"What if the immigrant never finds a new place?” Marlon James’s words haunt me. Often I wonder, can words be that new place? For me, writing has been a replacement home, a replica of all that was lost in service to a nomadic lifestyle. Much of this recouping and reassembly has been about Iran, using my fading memories of people and places as refurbished landscapes for my stories. As I write this, I am keenly aware of how many “re” words I’ve just used. Replacement. Replica. Recouping. Reassembly. Refurbished. What I’m building will never equal the original—my home, a village in Iran, a gaggle of family, a turmeric-stained cavern of a kitchen cradling my grandmother’s familiar body, a place where I belong without question.

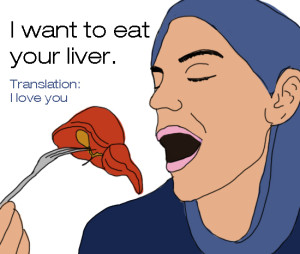

And yet, in at least one respect, the replica that I’m creating is more nourishing. My grandmother, like all village women of her generation (and city women too—and city men for that matter—and doctors, lawyers, teachers, and me), used to throw around funny little sayings, Iranian folk wisdom going back thousands of years. These idioms are so engrained in my native language that we don’t even think about them. They exist beyond the realm of cliché, in a place where the syllables that make up a saying are so tightly welded together that they can’t be pried apart, back into component words with separate meanings. When we want to show deep affection, to our lovers and children, we Iranians no longer say I love you. We say May I be sacrificed for you, or the far more dramatic (and therefore more appealing) I want to eat your liver. No one considers the individual words in such declarations—they don’t conjure the image of a man feasting on the liver of his beloved. The sayings have been stripped of their literal meaning so entirely that the only way to revive them, to experience their drama and intensity, is through translation or reconfiguration. In a recent song by an Iranian rap star, for example, the singer forces the listener to pry apart and absorb the actual, literal meaning of I want to eat your liver by inserting a single word, raw, right in the middle of the declaration, then repeating it. I want to eat your raw raw liver. That is the only way to remind the average Iranian what the phrase actually means: to confront them with its hyperbole.

In my novel A Teaspoon of Earth and Sea, which was written in English and translated into fourteen languages, I made liberal use of these sayings in creating the voices of four older village women who mutter and opine and worry in idioms. In translating each phrase into English (and watching them be translated into other languages, though my involvement was limited to clarification and approval of slight variations), I had to strip each idiom of its connoted, cultural meaning in my own mind (e.g., it’s difficult for a Persian to think of I want to eat your liver as anything other than I love you, especially since modern speech has shed a few of its syllables so it sounds more like I want your liver). Then I rebuilt the expressions using precise images (e.g., we are talking about eating a liver, not admiring one).

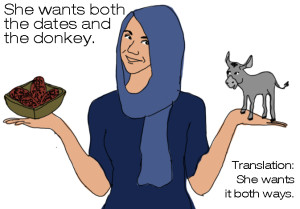

Often I added meaning by explaining the expression’s cultural history or by using it in a perfectly matched context—moments so well suited that I could pretend my characters invented each saying. For example, one of the village women tells my protagonist, Only die for someone who at least has a fever for you, at a time when another girl watches her lover executed. For this saying, in order to make the meaning absolutely clear, I added the word “only,” though it doesn’t appear in the original saying. To illustrate further, instead of just saying He wants both the dates and the donkey, I might create a parallel: He wants both his village lover and his fancy books. He wants both the dates and the donkey. While at first this process seemed inauthentic, the exercise of trying to make the idiom work in English, to provoke precisely the same emotion, the same level of intensity, humor, and delight, by conjuring the very same smells and sounds, brought my native language to life for me. It placed me right back into that village, recreating in my imagination the atmosphere of a home lost to me after two decades in exile.

My interest in Iranian sayings started with a letter, posted as a joke on some Iranian website. It’s a transcript of what I assume is a real letter written in English by a disgruntled Iranian worker to his American manager in the 1950s or ’60s. It begins, “Dear Mr. Hamilton, I am your servant… I am writing to you because of all the ways the handle of the knife has reached my bone. My hands grab your skirt…” and so forth. The letter is no more than a string of charming idioms translated clumsily and verbatim, one after another, with no explanation or context. To American ears, the resulting communication is hilarious, but it makes a strange kind of sense—the employee claims that “the handle of the knife has reached my bone” and then he explains his distrust of his brown-nosing coworker. One can easily gather that the saying connotes deep frustration to the point of physical pain. For weeks, the letter enraptured me—I could picture the man who wrote it. I knew precisely what he wanted. He wished for his rival to be fired and for the American boss to become his ally, though he only hinted at it. After that, I dove into a search for more of my favorite sayings from childhood, many of which go back to ancient Iran. It was a transformative step for my story; in the end, it was the salt that gave my novel its flavor.

Below I offer some examples, grouped in the four categories that I found most charming and easiest to replicate in English (as did my translators), because they go beyond Persian culture to the human basics—the good stuff we all share.

(poking fun at religion)

Mocking organized religion crosses all kinds of borders. Everyone does it, even in devout cultures, even despite deep respect for those caricatured. Iranians have managed to make mocking the clergy an art form, which is wonderfully brave given their theocratic government. The most obvious example of this is a fictional cleric called Mullah Nasruddeen. Stories of this bumbling mullah are used to deliver morsels of wit, wisdom, and advice all over Iran. In a famous story, Mullah Nasruddeen borrows a pot from his neighbor. The next day he returns it with a smaller pot inside and says, “It reproduced.” Delighted, the neighbor accepts. This interaction repeats the following week. Then the mullah borrows the pot a third time, but he never returns it. When the neighbor comes looking for it, the mullah says, “If it can reproduce, it can die.”

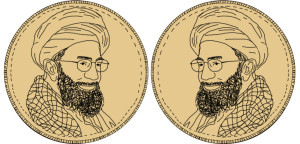

Beyond Mullah Nasruddeen stories, mullah idioms are merciless and plentiful in Iran. He’s as one-sided as a mullah’s coin hardly needs translation, though I did change it a bit. The original was he’s like a mullah’s coin—because, well, every Iranian knows about mullah’s coins, don’t they? I also edited the far more vulgar, his pockets are sealed tighter than a mullah’s ass. The original was only His pockets are like a mullah’s ass. I thought it safe to assume that the cautious wink-wink of the original saying would be lost on the Western reader. Though some are more vague and oblique than others, what these idioms have in common is an implied attitude that at their worst, mullahs represent stupidity, blind dogma, moral superiority, repression, and greed.

(village life)

While village life may not be a universal experience, most modern civilizations have histories rooted in agriculture. In Iran, camels and donkeys tend to be a major part of that life. Funny enough, I found this category easiest to translate for Western readers. After all, how many possible uses are there for a donkey? And readers are often delighted by the simple charms of rural living. And so, I seasoned the tongues of my village women with these direct and altered translations:

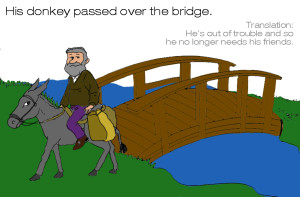

Don’t ride a camel bent over (don’t try to be discreet when doing something obvious. In the Farsi, the saying is You can’t ride a camel, bent bent. I changed it for absolute clarity). He wants both the dates and the donkey (an easy, direct translation: he wants it both ways). His donkey passed over the bridge (he’s out of trouble and so he no longer needs his friends). I don’t want camel’s milk and I don’t want an Arab in the house (I don’t want this unpleasant thing that is offered, whatever it may be, as much as I don’t want camel’s milk or an Arab in the house—this is a more obscure saying that many Iranians no longer know or use).

(food)

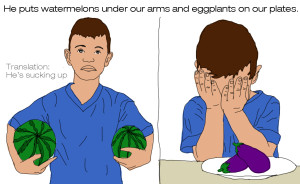

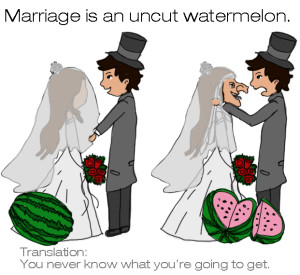

Watermelons, eggplants, pomegranates, pistachios, rosewater, and rice are staples in the Iranian diet. They have been for centuries and so they appear often in the oldest idioms. Ironically, this category was the hardest to translate into English because the American attitude to food is so far removed from the Iranian one. How is an American to know which foods are considered luxuries, which are considered daily necessities, and which combinations are cursed or lucky? Whatever your background, it seems a mean gesture to fill someone’s sugar bowl with salt. But an American would never guess that it’s also a curse. So, when I put the following idioms in the mouths of my characters, I often added hints through dialogue or a few words of careful exposition: He puts watermelon under our arms/eggplant on our plates (He is sucking up. The original version is Don’t put watermelon under my arms). Marriage is like an uncut watermelon (you can’t see what you’re getting until you’re committed). For the latter, I presented the saying from the point of view of a mother offering advice. To drive her point home to the young woman she’s advising, she articulates a version of the words in the above parentheses.

(pure melodrama)

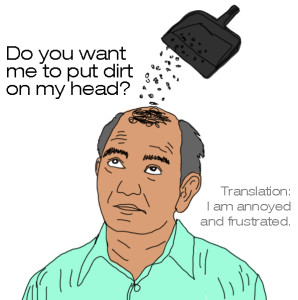

Exaggeration is a gift shared by most Persians, and after thousands of years, some sentiments have gone far off the rails. My teeth are itching for you, says the hungry lover or someone simply overcome by cuteness. Does a charming moment really cause itchy teeth in the average sane person? And what does it mean when a person says to you, their expression frustrated and annoyed, Do you want me to put dirt on my head? One of my favorites is the multipurpose insult that I translated roughly as, you dirty corpse washer! The actual expression is simply Corpse washer. But the direct address you connotes aggression in English. And the addition of dirty clarifies the Persian stance on the profession. I modified many of the idioms in my novel this way, making them accessible to an English audience, and for the sake of my own enjoyment. After all, none of these sentiments is new. What makes them lovely is that each is infused with a heap of melodramatic imagery. Lovers with fangs exposed. Mourners with dirt covered heads. Sometimes, I’ve had to add a word here or there to summon in the Western reader’s imagination the expression on a speaker’s face, the gesture of his hands, the flash in his eyes.

Persians never express themselves mildly when melodrama is an option. Phrases likeI am your servant (instead of thank you) or I would die for you (instead of I’m happy to help) pepper everyday language between family, friends, even business partners. This, in turn, affects the authenticity of every interaction. Lying is one of the greatest Persian arts, a skill everyone must have just to make it through a simple social event. The concept of Taarof (polite lying), for example, permeates the culture and comes from these discrepancies between intended meaning and spoken language. That, however, is a whole other topic. Suffice it to say that the literal truth is a slippery thing in Iran, and language is the last place you should go looking for it. You can, however, find a wealth of implication and meaning if you look between the donkeys and the dates, past the uncut watermelons, and into the mullah’s pockets.

Shares