Stokely’s antiwar speeches and draft status combined to make him a powerful symbol of defiance, for both radicals and conservatives, of the increasingly controversial Vietnam War. Throughout the second half of 1966, politicians and bureaucrats urged military officials to draft Carmichael and send him to Vietnam even as he vowed to go to jail rather than fight. His bold antiwar posture garnered renewed controversy but also further praise, especially from college students who sympathized with words of fire directed against Lyndon Johnson. Carmichael defined the Vietnam War as a microcosm of the many ills plaguing American democracy. At first, he called for an end to the war. Later, he would call for America’s military defeat. Carmichael’s reputation transcended American borders, stretching into the political consciousness of black soldiers in Vietnam. The Baltimore Afro-American’s report of discrimination facing “tan servicemen” in Saigon featured black GIs who embraced Carmichael’s militancy. “We have manifested a 100-per-cent pride in being black,” explained one soldier. “We want to be black . . . even in Vietnam. Damn the civil rights bill. We want our constitution.”

Carmichael’s brilliant essay “What We Want” in the September 22nd issue of The New York Review of Books defined Black Power as a political philosophy born of deeply personal experience. He blamed SNCC for serving as an unwitting buffer between white society and the black masses, as racial interpreters who helped to maintain the illusion that American democracy required little more than reform. SNCC and other civil rights groups underestimated the depth of institutional racism, the jagged edges of democracy, and the deep-seated hostility of whites against even the appearance of black advancement:

For too many years, black Americans marched and had their heads broken and got shot. They were saying to the country, “Look, you guys are supposed to be nice guys and we are only going to do what we are supposed to do—why do you beat us up, why don’t you give us what we ask, why don’t you straighten yourselves out?” After years of this, we are at almost the same point—because we demonstrated from a position of weakness. We cannot be expected any longer to march and have our heads broken in order to say to whites: come on, you’re nice guys. For you are not nice guys. We have found you out.

According to Carmichael, blacks, disabused of blind faith in whites, could now embark on a political mission to transform the nation on their own terms. Black Power’s significance lay in its uncompromising assertion that blacks could independently define social, political, and cultural phenomena. This meant wrestling with the way in which race and class shaped hope, opportunity, and identity. SNCC’s time in the Mississippi Delta and Alabama’s Black Belt convinced its young organizers that power could alter the wretched socioeconomic conditions faced by black sharecroppers. Yet even this change, Carmichael admitted, would provide only incremental relief: “Ultimately, the economic foundations of this country must be shaken if black people are to control their lives.”

“What We Want” intellectually disarmed some of Carmichael’s fiercest critics and in the process announced SNCC’s chairman as a formidable thinker. For readers of The New York Review of Books, the essay was a revelation that easily transcended clichés surrounding black radicalism. “We won’t fight to save the present society, in Vietnam or anywhere else,” Carmichael concluded. “We are just going to work, in the way that we see fit, and on goals we define, not for civil rights but for all our human rights.”

Shortly after Carmichael’s essay appeared, CBS News broadcast on September 27 a special report, “Black Power, White Backlash.” Carmichael, wearing the African robe given to him by Guinean President Sékou Touré (via Jim Forman), spoke to correspondent Mike Wallace from SNCC’s Atlanta headquarters. Carmichael once again defined Black Power as an act of political self-determination and countered Wallace’s attempts to link the slogan to violence. “Now, I’m not concerned about the question of violence,” said Carmichael. “It seems to me that will depend on how white people respond. If white people, in fact, are willing not to bother black people because they are black, then there’s going to be no question of violence.” Carmichael described urban riots as “rebellions,” offering an alternative to Wallace’s “white backlash” thesis. From this perspective, waves of civil unrest in black communities reflected the depths of a social order created and maintained by white society. The cure for violence, he said, lay in black consciousness. Political self-awareness would lead to community control over housing and resources and turn ghettoes into thriving neighborhoods. “And the means you will use to achieve all of this?” asked Wallace. “Any means necessary,” replied Carmichael.

Offered the chance to speak directly to white America, Carmichael issued a stark indictment:

I would say, “Understand yourself, white man.” That the white man’s burden should not have been preached in Africa, but it should have been preached among you. That you need now to civilize yourself. You have moved to destroy and disrupt. You have taken people away, you have broken down their systems, and you have called all this civilization, and we, who have suffered at this, are now saying to you, you are the killers of the dreams, you are the savages. . . . Civilize yourself.

Two days after the CBS broadcast, Carmichael was the subject of a wiretapped conversation between Martin Luther King and Stanley Levison. National unrest disappointed King, who recounted his recent conversation with Whitney Young when both men contemplated resigning from their respective organizations, a thought Levison dismissed as insufficiently symbolic. The gubernatorial nomination on Georgia’s Democratic ticket of the openly segregationist Lester Maddox depressed King. He and Levison discussed Carmichael’s role in shaping contemporary political currents and jointly agreed “Stokely must be politically isolated.” They discussed how moderate civil rights leaders found Carmichael’s behavior appalling, suggesting that he be treated as a “black Trotskyite,” and blamed Maddox’s nomination on Carmichael. FBI informants reported that King had received assurances from Carmichael that same evening that he would temporarily halt Black Power demonstrations until after the mid-term elections. The accord formed part of a back-channel request from President Johnson to ease the pace of escalating racial tensions connected to civil rights demonstrations.

Carmichael spoke to a packed audience of Black Power militants in Detroit on Tuesday, October 4. At least fifty whites joined thirteen hundred blacks at Black Power theologian Reverend Albert Cleage’s Central Congregation Church. Cleage, along with attorney Milton Henry, who also spoke, represented the vanguard of the Motor City’s black militants—activists whose extensive political portfolios included establishing intimate alliances with Malcolm X that stretched back to the 1950s. Henry was a former air force lieutenant, and his political association with Malcolm X thrust him into the upper echelons of black political radicalism by the early 1960s, buoyed by keen business instincts that found him marketing black political radicalism through his own media company. Henry’s introduction paid tribute to Malcolm and Stokely while noting the historic vulnerability of radical black political leaders. “We need to erect monuments to our Stokely Carmichaels everywhere while we still have them” since “we didn’t do it to Malcolm,” said Henry with a tinge of personal regret overwhelmed by a cascade of applause that continued as Carmichael walked to the podium.

Before speaking, Carmichael paid his own tribute to Rosa Parks, whom he called his “hero” and who was now serving on Michigan congressman John Conyers’ staff. “Individualism is a luxury you can no longer afford,” Carmichael said in a speech that balanced his anti-Vietnam message with an indictment of the black middle class as racial poseurs who abandoned their less successful brothers and sisters in urban ghettos. Over repeated interruptions of applause, Carmichael touted the creation of cooperative stores, credit unions, and insurance companies as more humane an alternative to modern-day capitalism, applauded Muhammad Ali and Adam Clayton Powell as symbols of Black Power, and vowed to make black people recognize their own beauty, which they remained frightened of. “I’m six foot one, 180 pounds, all black and I love me,” said Stokely. “We’re not anti-white, it’s just that as we learn to love black there just isn’t any more time for white.”

Carmichael’s electrifying appearance at Central Congregation brought together two generations of civil rights and Black Power activists, offering a new genealogy of both movements. The presence of Parks, lauded as the spark of the Montgomery Bus Boycott and symbolic progenitor of the Civil Rights Movement’s heroic period, elegantly reflected the era’s ideological and organizational diversity. Cleage and Henry illustrated the often-times hidden passions and spectacular ambitions of a northern black freedom struggle that, in certain instances such as Detroit’s Walk for Freedom, converged with more-conventional civil rights demonstrations. Carmichael (whose business suit hinted at the civil rights movement’s lasting influence on him) represented the most unique political activist of his generation, having served on the front lines of southern civil rights demonstrations and northern Black Power insurgency. Stokely now served as a living bridge between civil rights and Black Power activists.

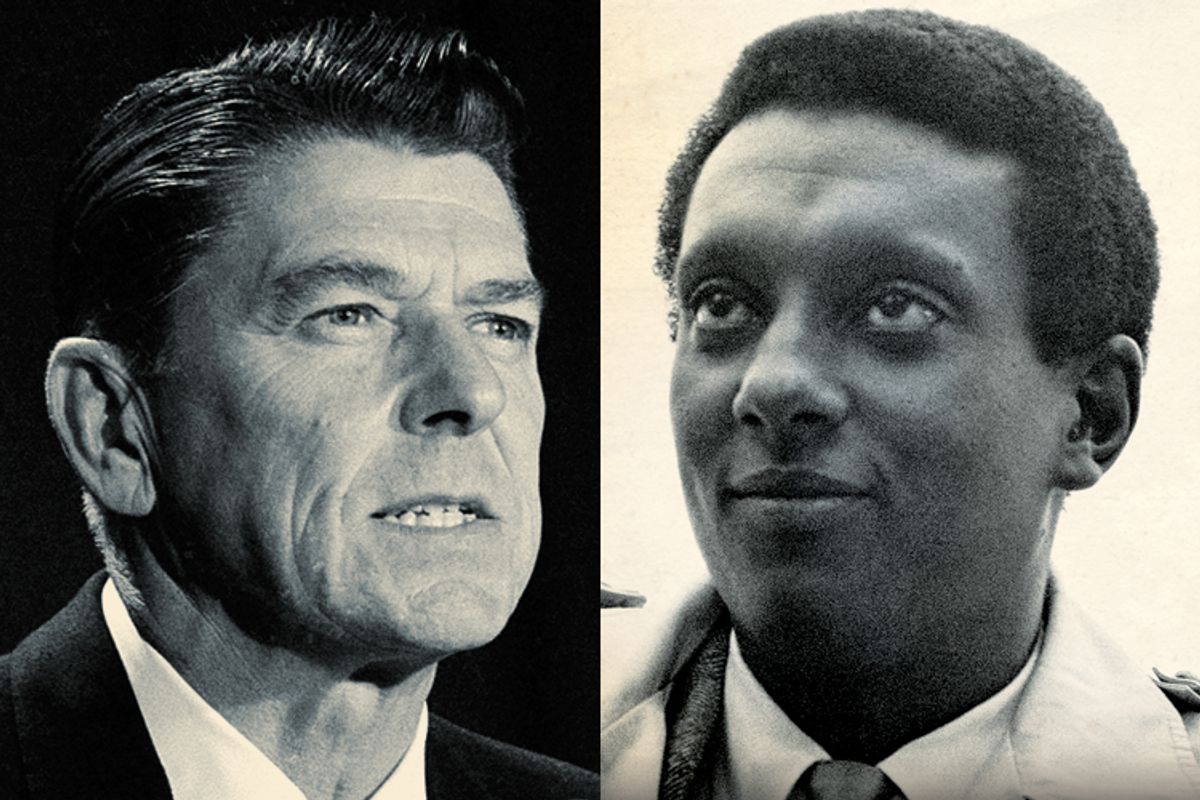

But moderate civil rights leaders were publicly opposing Black Power. In a manifesto statement issued on October 13, Bayard Rustin, A. Philip Randolph, Wilkins, Young, and National Council of Negro Women president Dorothy Height, but not King, signed a statement titled “Crisis and Commitment” denouncing Black Power. King’s signature was noticeably absent. Only in private would he discuss the issues raised in the statement. Meanwhile, in a New York television studio on The David Susskind Show, Carmichael dismissed those who blamed him for tipping primary election results in Georgia and catapulting Ronald Reagan to front-runner status in California’s gubernatorial race. “If I’m responsible for all of these elections,” he quipped, “SNCC wants me to run for president.” In Atlanta, reporters pestered King, conspicuously absent from the anti-Black Power screed, for comment on the entire matter before wrestling tepid words of support for Stokely that Friday’s headlines twisted into a whole-hearted endorsement.

In California, Reagan deftly exploited racial fears in the weeks leading up to the November election. Reagan’s outspoken criticism of Carmichael served as a prelude to his blood feud with the Black Panthers and enmity toward radical activism in general. On Tuesday, October 18, Reagan sent Carmichael an open telegram asking him to cancel an appearance at the University of California, Berkeley, that “could possibly do damage to both parties.” California’s embattled incumbent, Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, rejected Reagan’s overtures to join him in his request and accused his challenger of pandering to conservative voters and black militants. “Carmichael and his black power friends are doing everything they can to defeat me and elect Reagan,” Brown lamented. “They don’t want peaceful progress, they want panic in the streets and publicity. And Reagan serves their purposes by helping to give them both.”

If politicians were scapegoating Stokely, in private he was getting it from all sides at SNCC. His lecture and speaking fees were now SNCC’s main source of income and an invaluable organizational resource if properly harnessed. Though Carmichael rationalized his schedule as an example of political commitment to the movement, the constant attention and adulation he received in black communities fed his ego.

Things came to a head at a central committee meeting in Knoxville, during the weekend of October 22–23. On Sunday, Carmichael, in an Oral Report of the Chairman cloaked as a mea culpa, passionately defended his tenure. “Rhetorically, there have been a lot of mistakes made,” he admitted. Since the last central committee meeting, Carmichael had spent the bulk of his time up north, visiting experimental SNCC offices in New York, Boston, and Chicago. Carmichael suggested correctly that his rhetorical excesses jeopardized SNCC’s embryonic northern inroads and placed the group in an even more precarious political and financial state. But North and South were very different. “One of the problems we have in the North,” he lamented, “is that we do not understand political machinery.” Carmichael offered the rare but telling admission that, despite his considerable gifts, national leadership required new levels of political sophistication. Carmichael reported that across the nation, projects were in a state of disarray: Los Angeles and San Francisco offices moribund; Atlanta’s in flux; Harlem’s promising efforts at community control offset by opposition from Bayard Rustin and Whitney Young; Alabama in danger of having only one organizer, H. Rap Brown; and Mississippi sorely missing the leadership and presence of Cleve Sellers, who had as program secretary frequently traveled with Stokely and was no longer able to concentrate on local organizing. In a move that would have surely have made Jim Forman smile, Carmichael tasked the central committee with instilling unprecedented levels of organizational discipline, instead of merely assuming people were “working on our programs.”

Verbally chastised by Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, Faye Bellamy, future program secretary Ralph Featherstone, and others, Carmichael preached consensus by suggesting the central committee establish clear “guidelines” for his public speeches. Beyond petty jealousies and private grievances over Stokely’s celebrity, staff chafed against public perception that their new chair controlled them and grimaced each time his personal opinions ran ahead of, or contradicted, organizational policy. Chastened, he expressed regret for political transgressions and promised to halt his speaking tour after December 10 to focus on staff development and SNCC’s “internal structure.”

Efforts to contain Carmichael’s rhetorical escapades paralleled SNCC’s organizational crisis. Two-thirds of the group’s 135 members now operated in Atlanta or northern cities. The South’s remaining staff suffered from creeping disorientation over SNCC’s Black Power thrust, a feeling exacerbated by a lack of resources, apathy, and burnout. Efforts in Harlem, Philadelphia, and Chicago offered promising opportunities to transplant SNCC’s organizing prowess to cities but just as often invited new waves of official repression. The remainder of Sunday’s meeting broke along twin fault lines of ambition and dysfunction, resulting in plans to send a delegation to Africa in the New Year, assign a fundraiser to southern projects, and pay the rent for Atlanta staff by cutting salaries in half. Some of the proposals, most notably for establishing SNCC’s International Affairs Committee, would flourish amid organizational decline over the next two years but most would remain stillborn. Jim Forman urged the group to develop long-term political education programs, recommending a period of study to prevent growing apathy and political lethargy. Five and a half months into his chairmanship, Carmichael complained that it was “impossible” to serve the dual roles as “administrator and fundraiser,” already guessing that he would spend the rest of his tenure fundraising.

Carmichael struggled to fulfill his role as SNCC chairman even as acting attorney general Ramsey Clark and FBI official Deke DeLoach debated prosecuting him on federal charges. The FBI pressed Clark for wiretap surveillance of Carmichael, sensing an opportunity to corner the inexperienced AG. Clark refused the bureau’s request for telephonic surveillance, fearing a public relations disaster if news of the wiretap leaked, noting Carmichael’s reputation as a civil rights leader, and not wishing to risk future legal prosecution. Sensing DeLoach’s disappointment, Clark asked him if the bureau “would elaborate” on its reasoning for the Carmichael wiretap. DeLoach replied that director Hoover’s request came at the insistence of the president, who “wanted to make absolutely certain the FBI had good coverage on Carmichael.” Absent microphone surveillance, the bureau’s investigation remained hamstrung, and since Carmichael’s “activities and statements bordered on anarchy,” the FBI felt comfortable with the request. While the bureau had Carmichael’s Selective Service records, they had failed to procure his college files and required fresh intelligence regarding “where Carmichael was getting his money, whom he was taking orders from, whom he associated with, and his plans for the future.” Fearful of communist subversion in the black movement, the FBI imagined that Carmichael received direction from foreign outposts; it routinely investigated wild rumors and false sightings that connected the SNCC chairman to the Communist Party and related organizations.

The Carmichael wiretap request exposed a rift between Hoover and Ramsey Clark that would grow over the next two years. DeLoach’s efforts to box in Clark by leveraging the White House’s interest failed. Even as Clark took pains to relay a message to Hoover that he was not “deliberately delaying action on the Carmichael request,” he steadfastly refused wiretap approval. Clark’s political independence and reverence for civil liberties and the rule of law made him a political enemy of the FBI, whose forces he nominally led. Hoover considered Clark’s philosophy of “combating crime through an attack on poverty” both politically naïve and dangerous. As attorney general, Clark refused calls to arrest Carmichael on sedition charges and developed a thoughtful, deliberative political style that made him the rare White House official who balanced growing hysteria around Black Power, race riots, and social unrest with political restraint.

Justice Department officials debated Stokely’s fate on the same Thursday that he reported to a pre-induction facility in New York City. Carmichael’s fitness to serve in Vietnam would hinge on the results of his latest medical evaluation. Draftees, mostly from the working and welfare classes, fought the Vietnam War, on the American side, and the draft exemptions of celebrities were given particular scrutiny in the media. Stokely’s draft status ranked behind actor George Hamilton (who was dating a daughter of President Johnson) and Muhammad Ali as the public’s third-most popular Selective Service inquiry. After a preliminary interview with a psychiatrist, Carmichael arrived at St. Albans Naval Hospital in Queens for physical and mental tests. Carmichael’s vociferous antiwar speeches placed his 1-Y exemption (available for service in emergency, but exempt because of health or other reasons) under official scrutiny, but he refused to back down. On Friday, Carmichael returned for a final medical evaluation. After completing his exam, Carmichael departed the induction center’s rear entrance in a vain effort to avoid journalists. “I’d rather go to Leavenworth,” he told reporters, insisting that he would refuse to serve “on the grounds of my own conscience.” From the induction center on his way to a brief reunion with Mummy Olga in Harlem, Carmichael teased reporters that he wore tinted granny glasses “because they make me look non-violent,” joked with the cabdriver that all this media attention meant that “somebody must have stolen something,” and, once he arrived at his destination, wolfed down a plate of rice and beans and chatted with relatives. Determined to hail down a black cabbie on Harlem’s 125th Street to take him to the airport, Carmichael paused as a Puerto Rican taxi pulled up. “Close enough,” he said and hopped in. At Kennedy Airport, before boarding a flight to California, Carmichael repeated his promise to go to prison rather than Vietnam.

The interest of the FBI and White House in Stokely’s draft status surpassed that of journalists, politicians, and the general public. Naked political calculations fueled the White House’s secret request to the FBI in September concerning Carmichael’s Selective Service status. The FBI responded three days later, furnishing sensitive information deliberately withheld from Ramsey Clark. The confidential records revealed that Carmichael’s first pre-induction exam on January 21, 1965, resulted in his draft status reclassification from 1-A to 4-F, which rendered him medically ineligible for service. The evaluating psychiatrist misidentified his civil rights activities as taking place in CORE rather than SNCC but concluded that his arrests revealed no inherent pattern of antisocial behavior. Disqualified for medical reasons, Carmichael took a second physical examination a year later, on February 14, 1966. “Has had two additional episodes of decompensation,” the examination noted, “in the past following the shooting of two of his friends.” The “decompensation,” or paralytic nervous breakdown, followed the killings of Jonathan Daniels and Sammy Younge. Both incidents burdened the usually self-assured Carmichael with bouts of inconsolable grief and a sense of helplessness, which he overcame through organizing. The chief medical officer of the induction center gave Carmichael a “Y” symbol following this second examination, making him eligible for military service in times of war. They suggested his status be re-evaluated and updated after one year.

At the University of California, Berkeley, on Saturday, October 29 with his pre-induction physical weighing heavily on his mind, Carmichael delivered his most important antiwar speech. This galvanic address, carried by newspapers across the nation, made him America’s leading critic of the Vietnam War. He arrived at Berkeley with better antiwar credentials than Martin Luther King. The speech marked a crucial turning point in antiwar activism among white radicals in the New Left who organized the conference. It also showcased Carmichael’s complicated relationship with white activists. Three months earlier, Carmichael had brokered the release of a joint antiwar statement with SDS president Carl Oglesby. Now, his effective linking of Black Power insurgency to the war in Vietnam offered white activists a new entrée into the black movement if they dared. Carmichael’s presence in Berkeley explicitly invited whites to participate in a larger anti-imperialist movement that SNCC had sketched at the beginning of the year in its controversial antiwar statement. But, as usual, Stokely did so on his own terms. He admonished student activists for their reticence in opposing the draft with the imposing authority of an icon who had defiantly proclaimed his draft resistance before Muhammad Ali, but he offered no specific organization vehicle or interracial alliances to facilitate this objective. Following Carmichael’s speech, SDS would take matters into their own hands, organizing a vast array of campus antiwar activism. Over the next two years, the Black Panthers would offer SDS and the wider New Left access to participate in the broader revolutionary struggle that Carmichael and SNCC first outlined. Despite his reluctance to actively work with white radicals, Carmichael’s bold antiwar rhetoric provided the intellectual and political contours for whites to engage in a global assault against American imperialism. Stokely’s increasingly hard public line against the possibility of interracial alliances obscured his continued personal and professional relationships with whites. Away from the media gaze, he followed his Berkeley speech by attending a party in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, where he openly consorted with white friends and intimates in a manner that contrasted with his public stance. Carmichael enjoyed the sexual freedom, casual use of marijuana, and social pleasures that both the times and his celebrity status offered. Before fame, Stokely possessed the charm and charisma to attract the attention of a variety of women. After, his opportunities and appetites increased.

At Berkeley, Carmichael’s discussion of Black Power’s relationship to larger failures of American democracy soared into the high ground of rhetorical eloquence as it plumbed the racial and historical depths of black life. Standing at the podium of the Greek Theatre, scanning the overwhelmingly white crowd, Stokely might have rationalized his presence at Berkeley as a kind of missionary work, since, as he remarked at an earlier press conference, “it is white institutions which perpetuate racism within the community.” In California, Stokely entered the ranks of black America’s iconic leaders, joining a pantheon that stretched from Frederick Douglass’ abolitionism to Ida B. Wells’ turn-of-the-century anti-lynching campaigns, through the controversy between Booker T. Washington (accommodation) and W.E.B. Du Bois (activism), the Marcus Garvey movement, and Malcolm’s and King’s parallel and morally charged political and religious crusades.

Dressed in a suit and tie, he resembled a campaigning politician. Carmichael’s conservative attire contrasted with the radical themes he preached in a clipped accented voice. Like an itinerant evangelist, Carmichael turned the Greek Theatre into a mass political meeting that took on the energy of an outdoor religious revival. He diagnosed America’s rulers as sick with the disease of racism. Before the biggest audience so far in his speaking career, Carmichael defined racism’s uncanny influence on every aspect of American life, one that he challenged Berkeley students to dismantle. “A new society must be born,” he thundered. “Racism must die. Economic exploitation of non-whites must end,” said Carmichael. “Martin Luther King may be full of love, but when I see Johnson on television, I say: ‘Martin, baby, you have got a long way to go to accomplish anything.’”

The great contradiction of the civil rights movement was that although whites were “the majority” and thus accountable for “making democracy work,” blacks inevitably bore the burden of this responsibility. Blacks faced death on the racial front lines of the South even as most whites recoiled from such sacrifice. “The question,” according to Carmichael, was, “how can white society move to see black people as human beings?” In hundreds of talks over the next year he would hone this theme into a dazzling stump speech that imagined novel connections between race and war and found intimate kinship between Black Power and American democracy.

Carmichael sounded like a university professor: “The philosophers Camus and Sartre raise the question of whether or not a man can condemn himself. The black existentialist philosopher who is pragmatic, Frantz Fanon, answered the question. He said that man could not.” Born in Martinique in 1925, Fanon settled in France as a young man and became a psychiatrist. During the French-Algerian War, he supported the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale (FLN). His book, The Wretched of the Earth, an exegesis on revolutionary violence’s powers of renewal, partially obscured a radically humanist philosophy that implored oppressed people the world over to search for new forms of humanity free of racial and economic exploitation. Translations of Fanon’s French-language books afforded him a global following that ran past his premature death from cancer in 1961 at age thirty-six. Media depictions of Carmichael invariably portrayed his temperament as running hot, ignoring the cool side that enjoyed precise intellectual and philosophical discourse.

Carmichael implored those in attendance to use their individual will to form a collective barrier against escalating war. Echoing Sartre, Carmichael criticized national political leaders who made war instead of peace. “There is a higher law than the law of a racist named [Secretary of Defense Robert] McNamara,” said Carmichael, “a higher law than the law of a tool named [Secretary of State Dean] Rusk, a higher law than the law of a buffoon= named Johnson—it is the higher law of each of us.” Waves of applause overtook his defiant roll call of White House officials escalating the Vietnam conflict. “We can’t move morally against Lyndon Baines Johnson,” he contended, “because he is an immoral man who doesn’t know what it is all about. We must act politically.” He challenged his student audience to question the basic assumptions about American democracy and join SNCC in exposing “all the myths of the country to be nothing but lies.” Carmichael reveled in highlighting America’s moral and political failures even as he indicted white liberals as feckless and white students as unsophisticated. “It is white people across this country who are incapable of allowing me to live where I want to live—you need a civil rights bill, not me,” he said. “I know I can live where I want to live.” This last line drew a burst of applause and helped to introduce a larger discussion of white privilege that became the core of the speech:

The question then is how can white people move to start making the major institutions that they have in this country function the way it is supposed to function. That is the real question. Can white people move inside the old community and start tearing down racism where in fact it does exist—where it exists. It is you who live in Cicero and stop us from living there. It is white people who stop us from living there. It is the white people who make sure we live in ghettos of this country. It is white institutions that do that. They must change. In order for America to really live on a basic principle of human relationships, a new society must be born. Racism must die. The economic exploitation of this country on non-white peoples around the world must also die—must also die.

Hysteria greeted Carmichael’s Berkeley speech. Governor Pat Brown and his Republican challenger, Ronald Reagan, both decried Carmichael’s appearance although each knew that it boded well for Reagan, already riding a wave of popularity buoyed by “white backlash” against black militancy. In Washington, Ramsey Clark received a fresh batch of requests from congressmen to prosecute Carmichael for promoting draft evasion. The Mississippi senator and arch-segregationist James Eastland telegrammed Clark that Carmichael’s “reckless and inflammatory speeches” promoted “acts bordering on treason.” But Stokely found at least one high-profile supporter, who intensely watched his every move despite an outward pose of studied disinterest. At a press conference in Norfolk, Virginia, following a sermon that warned against racially separate paths to power, Martin Luther King defended Carmichael’s antiwar posture, telling reporters he would be the first to support an individual whose political actions were motivated by a call to conscience.

Excerpted with permission from "Stokely: A Life," by Peniel E. Joseph. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2014.

Shares