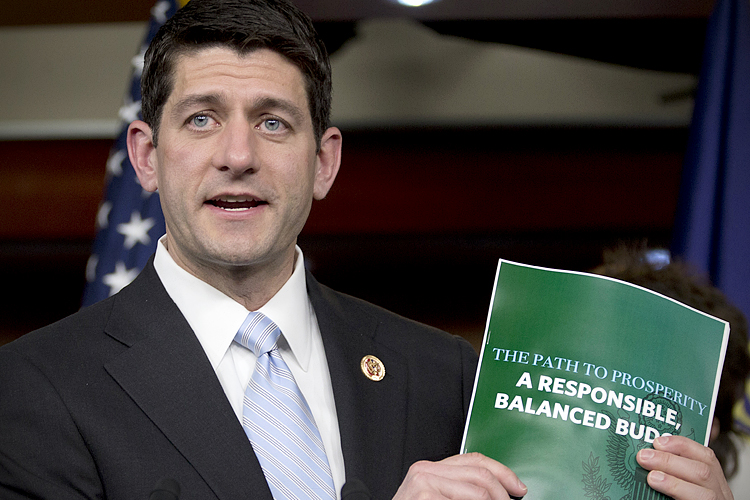

Poverty is back in the news, for several reasons. The first is the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 “War on Poverty” speech. In addition, Republican congressman and 2012 vice-presidential candidate Paul Ryan has released a much-criticized report about federal poverty programs. In 2012 the Romney-Ryan ticket suffered from Mitt Romney’s dismissive comments about the “47 percent” and conservative caricatures of the poor as welfare-dependent moochers and “takers.” Ryan’s attempt at a version of what George W. Bush called “compassionate conservatism” appears to be an effort at rebranding the right as something other than an alliance of Have-Lots and Have-Somes against Have-Nots.

Public debate about poverty typically focuses on the causes of poverty, rather than the cures. The causes of poverty are many and various. You may be poor because you are the child of poor parents; or because you grew up in an economically distressed urban or rural region; or because you were bankrupted by unexpected medical bills; or because you lost all your money gambling on imaginary real estate in “Second Life” (this actually occurred, in a case of which I know). Because poverty has multiple causes, policies must be equally numerous, if the goal is to avert or prevent poverty in the future.

But it’s not necessary to avert or prevent poverty in the future in order to cure the poverty that already exists in the present, for whatever reason. Let me illustrate this point with an example. The treatment of victims of gunshot wounds in the emergency room may be identical — even though one gunshot wound was caused by a shooting in the course of a robbery, another by a failed suicide attempt and a third by reckless play with a firearm. Doctors and nurses can treat the victims of the gunshot wounds now, while leaving others to propose better policing, better suicide-prevention counseling and better firearm safety training in the future.

Fortunately, drastically reducing existing poverty in the U.S. is not a difficult intellectual problem, even though it is a difficult political problem. With sufficient political will, we could slash existing poverty in the U.S. very quickly, while simultaneously trying to prevent as much poverty as possible in the future. Some public policy problems, like averting global warming or regulating shadow banking, are incredibly complex. By comparison, antipoverty policy is simple.

We know exactly what we need to do to radically reduce poverty in America. We know that it could be done, and we know how to do it, because many other First World democracies have slashed poverty already.

Among developed nations, the U.S. is an outlier in having a high proportion of its population living in poverty. Among the 34 member nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in 2010 on average 11.1 percent of the population suffer from “relative income poverty.” In the U.S. , however, the number is 17.4 percent. Among developed countries, only Chile (18%), Turkey (19.3%), Mexico (20.4%) and Israel (20.9%) have more of their people living in poverty, according to the OECD.

The low-poverty nations tend to be Scandinavian countries like Sweden (9.1%), Norway (7.5%), Finland (7.3%) and Denmark (6.0%). Some on the right argue that it is wrong to compare small, relatively homogeneous countries with a giant, pluralistic, continental society like the U.S. Others argue that the English-speaking countries as a whole are willing to tolerate more poverty and inequality than the Nordic social democracies.

The numbers don’t support these arguments. Among the most populous Western states are France (7.9%) and Germany (8.8%), both of which have around half as many people in poverty as the U.S., notwithstanding their own growing immigrant populations. And while all English-speaking countries tend to be less statist than continental European societies, all of the other anglophone nations have considerably less poverty than the U.S., including Australia (14.4%) and Canada (11.9 %). Indeed, three English-speaking countries — Ireland (9.0%), the UK (10.0 %) and New Zealand (10.3%) — have fewer citizens in poverty than the OECD average in 2010 of 11.1%.

How do other countries do it? They don’t necessarily have fewer poor people to begin with. According to an OECD study, with respect to “pre-tax, pre-transfer” poverty, the U.S., at 13, ranked in the middle of 26 high-income nations. When it comes to “post-tax, post-transfer” poverty, however, the U.S. was nearly the worst, second only to Israel.

The difference is entirely the result of government social spending on the poor — mostly in the form of transfer payments, like public pensions, unemployment insurance, child subsidies and/or wage subsidies. Many other developed democracies start out with lots of poor people, just like the U.S. But the countries with big welfare states remove most of them from poverty. The American welfare state does lower the poverty rate — but not enough. The American welfare state is way too small to be effective in doing its job of lowering poverty.

We know, then, how to slash poverty in the U.S. It’s very easy. All we have to do is expand the American welfare state, not necessarily to Swedish levels, but at least to Canadian or British levels. If we restrain public and private health cost inflation, by adopting medical price controls (“all-payer regulation”) of the kind used in most other democracies to prevent price-gouging by pharma companies, hospitals and doctors, we can pretty much end poverty in America very quickly.

A progressive fantasy? Well, not exactly. Yes, most American progressives would embrace much higher social spending. At the same time, many on the American left would prefer to pay for it with steeply progressive income taxes.

But the countries with really generous welfare states and social insurance systems, like those of Scandinavia, do not pay for them chiefly or solely with “soak-the-rich” income taxation. Progressive income taxes are part of the mix — but as Peter Lindert has pointed out, broad, relatively regressive taxes that fall on the middle class and working class, such as payroll taxes and the value-added tax (VAT), a consumption tax, are necessary to fund governments that take a bigger bite out of a nation’s GDP without inducing capital flight — or even capitalist flight.

Ironically, it is American conservatives rather than American progressives who favor a national consumption tax (even as some on the right oppose a value-added tax, which is by far the most efficient and familiar way to tax consumption). “Grand bargains” are usually bad ideas, but here’s a good one: We could slash poverty in the U.S. by means of “progressive” levels of social spending, funded in part by a “conservative” national consumption tax.

As an intellectual exercise, then, radically reducing poverty in America is extremely simple and non-controversial, at least among experts (genuine, scholarly experts, not paid propagandists at conservative and libertarian think tanks). All we have to do to radically reduce poverty from all causes in the U.S. in the near future is to increase government spending, raise taxes and increase regulation (all-payer medical price regulation).

Merely to state it like that is to suggest the political difficulty of translating this simple and straightforward policy agenda into reality. Between anti-tax Tea Party fanatics and cowardly Democrats terrified of being called “tax-and-spend liberals,” there is no chance of substantial reductions of American poverty in the near future. But this intellectual exercise is still worthwhile, for two reasons.

First, it allows us to understand that most of the people who talk about poverty in the U.S. are not actually talking about reducing poverty right now. They are focused on preventing poverty in 20 or 40 or 60 years, by means of preschool programs, or family therapy, or regional economic development, or whatever. Those are all fine and good. But because the experts and politicians and pundits talk almost exclusively about averting future poverty, rather than reducing present-day poverty, most Americans do not realize that present-day poverty, whatever its cause, really could be quickly reduced — if there were the political will to do so and to pay the necessary taxes.

This intellectual exercise is useful for another reason. It allows us to distinguish those who are serious about reducing poverty in America from charlatans. It is impossible to substantially reduce poverty in the U.S. without spending a lot more money on the poor and perhaps the middle class and paying for that spending with much higher taxes. Anyone who claims otherwise is, by definition, a fraud. Conservatives who claim that they know how to reduce poverty without raising spending and taxes are either ignoramuses or conscious con artists. And so are timid centrist Democrats who sound progressive, but whose actual proposals for addressing poverty are nothing more than teeny-weeny itty-bitty tweaks to the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) or the child tax credit.

This is not rocket science. The U.S. can reduce its post-tax/post-transfer poverty rate from 17.4 % at least to the OECD average of 11.1%, if not the Danish level of 6.0%. But doing so will cost money. Lots and lots of money.