Astonishing as it may seem — and despite plenty of evidence to the contrary — some people still lob the “cookie-cutter” insult at university MFA programs in creative writing. They go on alleging that schools like the University of Iowa suck in idiosyncratic talents and extrude them out the other end as identically tasteful yet lifeless poker chips stamped with the image of Raymond Carver. So, first things first, we should all thank Chad Harbach for kicking that particular can a lot farther down the road.

Harbach, author of the bestselling novel “The Art of Fielding” and a founding editor of the journal n+1, produced an essay four years ago that broke through the usual foggy, high-minded rhetoric surrounding the writing process to lay out a grounded, practical view of the economics: “MFA vs. NYC.” Writers need to eat and pay rent, and nowadays, if they don’t want to take a day job, then they’ll need to earn a living either by selling their books (plus the occasional bit of journalism) or by teaching. A new book-length anthology of essays, “MFA vs. NYC: The Two Cultures of American Fiction,” kicking off with Harbach’s original piece, explores the institutions in which writers make a living and the cultures that arise from them.

Much excellent criticism has been published recently in response to this book, but like most discussions of the topic, they focus on how the contrast between the government-supported economy of university fiction programs and the market-driven economy of New York publishing affects writers. That makes sense, but it’s not the whole story. The MFA-NYC divide (a split that is promiscuously crisscrossed by authors every day, as Leslie Jamison observed in what is perhaps the most insightful review of the book, for the New Republic) also affects the rest of us by shaping the books we read.

As a reader, I confess, I lean toward the NYC camp. Still, MFA programs have produced much great work. George Saunders, who got an MFA, teaches MFA students and contributes an essay about the experience to “MFA vs. NYC,” is a living refutation of the old Carver canard. Many of the authors whose books I hungrily anticipate and devour are veterans of MFA programs.

Nevertheless, I do believe there’s a serious and seldom discussed flaw in the workshop model. The problem is, it’s also the best thing about the workshop model: specifically, that it provides young writers with not only the opportunity to be surrounded by people who care deeply about literary fiction (or nonfiction) but also with the chance to have their work evaluated by such people. It is in MFA workshops that an aspiring artist can enjoy what Harbach describes as “the minute, scrupulous attentions of one’s instructor and peers.”

Some rebellious souls might find this intrusive, while to other more sensitive ones it might sound traumatic. The real problem is that workshopping can never be harsh enough. MFA programs create a bubble for the writers who enroll in them, but what these writers are protected from isn’t either the blistering reader reviews of Amazon or the swashbuckling critical crusaders of the legit press. Instead, pretty much by definition, the workshop world fails to prepare writers for what they will almost certainly face outside it: indifference and silence.

We live in a culture that doesn’t particularly care about books and authors, and that cares even less about literary fiction. There are bustling communities that spring up around projects like NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) and the self-publishing scene, but they’re populated by folks, writers to a one, who really just want you to read their books, not vice versa.

Unless an MFA student has prior experience of this daunting state of affairs, he or she is liable to take for granted the most unnatural aspect of any workshop program: its guarantee that a roomful of people will read and pay close attention to your work. No one — possibly not even their own editors, should they be lucky enough to publish traditionally — will ever scrutinize the work of these writers as closely as their fellow students and teachers.

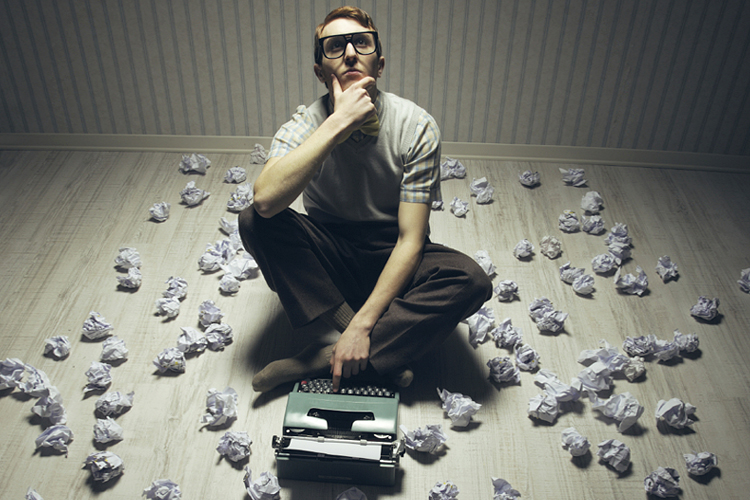

How does this affect their work? To judge by the complaints I’ve heard from many a writing teacher, the result, all too often, is fiction that falls short in the one area where no work of fiction can afford to fail: It’s simply not interesting. Even if these teachers tell their students, as any good writing teacher should, that they must seize a reader’s attention from the very first sentence, an environment in which one’s readers have no choice but to go on reading is not the best place to learn how to do this. It’s not that MFA instructors persuade their students to produce artful but boring work. To the contrary: They’re as bummed out about it as anyone else. Rather, this unfortunate blind spot is baked into the workshop method.

Whenever I’m asked to speak to a class of MFA students about the reviewer’s job (it happens every so often), I bring along my iPad and show them a photo of the stack of books I received in that day’s mail. It’s typically anywhere from 20 to 30 titles. That’s what I get every single weekday, and it pales in comparison to the stacks and tables of books that greet a civilian reader when she steps into her favorite bookstore. Most of these students fantasize about being published by the houses that send me these review copies, and in an ideal world, each of those titles would receive lengthy and patient consideration. Nobody lives in that world. The decision to read or not to read will likely be made on such ephemera as cover art or how appealingly the flap copy describes the premise, and an author is lucky if a reader takes the time to read her first page. Nobody owes a writer more than that if the first page doesn’t deliver.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t great novels that “start slowly,” only that nowadays settling for a slow start will likely doom a book to going unread, and no one can know how great it is if they don’t read it. Strong reviews might persuade readers to persevere, but only if the reviewers themselves are willing to push past an opening that lacks drama, conflict and a central character who wants something and makes some effort to get it. Style, when it comes to MFA grads, is usually less of a problem, but style alone is almost never enough to carry a story. For my own part, I simply don’t have time to read more than a chapter or two before deciding whether a book is worth my while, and even if, as rarely happens, I resolve to keep going, I’ll be ever aware of incentives to stop — incentives in the form of all the other books I could or should be reading instead.

Most new books are not especially good, and so, like most readers, I start them with the eminently realistic expectation that I probably won’t like them. A trusted recommendation or a solid authorial track record might up my hopes, but even that amounts to a tiny boost. It is the author’s first responsibility to persuade me, and the rest of the world’s readers, that he or she deserves our attention and our time. Given the hysterical narcissism and self-righteous pomposity to which the profession is so often prone (and I say this as an author myself!), that might just be the toughest lesson of all.

Further reading