LITTLE ROCK, Ark. — Because I wanted to see where the sidewalks and the city end, where development gives way to urban decay, I decided to go for a walk. When I walked, I walked to east Little Rock.

First there is the thoroughly gentrified River Market area, bustling with bars and banks, expensive restaurants and new construction. After that comes the Interstate 30 ramps; I am the only pedestrian. Then finally before me is a wide expanse of manicured and watered lawns, the benches and trees of the beautiful Clinton Library. It's there that east Second Street comes to an abrupt halt. You can't go through the Clinton Library to resume your trajectory on Second Street farther east without paying an entry fee, so instead you go around. The sidewalks are still wide on Third Street, the detour route of choice, and lead over to the Heifer International's giant campus -- like the library, another architectural wonder.

Strolling through Heifer's immaculate grounds, I realized that from this isolated center near downtown Little Rock, help goes out to the needy in dozens of developing countries -- a worthy and noble project. Yet when the sidewalks and lawns of Heifer's campus end -- just blocks east of the modern offices of the Chamber of Commerce, it turns out -- there is a stout and permanent barricade, as if to say "the east and the west of this city shall not ever meet."

If you trek back over to Second Street, you'll find that it has now resumed its course; but out here, having passed by the previous world of commerce and food and drink, another world comes into view: forgotten and desolate, made up of dilapidated houses and abandoned cars, scattered litter and empty streets. There are no sidewalks here. The atmosphere of neglect and abandonment is tangible, palpable. It is eerily quiet, and thoroughly depressing.

There are no sounds or traffic and the only perceptible smell is that of a decaying cat in a gutter on this hot mid-July day. What I see now before me is the invisible place that Michael Harrington wrote about in his book "The Other America," which began the War on Poverty. A war, it's clear to me, that we are still losing.

The unemployment rate in east Little Rock hovers at 16 percent. The poverty rate is north of 37 percent. Yearly income per capita is below $15,000 (or less than half the Little Rock average). The poverty rate is 164 percent greater than the Little Rock average. The estimated crime index here is 34 percent higher than the city average. The estimated property crime rate is 34 percent higher here. These statistics are about the same for south Little Rock, down past the Wilbur D. Mills freeway, which -- just as Interstate 30 does -- splits otherwise adjacent areas away from one other, generally on racial lines.

In the middle of this landscape, there is a Department of Human Services office. People go there -- the unlucky and invisible ones -- to apply for what once were called food stamps. Alternately in and out of fashion since its inception in 1939, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program ended along with the Great Depression, as the country geared up for World War II production. After that, an 18-year lull in research, reports and legislative proposals ensued. President Kennedy restarted the program in 1961.

The USDA’s idea for the first food stamp initiative is credited to various people, most notably Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace and the program's first administrator, Milo Perkins, who visualized America's poverty problem as such: “We got a picture of a gorge, with farm surpluses on one cliff and under-nourished city folks with outstretched hands on the other. We set out to find a practical way to build a bridge across that chasm."

The plan was to improve agriculture while at the same time improving the nutrition of poor Americans. The basics of the program have changed over time, but the theory remains the same: Those who cannot find jobs that pay enough to live need supplemental food assistance. Even still, you cannot live on food stamps alone, by any means. The benefits supplement what you already have. And the rules have changed so that there are hurdles. Now recipients must provide documents to prove that they are not trying to "game" the system, that they are truly needy. These documents are scrutinized. Fraud is rare.

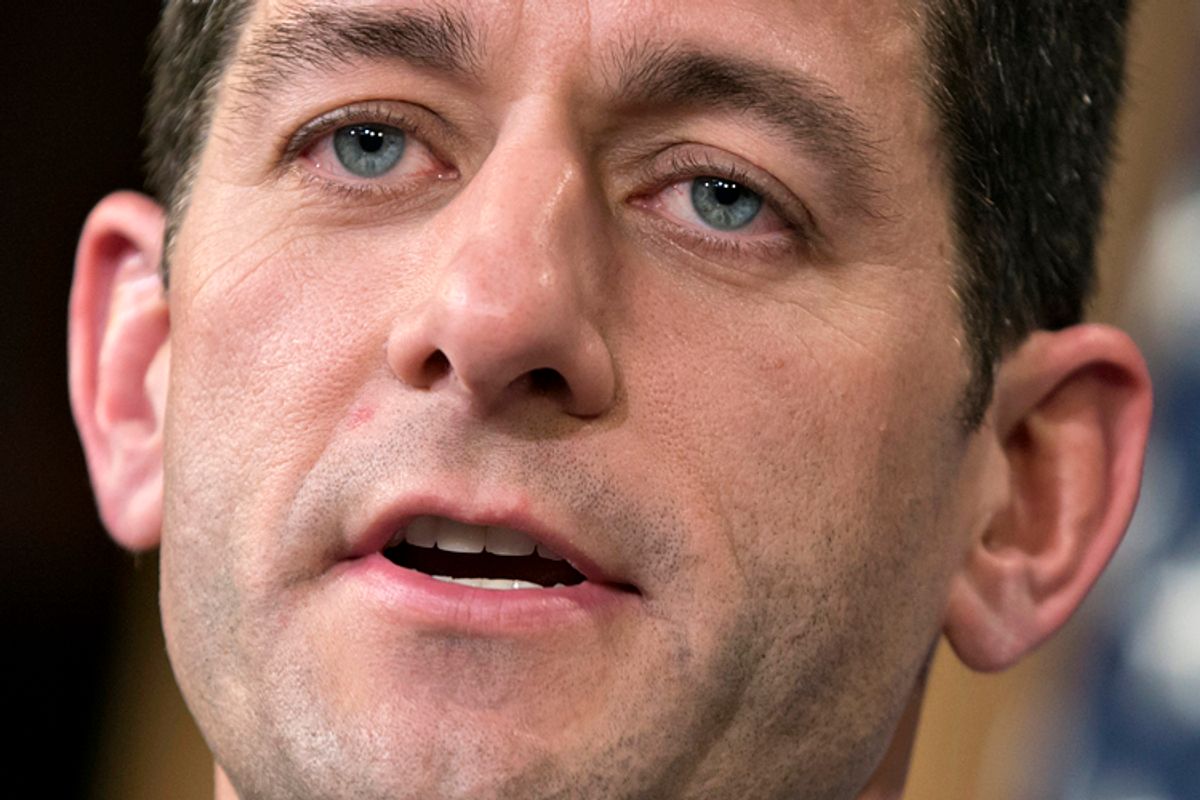

A phony food stamp war was declared by certain politicians in Washington last year (where, we absolutely must remember, it takes $1.4 million to be elected to a House seat). The leader of the crusade against poor Americans, Paul Ryan, has said that the social safety net is at risk of becoming a “hammock”; one that, one presumes, would have accommodated so-called freeloaders unworthy of government assistance. Mr. Ryan needs to take a walk on the east side of Little Rock.

Last year, a group of conservative House members conspired to strip SNAP funding from the farm bill it had long been tied to. In the process, food stamp spending would have been drastically reduced. Although some cuts to food stamps did make their way through Congress, the larger plot was eventually fought back.

Even still, the Republican Party, caught in the grips of Tea Party orthodoxy, fights tooth and nail to scale back other portions of the safety net: to undermine Social Security, to derail the expansion of Medicaid. Were they to ever, truly succeed in this pernicious agenda, the effect on places like east Little Rock is hard even to consider.

Ed Gray lives in Little Rock.

Shares