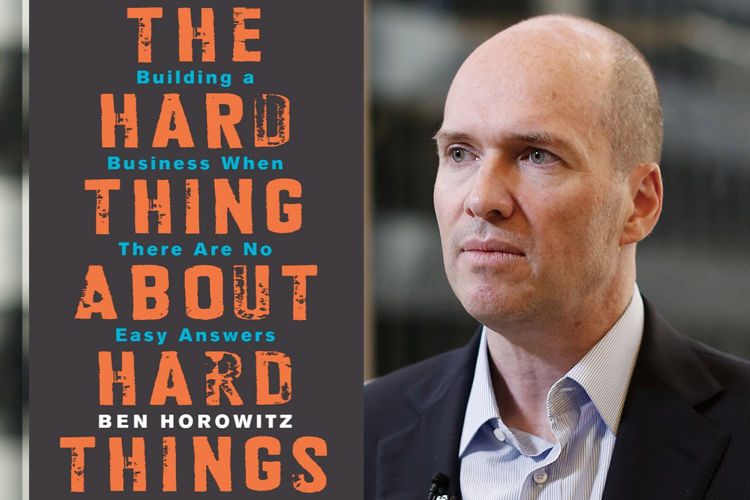

I don’t normally review books on business management. It’s not an area that either I or — I’m just guessing — the typical Salon reader is particularly interested in. But when a PR person representing venture capitalist Ben Horowitz contacted me to see if I was interested in an interview with the author of “The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy Answers,” I jumped at the chance.

Horowitz’s VC firm, Andreessen Horowitz, is at the front lines of the current tech boom, investing in companies both big (Facebook, Twitter, Groupon) and about-to-be-big (AirBnB, Coinbase, Pinterest, Foursquare, Jawbone). Horowitz’s Bay Area tech economy pedigree goes way back — he was an executive at Netscape, which means he was present at the creation of the dot-com boom. He even enjoys the rare honor of having successfully steered a late ’90s startup (LoudCloud/Opsware) through the first crash. In other words, he’s not a newbie.

The grandson of Communists who was raised in Berkeley, a guy who comes by his passion for hip-hop as honestly as any white-boy tech mogul can claim, Ben Horowitz seemed to me like the perfect person to chat with about how the tech economy is — and isn’t — serving the needs of consumers and the wider society.

Of course, it was only fair to read the book and talk a little about the topic of how to be an effective CEO when everything around you is devolving into chaos, but Horowitz didn’t appear to mind when I kept steering the conversation toward larger questions. The tech economy’s impact on society is, as he acknowledged, the topic of the day.

There’s a section in your book called “Preparing to Fire an Executive.” That’s not a situation that most people are ever going to find themselves in. Why did you write this book? Who were you writing it for?

When I was a CEO, the books on management that I read weren’t very much help after the first few months on the job. They were all designed to give you directions on how not to screw up your company. But it doesn’t take long before you get beyond that and you’re like OK I’ve screwed up my company; now what do I do? Most books on management are written by management consultants, and they study successful companies after they’ve succeeded, so they only hear winning stories.

Your book arrives at a time and in a place where the debate about the impact of tech economy wealth on society is extraordinarily heated. Your own company, Andreessen Horowitz, is right in the middle of this, funding the companies that are remaking San Francisco and the world. But your contribution is a book about how to be a CEO during tough times. How does that plug into this larger debate?

I think it has humanized and given some depth and color to what the company-building process is like. Because the terms of this debate have gotten completely cartoonish, both from the detractors and the advocates of the tech economy.

On the advocate side, everybody’s claiming that their company is making the world a profoundly better place. It’s bizarre — when you hear some of these narratives, you’re like, really? That’s making the world better? But then on the detraction side it’s just programmers gone wild and they’re all kids in Ferraris, and that’s not really true either.

I do think we’re in a brave new world. When I started out, technology companies used to sell technology to technology people. You built a disk drive and sold it to a PC company, or you built a computer and you would sell it to a big business. In the last five to ten years, technology companies have become focused on consumers, and the technology has gotten to the point where a software-based company can go in and challenge an existing industry like taxis or hotels.

That’s changed everything. It’s changed the amount of money involved, it’s changed the job-displacement physics, and it has become super-emotionally heated. It’s something that we think about a lot here, trying to understand. It’s definitely a big thing.

You could argue that Netscape started that consumer-facing change, couldn’t you?

That’s right. It was sort of the first one. Now the genie is way out of the bottle.

I’m interested in your perspective on how the industry has changed over time in the Bay Area. In the ’90s, it seemed to me that a lot of the people building the Internet economy were originally geeks and nerds who were kind of surprised to see what they were passionate about suddenly become big business. Now it seems like people are drawn to the tech economy here primarily because they want power and money. It’s a different culture, and it’s rubbing a lot of longtime residents the wrong way.

That actually first happened in 1999 and then it stopped. They all came out here and then they all left because it all turned to crap. So this is the second time I’ve seen it.

One of the things I talk about in the book is having the right kind of ambition. Why people are here is becoming a bigger and bigger question these days. It is hard to build a really big company if you have too many people who take a very self-centric view. If people are there for all the wrong reasons, it can degenerate into a nasty situation.

I do think a lot of people are trying to do important things still, and I think it is really a great thing that entrepreneurship is getting easier. When I started it was just much harder to begin a company. That narrows the scope of what people will attempt and it rules out most people under 30. The bad thing about young people starting a company is that sometimes they do it for the wrong reasons or because they have the wrong skill set, but the good thing is that they don’t have any of the old paradigms baked into them, so they have a lot of the bright new ideas that are harder to come by as you get older.

So what do you tell these youngsters who come to you looking for funding? What’s your most important lesson?

There isn’t one lesson that solves everything. One of the biggest things is to just think for yourself. That is the distinguishing characteristic of the great entrepreneurs. Take Mark Zuckerberg. One key to his success is that he really didn’t listen to people if he thought they were wrong, and that includes his own staff! A lot of building a company is, you really have to think for yourself and you really have to believe in what you believe in and that’s the only way through.

Is there a danger there that that necessary self-confidence turns into entitlement and arrogance?

Yes. There’s no question that there is that danger.

So, 20 years ago, when you were at Netscape and I was downloading each new beta of the Netscape browser the second it was available, I did not anticipate that after 20 years of amazing technological progress, wages would be stagnating and income inequality would be growing and society at large would be increasingly questioning whether, on net, all this innovation was a good thing. You’ve been in the middle of it, you’ve helped create this brave new world. Where do you stand on these larger issues?

Those are good points, but I do think you have to take a global view… In the developed world, what you say is totally true; we’ve got this big income gap and so forth. But one of the things that’s happened since the Internet arrived and helped accelerate the process of globalization that is amazing and positive is the rise of the global middle class. The number of people who have moved into what we would call the middle class up from a dollar a day is just astounding

[Intel CEO] Andy Grove had this great line where they asked him: Is the microprocessor good or bad? and he says, “Well, I don’t think that is the right question. It’s like asking if steel is good or bad. It just is.” Once it is invented it’s there.

I think the Internet is a lot like that. It’s here. Obviously, if we have a globalized world through the Internet, we have to rethink everything from employment to income equality. San Francisco has become this huge lightning rod for this.

One of the things that fascinates me is the difference between San Francisco and Silicon Valley. Because in Silicon Valley, the only culture is the tech culture, but in San Francisco there is a culture and a tech culture and they are not integrated. One simple but very powerful thing that needs to happen in my view is just integrating the two cultures in San Francisco. Tech people need to get more involved, they need to understand the problems they are creating. The complete lack of mixing between the two cultures is a very dangerous thing. And then there is the whole issue of appropriate government policies to deal with these problems. We’re in the pretty early days so I don’t know if I have good answers on that, but it is definitely a big deal. And the changes are not slowing down in the short term.

You start off a lot of the chapters in your book with hip-hop lyrics, and that got me to thinking: In the last 15 years, the percentage of African Americans living in San Francisco has plummeted. What would Public Enemy say about living in San Francisco in 2014?

You know, all the best hip-hop that came out of New York was when New York was a pretty bad city. Now that it has become a much safer place, the hip-hop is not nearly as good. But one of the problems that’s most infuriating to me in San Francisco, and that doesn’t get much attention, is that the restrictions on building are really just there to protect the rich property owners.

If you are rich and you own a house or an apartment building, then you don’t want anybody building any more. But San Francisco is just one-third as dense as Brooklyn, and that’s just crazy. If you just said let’s build it up to Brooklyn’s density you could slow the rise of housing costs for many years.

It is such a logical thing to do, because people who own property aren’t actually adding any value, they aren’t doing any work, they aren’t starting companies, they aren’t creating new jobs. We ought to fix things that can be changed without really hurting anybody, like Proposition 13. Prop 13 should be repealed. I don’t add any value to the world by owning an expensive house, so I ought to pay a high tax on that. That’s the best kind of tax, just paying for being a fat cat, as opposed to taxing someone who is working or trying to build a company, or trying to support their family. There are a lot of stupidly easy obvious policy decisions that could improve things a fair amount.