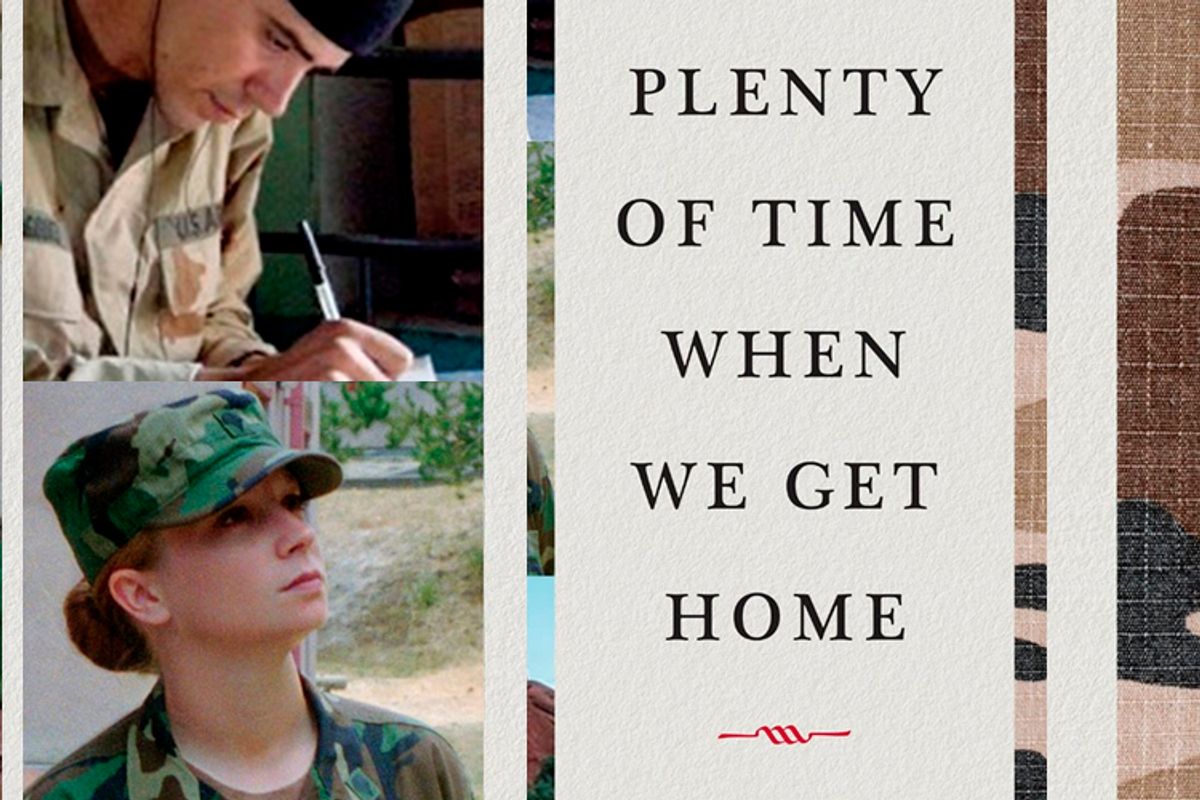

Excerpted from "Plenty of Time When We Get Home: Love and Recovery in the Aftermath of War" by Kayla Williams. Published by W.W. Norton and Co. Copyright 2014 by Kayla Williams. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares